Red and black: The secretive National Reconnaissance Office finally faces the budgeteersby Dwayne Day

|

| “Hill immediately volunteered that he probably has the poorest working relationship with OMB as anyone in town,” Haynes wrote. |

This secretive existence also required special bureaucratic arrangements. One of these arrangements was that as long as the NRO’s budget stayed below a billion dollars—for comparison, NASA’s budget peaked at over $5 billion in 1965 and declined to a bit over $3 billion by the end of that decade—the budget would be approved by Congress with no oversight or questioning. The NRO budget stayed below that magic number throughout the 1960s, in part via some clever accounting: launch vehicle costs, launch site infrastructure, and some other major program costs like satellite tracking and control, were all charged to the Air Force, not the NRO. In contrast, NASA had to pay for most of these things in its own budget.

But at some point in the early 1970s, the NRO’s budget started to cross that magic number and it began to gain scrutiny, including from the executive branch’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). A newly declassified interview with one of the legendary leaders of the NRO sheds new light on how the NRO came to resent this scrutiny after spending so many years hidden in the shadows. It also reveals how this NRO leader viewed the office’s relationship with other members of the intelligence community during that time.

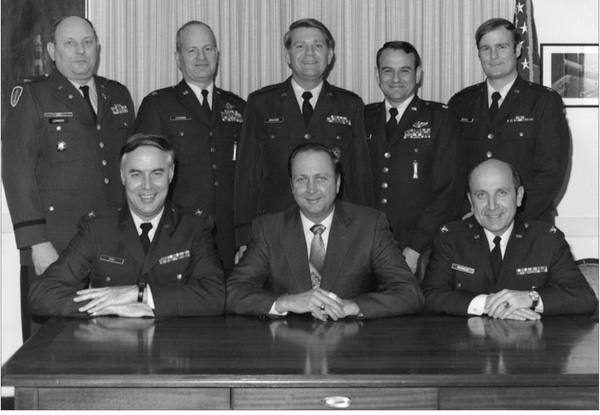

Jimmie Hill was a former Air Force officer who rose up through the civilian ranks of the NRO during the 1970s and 1980s, eventually becoming the long-serving Deputy Director of the National Reconnaissance Office, a position he held from 1982 until 1996. NRO directors came and went, but Hill was always there. He understood the NRO intimately, and as the saying goes, he knew where the skeletons were buried.

In January 1982, only a few months before he became deputy director, Hill sat down for an interview with a person named Haynes, who is otherwise unidentified. Hill was then the Director of the Office of Space Systems, which placed him in charge of the NRO’s Headquarters Staff that oversaw the procurement of new systems. Haynes produced a summary of his interview, not a transcript, so he did not always quote Hill directly. Nevertheless, his summary makes clear that Hill had some strong opinions.

“Hill immediately volunteered that he probably has the poorest working relationship with OMB as anyone in town,” Haynes wrote. This occurred over the past ten years of dealing with the budget office. This “seems to arise from his objection to OMB trying to tell him and his engineers how much it should cost to build a given system.”

Haynes’ interview confirms something that has really only become apparent in the last few years: that a major driver for NRO intelligence collection in the latter 1960s was the Soviet anti-ballistic missile (ABM) threat. (See “Little wizards: Signals intelligence satellites during the Cold War,” The Space Review, August 2, 2021.) That drove two major requirements, for photo-reconnaissance and electronic intelligence. In the late 1950s, concern about Soviet ballistic missiles had driven the development of photo-reconnaissance systems such as CORONA and GAMBIT.

According to Hill, up until 1973 or 1974 OMB (before 1970 known as the Bureau of the Budget) played no part in the development of intelligence requirements. If the NRO’s Executive Committee, or ExCom, which included senior officials from the Department of Defense and CIA, determined that a system was necessary, NRO would then proceed to build it, and the money would simply be approved without much question, either by Congress or the executive branch.

Hill stated that the NRO became a victim of its own success. Because it had run so well up until the early 1970s, the president created the Committee on Foreign Intelligence to run the entire intelligence community in a way like how they ran the NRO. The NRO’s ExCom was no longer in charge of approving NRO programs, and they now had to be considered along with the rest of the intelligence program.

| Historical NRO budgets remain classified to this day, but in the interview, Hill made a rather surprising claim: from 1971 to 1976, the NRO budget went down, not only in inflation-adjusted terms, but in actual dollars. |

“THIS IS WHEN IT WENT TO HELL” Haynes wrote, emphasizing Hill’s annoyance using all-caps. “Instead of looking at 4 to 6 large programs that were relatively easy to understand, they started to look at hundreds of issues.” The NRO’s ExCom had looked at issues at a relatively high level. But now the NRO’s Headquarters Staff, which dealt with the ExCom, and was a team of highly-experienced officials, many of them Air Force officers, had to deal with many different intelligence agency staffs on relatively small issues. Now everybody who had a say in the intelligence program wanted to know what the NRO was doing and why. “The 1974-1977 time frame was the first time that NRO was treated like every other program in the intelligence community,” Haynes wrote. Jimmie Hill considered this a bad thing. Considering that some estimates indicate that the majority of the useful intelligence being collected during the Cold War came from the NRO’s systems, it’s not hard to understand why Hill and others at the NRO believed they were not like every other intelligence agency.

As everybody was putting their nose into NRO’s business, OMB became more involved in questioning the budget. “It is very hard to price out systems that will not be built for 7 or 8 years,” Hill added.

Hill did not mention another reason for increased oversight starting in the mid-1970s: congressional hearings into the intelligence community. These hearings famously exposed CIA covert operations to assassinate Fidel Castro in the Kennedy years. But they also resulted in various efforts to reform the intelligence community and make it more accountable.

Hill thought that Director of Central Intelligence Stansfield Turner was a major problem. He would tell the Secretary of Defense that he would make the final decisions, and if there was a dispute in front of the president, the president would tell OMB to make the decision based on budgetary considerations.

In Hill’s view, OMB had been less of a problem with the fiscal year 1983 budget than it had been during the Carter years, when there had been major disagreement over several programs.

The NRO had relatively little paperwork compared to other DoD programs. According to Hill, for ordinary DoD programs 15% of the cost was in the paperwork compared to only 2% of the cost for NRO programs. This made the NRO much more efficient. But it also meant that OMB could not audit NRO programs as closely as DoD programs. Hill believed that this created distrust at OMB, where officials concluded that because NRO did not have cost overruns, they had too much money. So in fiscal 1982, OMB issued a $35 million across-the-board cut to NRO’s budget.

Hill chafed at OMB second-guessing his engineers about what a satellite system would cost and claimed that OMB had no expertise to second guess his NRO staff. He worried that this would actually cause his staff to cut their estimates to “buy in” and get a system started. But OMB’s emphasis on cost cutting was putting pressure on his people. “OMB can’t initially estimate the cost of a program but claims they can tell within $2 million what it should cost after NRO submits its estimates.”

Historical NRO budgets remain classified to this day, but in the interview, Hill made a rather surprising claim: from 1971 to 1976, the NRO budget went down, not only in inflation-adjusted terms, but in actual dollars. He attributed this to a halt in upgrading existing systems to wait for the development of the space shuttle, which would enable substantial redesign of the systems. “We didn’t have anything for about five years,” Hill said. But between 1979 and 1982 the NRO started to upgrade every major system they had, resulting in a substantial increase in the budget.

As perhaps a sign of how deep down in the weeds OMB had gotten, Hill cited the example of the “DUAL FARRAH” P-989 satellite. The satellites were piggy-backed onboard the HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite and pushed off in orbit to head to their own operating orbits. One FARRAH satellite was already constructed and would be launched in May 1982. According to Hill, both the DoD and the NSA wanted a second satellite, but OMB opposed it. OMB lost the fight, and a second satellite was built and eventually launched in June 1984. What Hill did not state was that the P-989 satellites were the most inexpensive satellites in the NRO’s inventory. They were cheap. If OMB was objecting to buying another one, it meant that OMB was nickel-and-diming the NRO’s budget on everything. However, Hill believed that while OMB was justified in questioning the number of satellites that NRO purchased, it had no expertise to tell them how much they should cost.

| What Hill did not state was that the P-989 satellites were the most inexpensive satellites in the NRO’s inventory. They were cheap. If OMB was objecting to buying another one, it meant that OMB was nickel-and-diming the NRO’s budget on everything. |

Hill cited another issue where OMB had gotten involved, although this one remains confusing. The previous year, the NRO looked at combining two of the low-altitude signals intelligence systems, the P-989 satellites and the Navy’s ocean surveillance satellites. Both collected signals, and proponents for combining them believed that this would be “better technically.” However, combining the systems would have resulted in fewer satellites and would increase the revisit time for the DoD mission—presumably meaning that it would take longer to gather the ocean surveillance data. According to Hill, DoD opposed it for this reason. OMB agreed with DoD, and after deliberations, the DoD approach to keep the systems separate was approved.

Hill’s comments, as paraphrased by Haynes, are somewhat puzzling. A newly produced history of the NRO’s Staff contains an account of the late 1970s low-altitude signals intelligence study that indicates that whereas the CIA pushed for the consolidation, it was not only the Department of Defense that opposed it, but the Director of the NRO as well—Jimmie Hill’s boss. These very limited accounts leave open the question of whether Hill supported or opposed consolidating the systems, or if his primary objection was simply the involvement of the budget office in the decision. However, by the later 1980s the consolidation was eventually approved and the systems were merged.

The interview with Jimmie Hill is just a tiny snapshot of what was happening with the NRO at the time. But it provides insight into how the NRO leadership was chafing at the increased scrutiny the office was receiving. Compared to the first decade of its existence, when the NRO answered to few people, now the secretive organization was being forced to explain its actions to many more actors.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.