Dark Clouds: The secret meteorological satellite program (part 3)The National Reconnaissance Office finally builds top secret weather satellitesby Dwayne A. Day

|

Space Launch Complex 5 as seen circa 2007. The protective shed was pulled to the left, away from the launcher/erector. Note the railroad line along the coast. Some launches were delayed as trains rolled through the base. (credit: Dwayne Day) |

Cloud-reconnaissance vs. photo-reconnaissance

By 1960, the United States had finally begun operating its first photo-reconnaissance satellites under the code-name CORONA. These joint CIA-Air Force satellites took images of the Soviet Union on polyester-based film and returned the film to Earth in reentry vehicles. The first film to return from orbit often had 40-50% cloud cover obscuring the images. Reconnaissance experts warned that as newer, higher-resolution camera systems such as the various Samos satellites and the GAMBIT satellite became operational, cloud cover would become more important because their cameras had smaller fields of view, meaning that even a few clouds could mean the difference between a successful photograph and wasted film.[1]

| If he had to defend the military satellite in an unclassified setting, Charyk might be asked why morning weather imagery of the Soviet Union was so vital that it required a separate satellite. |

Reconnaissance experts had known for many years that cloud cover presented problems for photo-reconnaissance systems, particularly automated systems that could not be controlled by a camera operator. Because of this, they recommended that weather reports be used to better guide reconnaissance so that automated systems did not waste precious film photographing cloud-covered targets. Their concerns were amplified by the early experience with CORONA, and soon the US Air Force began evaluating proposals for a weather satellite to aid photo-reconnaissance operations.[2]

NASA had launched the first spin-stabilized Tiros weather satellite on April 1, 1960, shortly before the first successful CORONA launch. Tiros had started out as an Army satellite before it was transferred to NASA. Although Tiros was an impressive development, it had limited utility for aiding the reconnaissance mission. Its orbit did not reach Moscow and the northern territories of the Soviet Union, and it had other technical limitations. By late 1960, some in the Air Force became interested in a smaller version of Tiros primarily for “cloud reconnaissance” in support of reconnaissance satellites, rather than a dedicated weather satellite. (See: “Dark Clouds: the secret meteorological satellite program, (part 1),” The Space Review, March 28, 2022, and part 2, April 4, 2022.)

The Air Force also had a bureaucratic interest in developing its own weather satellite. By 1961, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Department of Commerce were jointly developing a single National Operational Meteorological Satellite System (NOMSS) to meet all civil and military meteorology requirements.[3] Those who ran the Air Force reconnaissance program were concerned that NOMSS would be unsuitable for reconnaissance purposes.

There were several problems with the joint NASA-Department of Commerce effort. First, NOMSS was not scheduled to be operational until 1963 or 1964, which meant that many important Soviet targets, such as ICBM launchers, might not be photographed in the meantime because of inadequate weather support to the reconnaissance program. Second, Tiros had been a spin-stabilized satellite that only imaged an oblique swath of the Earth. NASA wanted to develop a more advanced satellite for NOMSS that did not rely upon spin-stabilization. This entailed greater risk and could result in delays. Third, NOMSS was an open, civilian program involving sharing data with international partners. Any ties with the secretive reconnaissance satellite program posed multiple risks, including the revelation of classified information, at the very least possibly exposing the covert CORONA reconnaissance satellite program.

The birth of Program II

By late 1960 and early 1961, the Air Force created the Space Systems Division, or SSD, out of the space-related offices in Ballistic Missiles Division in Los Angeles. SSD officials anticipated being named the primary or “executive agent” for space, meaning that they would be in overall charge of all non-intelligence national security spacecraft. In the jargon of the military community, this was a “white” division, meaning that its programs were publicly acknowledged. The Air Force would admit that they existed.

The officers in SSD began work on a “Five Year Space Plan” for the military. As this plan progressed, a modest Scout-boosted meteorology satellite program first proposed in February 1961 was enlarged. The program was widely known as MISS, for Meteorological Information Satellite System, and by late May 1961 the plan was for MISS to consist of 13 launches. But the “Five-Year Space Plan” quickly died in the upper reaches of the Pentagon, apparently because it was too costly and ambitious.[4]

Major General Robert Greer was in charge of the Samos Program Office, which was officially part of the Pentagon’s Office of Missile and Satellite Systems, or OMSS. The Samos Program Office was co-located with SSD in Los Angeles and obtained some office support from it. Unlike Space Systems Division, Greer's office operated in the “black,” meaning that virtually everything that it did was classified. The project office was in charge of such programs as the GAMBIT reconnaissance satellite and the Program 102 signals intelligence satellites. Whereas the white part of SSD reported through a military chain of command—various generals all the way up to the Chief of Staff of the Air Force—Greer’s office reported directly to a sole Air Force civilian in the Pentagon, Undersecretary of the Air Force Dr. Joseph Charyk. He was a technically trained and highly-respected civilian who had recently been given direct line of authority over the Air Force’s intelligence satellite programs.

Joseph V. Charyk, the first Director of the National Reconnaissance Office. Charyk approved the development of the top secret weather satellite program in July 1961. (credit: NRO) |

On June 21, after Charyk was briefed on several of the space systems in the Five Year Space Plan, he quietly instructed General Greer to put together a “minimum” proposal involving a four-vehicle meteorological satellite program instead of the 13-satellite program. This order removed the meteorological satellite program from the regular Air Force and Space Systems Division and transferred it to his authority.[5]

Five days later, Greer approved the “minimum plan” produced by his people and sent it to Charyk. On July 11, Charyk submitted it to the new Director of Defense Research and Engineering, Harold Brown at the Pentagon, with a request for both approval and funding.[6] Charyk thought that the program should provide global weather information during the 1962–1963 period when NASA's follow-on to the Tiros satellite would still be in pre-flight development.[7] After that point, Charyk figured, the advanced Tiros system would probably take over. In the meantime, a highly classified military system would not attract attention from Congress.

| Major decisions in the white Air Force space bureaucracy required multiple committee meetings and reviews. In contrast, in the black space program there were fewer standardized regulations, more power in the hands of individual project managers, and a chain of command that was very clear. |

There was a key reason why Charyk and others did not want to have to publicly justify a separate military weather satellite: in order to support photo-reconnaissance operations over the Soviet Union, the weather satellite would have to fly over the Soviet Union in daytime, particularly the morning, before a reconnaissance satellite would fly over the same area. In contrast, the civilian weather satellite overflew the United States during the daytime. If he had to defend the military satellite in an unclassified setting, Charyk might be asked why morning weather imagery of the Soviet Union was so vital that it required a separate satellite. He did not want to say anything publicly that raised the issue of the highly secret reconnaissance program.

On July 12, 1961, after the proposal was sent to Brown, Charyk instructed Greer to change the security of the proposal from conventional “secret” to “Mandatory Knowledge.” This meant that only personnel who absolutely needed to know about the project would be made aware of it, and most of those who already knew of it would be cut off from information about it. He also directed that all program information would only be transmitted by a sealed envelope system and suggested changing normal Air Force documentation processes to restrict access.

Finally, Charyk asked that they consider changing the name of the project. MISS was already known by too many people.[8] By July 15, Harold Brown advised Charyk that he would support the “minimum program” if it could be clearly demonstrated that the system had advantages over an expanded Tiros development.

Charyk convinced Brown during a conversation on July 19, and that day he telephoned Greer that Brown had approved the proposal.[9] These moves transferred control of the military meteorological satellite program from the “white” world of the regular Air Force space bureaucracy to the “black” world. The rules in this world were completely different. Major decisions in the white Air Force space bureaucracy required multiple committee meetings and reviews. Standard procurement regulations had to be followed. Each decision had to be reported up through several levels of bureaucracy. In contrast, in the black space program there were fewer standardized regulations, more power in the hands of individual project managers, and a chain of command that was very clear, with a direct line to Charyk. Now the project was approved and Greer had to find somebody to run it.[10]

Greer placed Lieutenant Colonel Thomas O. Haig in charge of the program. Haig was a meteorologist and electrical engineer by training. He took over the program in late July 1961. Haig selected a small team to work on managing the various aspects of the effort: booster, satellite, ground station, etc. He insisted that the project be a “blue suit” operation, meaning managed by Air Force officers and not civilians. One condition of him taking over the project was that he would not have to use the Aerospace Corporation to provide systems engineering, as the non-profit company was doing for many Air Force space programs. Haig had a dim view of Aerospace, which he thought had already become attached to too many satellite programs. Haig also believed that the project was so small and streamlined that outside support was not necessary and uniformed Air Force officers (and a few civilians) could oversee the technical management of the program. Haig was also told that if the first launch could not be done on schedule or if the costs were likely to exceed the fixed budget, Haig was to cancel the program and recover government funds. This gave him leverage when dealing with the satellite contractor.[11]

Lieutenant Colonel Tom Haig ran the top secret Program 417 weather satellite program from 1961 to 1965. Haig kept the program office small and tried to keep the costs low. The program eventually evolved into the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program, which still has satellites operating today. (credit: NRO) |

Greer and Haig agreed to temporarily designate the project “Program II.”[12] At the time, the Samos Program Office’s primary effort was a new high-resolution satellite then called “Program I” and later designated the KH-7 GAMBIT. For security purposes, the Program II office was physically located outside of the Samos office, although it received its money from a classified budget. This unusual bureaucratic arrangement kept the tiny weather satellite office isolated, so that its work could not be connected to the reconnaissance program and its members would not be exposed to the reconnaissance work.

A simple satellite

Haig negotiated a fixed-price contract—meaning that both contractor and government agreed on an overall price before starting—with the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). Because RCA already built Tiros, and the classified satellite was a simpler, smaller version of Tiros, the fixed-price contract was appropriate.

RCA was to develop a 45-kilogram (100-pound) satellite shaped like a ten-sided polyhedron. It would be 53.3 centimeters (21 inches) high and 58.4 centimeters (23 inches) across and spin-stabilized—smaller than Tiros, although using some of its major components. Whereas Tiros had two wide-angle cameras, the military satellite would have only one. The spin would be induced by small solid-propellant rockets. The satellite would actually be spun at a higher rate for stability during its injection into orbit. Once it was in orbit, it would deploy small weights on the ends of wires to slow its rotation down before the wires were ejected. The satellite would be placed in an 833.4-kilometer (450-nautical-mile) circular Sun-synchronous orbit.[13]

There were several differences between the military meteorological satellite and NASA’s Tiros satellite besides its size. For starters, Tiros was just heavy enough to require a Thor-Delta booster. The Program II satellite was lighter and could fly aboard the smaller Scout. Thor-Delta was a NASA rocket not in the Air Force inventory. Scout was also a NASA rocket, not an Air Force one, and Haig was never happy with the contract arrangements for purchasing the rocket.

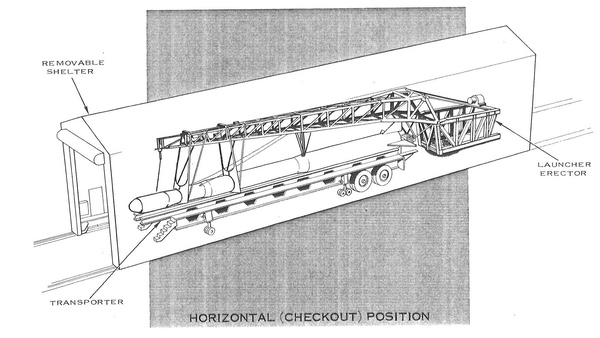

The mechanism for holding the Scout rocket in place and erecting it vertically. The Scout was controlled by NASA and had major reliability problems in the early 1960s, resulting in the loss of several Program 417 weather satellites. This prompted the program manager to secure different boosters for the vital payloads. (credit: USAF) |

Although Tiros was also spin-stabilized, it was oriented with its bottom toward the Earth, spinning like a top, because NASA engineers did not know how else to stabilize it as it moved through the Earth’s magnetic field. Its cameras stuck out of the bottom of the satellite off-axis, which meant that they imaged oblique views of the Earth. The Program II satellite, in contrast, would rotate with its long axis pointed in the direction of flight. Its single camera was mounted along the radius of the satellite so that each time it swept over the face of the Earth, it imaged a swath of ground (and clouds) below. The camera was turned on and off by horizon sensors. RCA estimated the sensor system would have an orbital life of 90 days—hence, four satellites launched successively would theoretically provide one year of coverage.[14]

| The first operational P-35 satellite was also used during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, proving its value for aerial reconnaissance missions conducted by U-2 and tactical fighter jets as well as satellites. |

Another difference compared to Tiros was that an electrical loop was fixed around the satellite’s perimeter. An electrical current could be passed through this loop to generate toque against the Earth’s magnetic field to maintain the satellite perpendicular to the orbital plane—this was the innovation that enabled the satellite to roll along in its orbit instead of spin like Tiros. The imagery over the Eurasian landmass would be tape-recorded and relayed to ground stations in the United States.[15]

Finally, a key difference between the Program II satellite and Tiros was that the military satellite had no redundancy, no backup systems. If a primary system failed, the entire satellite would fail. The managers chose this approach to keep both weight and cost to a minimum.

In September the name of the program was officially changed from Program II to Program 35, which the Air Force officers often abbreviated as “P-35” in conversation and paperwork.[16] It never received a code-name. By this time, the Department of Defense had also created the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) with Charyk as its first director. Charyk still maintained his unclassified title as Undersecretary of the Air Force, but the NRO was so secret that even its name was classified, never to be spoken outside of a secure facility.

RCA engineers developed the P-35 satellite quickly and encountered only a single hitch: the failure of a model during a vibration test. The metal base plate of the model, upon which all the electronics rested, cracked unexpectedly. RCA engineers wanted three months to fix the problem, but after Haig told them they had only ten days or he would cancel the contract, they quickly returned in three days with a proposed fix and a revised schedule. They still managed to meet the original ten-month schedule.[17]

The first Program 417 launch (then known as Program 35) from Space Launch Complex 5 at Vandenberg Air Force Base on May 23, 1962. The payload splashed down offshore. (credit: NRO) |

First launch

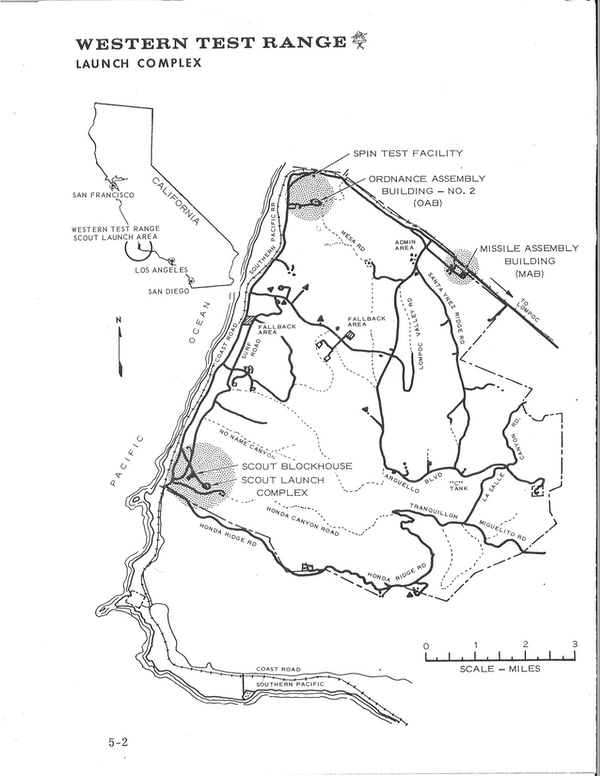

A test launch of a Scout rocket from Slick-5 at Point Arguello Launch Complex at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on April 25, 1962 failed, dropping a classified Navy GRAB signals intelligence satellite into the water.[18] Although those developing and building the P-35 satellites were concerned about this failure, the following month they affixed their first satellite to a Scout at Vandenberg. On May 23, the launch crew fired the Scout with the first P-35 aboard over the Pacific Ocean. It did not go far before a Scout malfunction caused it to splash down within sight of the launch facility.

In July 1962, the satellite program was redesignated “Program 694BH.”[19] This was a temporary bureaucratic designation by the Air Force, which was busy applying odd designations to various space programs.

The early Program 35/Program 417 satellites launched atop Scout rockets at Vandenberg. The Scout and payload were integrated inside a launch shed. The shed was then pulled away and the rocket was erected on its arm, ready to launch. (credit: USAF) |

The second satellite launch, lifting off from Slick-5 on August 23, was successful, placing its satellite into a useful orbit. The satellite soon returned weather imagery to a ground station in New Hampshire. Each vidicon image produced a picture of a 1,482-kilometer (800-mile) square area of the surface below, recording it on tape as an analog signal for later transmission to the ground. The imagery was relayed by cable from the ground stations to the Air Weather Service’s Air Force Global Weather Central at Strategic Air Command (SAC) Headquarters at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska. The information was then relayed from Global Weather Central to the ground stations used to control the CORONA satellites, and operators then decided whether to allow the CORONA satellite’s camera to take its pre-programmed photography, or to hold off for a better opportunity. If the target was important enough, ground controllers generally chose to take the picture anyway and hope that they got lucky and managed to shoot through a hole in the clouds.

The first operational P-35 satellite was also used during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, proving its value for aerial reconnaissance missions conducted by U-2 and tactical fighter jets as well as satellites. The cloud cover imagery enabled mission planning for the reconnaissance flights and also reduced the number of aerial weather-reconnaissance sorties in the region. The satellite finally ceased transmitting on March 23, 1963—seven months in orbit as opposed to its three-month design life.

Soon after the August 1962 launch, the program received its fourth and final name change. It was redesignated Program 417 and this name lasted for the remainder of the decade.

| Five launches with only one complete success convinced Haig that the Scout was too unreliable and he canceled the remaining order for two more launches as well as a follow-on Scout order. |

By fall of 1962, it was clear to everyone involved in the military weather satellite program that the civilian NOMSS, which was growing in complexity, was going to be delayed and the “interim” military weather satellite might have to operate for a longer period than originally planned. Joseph Charyk told Haig to prepare to operate the Program 417 satellites for another year. Haig had already planned for this and drafted a contract for four more satellites.

After receiving an expensive proposal from Lockheed for developing new ground stations, Haig proposed establishing two ground stations under Air Force control located in Maine and Washington state, at either end of the country. Haig’s plan used existing Nike surface-to-air missile sites as well as leftover equipment taken from other programs. It was another example of Haig’s thrifty approach to the program. Charyk approved the plans and secured a meeting with Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay, who liked the idea of Air Force officers—particularly from Strategic Air Command—directly operating the satellites. LeMay gave Haig his full support.[20]

Program 417 launch on February 19, 1963. This satellite was placed in an improper orbit. (credit: NRO) |

The third launch took place on February 19, 1963. Unfortunately, the Scout placed the satellite in an improper orbit, rendering it useless for weather observations for all but a few months—after May it was not useful except for engineering tests. This satellite also carried an infrared radiometer for measuring the amount of nighttime cloud cover. The radiometer proved to be successful and Haig decided to have it installed as regular equipment for future Program 417 satellites. This began a long-standing policy of introducing new and experimental weather sensors to the program.

Two more launches from Slick-5, on April 26 and September 27, 1963, also ended in Scout booster failures. Five launches with only one complete success convinced Haig that the Scout was too unreliable and he canceled the remaining order for two more launches as well as a follow-on Scout order.

Space Launch Complex 5 at Vandenberg was located not very far from the Pacific Ocean. Occasionally, Air Force personnel watched the rockets lift off from SLC-5 and then splash down offshore. (credit: USAF) |

Switching to Thor

Haig had already decided to try to obtain spare Thor Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles returned from England and Turkey. He and his team fitted a Thor with a solid-propellant rocket motor they nicknamed “Burner I.” But before this new rocket combination was ready, the group also acquired two more powerful Thor-Agena rockets. The Thor-Agenas were capable of launching two Program 417 satellites at once.[21]

On January 19 and June 17, 1964, the Air Force launched Thor-Agena D rockets from Vandenberg each carrying two Program 417 satellites into orbit. This restored the meteorological satellite system, which had suffered a gap since May 1963, when the only operational satellite had stopped transmitting.[22]

The decision to use converted Thor ballistic missiles as launch vehicles led to an agreement by December 1963 to have Strategic Air Command crews launch the satellites from Vandenberg. Thus, SAC was gaining responsibility for both launching and operating the weather satellites in addition to processing the imagery. The SAC-launched satellites would lift off from Space Launch Complex-10—“Slick-10”—located very close to where the CORONA satellites that they supported launched into orbit.

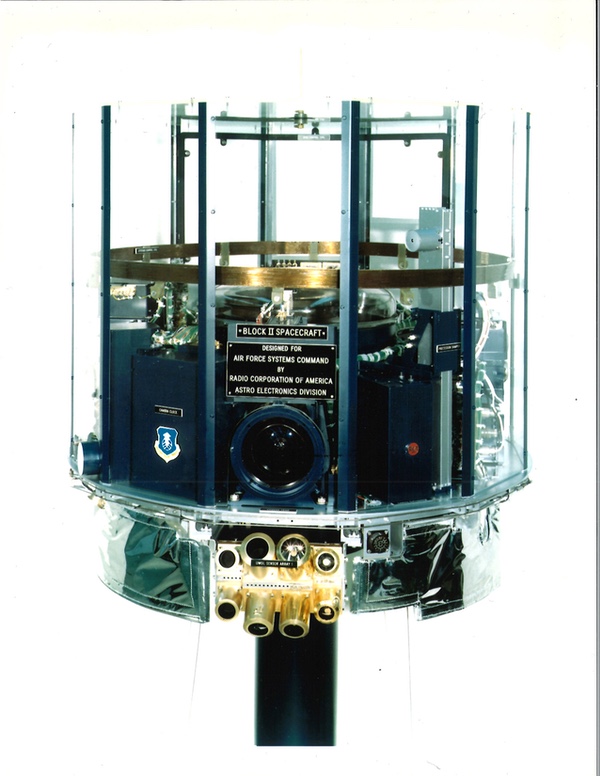

Up to this point, all the satellites launched were designated Block 1 (spelled using Roman numerals, i.e. “Block I”). During 1964, the 417 program office began working on modifying three additional satellites. These satellites weighed 73 kilograms (160 pounds), carried two improved infrared radiometers, and were equipped to transmit directly to the smaller ground terminals in Maine and Washington. They were designated Block 2 (“Block II”).

A mockup of the Block 2 (“Block II”) version of the satellite. (credit: NRO) |

Despite the launches of multiple satellites expressly developed to improve photo-reconnaissance operations, in 1963–1964 CORONA reconnaissance satellites were still only producing 50–60% cloud-free photographs, not any better than before the Program 417 satellites entered service. According to an official history of the program, this was at first partly due to meteorologists at the NRO’s Satellite Operations Center in the Pentagon failing to properly define cloud cover “in terms of the relative viewing angle to the target.” A further problem was in the terminology used by different communities involved in the operations for designating locations. Eventually, intelligence customers submitted imagery target requests based upon a single standard, enabling those processing the weather satellite imagery to determine if a specific area of the Earth was cloud-covered or free. Later in the decade, “the Air Weather Service's Air Force Global Weather Central began work on a three-dimensional cloud analysis,” according to NRO historian Cargill Hall.

The Program 417 satellites were used to provide data shortly before reconnaissance satellites overflew their targets, but they also contributed to a much better understanding of when and where clouds were expected over targets of interest. “The programs merged all overhead imaging and civilian weather reports into a global cloud analysis with a spatial resolution of 25 nautical miles on a polar stereographic grid, by date and time of day. By the late 1960s, employing a software program devised by the Air Weather Service, Air Force Global Weather Central could estimate the probability of cloud-free access on any day and time throughout the year for any required target.”[23]

A CORONA reconnaissance satellite prepared for launch in spring 1964. CORONA photographs often had 50% cloud cover. The weather satellites were intended to provide data about clouds over the targets, allowing controllers to cancel photographic passes and conserve film. (credit: Peter Hunter Collection) |

Tactical applications

The Program 417 satellites were designed and operated for the specific mission of supporting reconnaissance satellites. This meant that they recorded their imagery while over the Soviet Union and then transmitted that imagery to the ground when over the United States. The satellites did not have the ability to simultaneously take and transmit imagery over the United States or many other parts of the world, which limited their utility for tactical military users. For American military forces deployed to Germany, the United Kingdom, South Korea, and many other places, the satellites were of no real use, and weather observations were still often made by sending aircraft out to record atmospheric conditions.

By 1963, NASA’s NOMSS satellite, also known as Nimbus, was behind schedule. In addition to its mission supporting civilian weather users, NOMSS was intended to provide weather support to Department of Defense tactical forces. In January 1963, Harold Brown, the Director of Defense Research and Engineering, asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff if NOMSS would meet the DoD’s tactical requirements. The JCS indicated that it would not, and recommended that the DoD build its own direct-readout weather satellite to relay day-and-night tactical meteorological data to transportable ground and shipboard terminals.[24]

An example of clouds over a CORONA reconnaissance target in the Soviet Union. Despite the development of the Program 417 satellites, in 1963–1964 CORONA missions still returned with up to half their photographs marred by cloud cover. This was due to poor coordination within the Air Force and National Reconnaissance Office over how to determine cloud cover. Eventually, this was corrected and reconnaissance satellite operators were better able to determine when to take their photos. (credit: NRO) |

| Initially developed as a “cloud reconnaissance” satellite to support photographic reconnaissance operations, it had demonstrated its utility for tactical military operations. The support of forces in Vietnam impressed many in the military who became aware of it. |

The JCS recommendation for a separate military weather satellite was not possible given the existing political and bureaucratic situation, and NOMSS would remain the planned solution to meet military meteorological satellite requirements. However, the NRO and the Defense Department approved a test of a Program 417 satellite to support tactical forces. This occurred during exercises at Fort Leonard Wood in southwest Missouri in 1964. Air Force Global Weather Central at Offutt Air Force Base sent weather pictures directly to Air Force and Army users supporting the exercises, as well as for fighter aircraft deploying for a flight across the Atlantic.[25]

In November, Global Weather Central provided tactical weather data over Central Africa to Military Airlift Command. The data was crucial for an operation to airlift Belgian paratroopers to Stanleyville in the Congo, where they were involved in the freeing of hostages who had been seized during an uprising.[26]

Both exercises demonstrated the value of a weather satellite to tactical operations. But the tactical users wanted surface resolution better than the 5.6 kilometers (three nautical miles) provided by the existing satellites. They also needed direct delivery to local ground stations where the data could be evaluated by meteorologists attached to the units.

Meanwhile, starting in fall 1964, local weather forecasting for US forces in Southeast Asia was hindered by degraded data when the communist government in Hanoi stopped broadcasting local weather reports. The Defense Department sought help from the NRO and, in March 1965, a Program 417 satellite was launched that could provide noontime data to support tactical operations in Vietnam. Colonel Haig planned and laid out a ground station at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon, South Vietnam. Within 30 minutes of receipt of data, the station provided complete cloud-cover data for North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and parts of Laos, China, and the Gulf of Tonkin.[27]

Soon additional mobile, air-transportable ground terminals were installed at Osan Airbase, South Korea, and Udorn Airbase, Thailand. A fixed site was also installed at Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii.

The program had undergone an important transition during 1964. Initially developed as a “cloud reconnaissance” satellite to support photographic reconnaissance operations, it had demonstrated its utility for tactical military operations. The support of forces in Vietnam impressed many in the military who became aware of it.

On January 18, 1965, the Air Force launched a Thor-Burner I rocket with a Block 1 satellite from Space Launch Complex 10 at Vandenberg. During ascent the payload shroud failed to separate and the extra weight caused the satellite to reenter. Fortunately, sufficient spares were in orbit that this was no longer a major blow to the overall program and the next launch, in March, was successful. By this time, two Sun-synchronous weather satellites were operating in their circular orbits, with one satellite passing over the Soviet Union at about 0700 local time and another following at about 1100 local time. In October 1965, a single satellite was launched that was specially equipped to transmit to the smaller tactical terminal deployed to Vietnam. It was designated Block 3 (Block III) to distinguish it from the satellites that solely supported the strategic reconnaissance mission.

Following the March 1965 launch, one Block 3 and three Block 2 satellites had been launched over a 12-month period. Although created as an “interim” program until NASA’s more advanced weather satellite became available, Program 417 had been extended by several years and demonstrated that a military weather satellite could be both useful and reliable, serving both strategic and tactical users. The satellites provided the National Reconnaissance Office daily strategic observations of cloud distribution and organization over Europe and Asia.

In June 1965, NRO Director Brockway McMillan informed the incoming Air Force Chief of Staff General John P. McConnell that the military weather satellite program was being transferred from the NRO to the USAF effective July 1. The Los Angeles program office would move from the NRO to the Space Systems Division located next door—the SSD was where the proposal for a smaller version of Tiros, the Meteorological Information Satellite System, had first emerged in February 1961.[28]

The Program 417 classification level was reduced, but its origins in the secretive NRO were not revealed until decades later. Although designed for “cloud reconnaissance,” the satellites had significantly impressed the Department of Defense, and “weather reconnaissance” from space became an important support function for the US Air Force. Unfortunately, the weather satellite program did not always run smoothly under Air Force control.

Next: Part 4, the Air Force gets its weather satellite.

Program 417 launches

| Date | Launch Vehicle | Payload | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 23, 1962 | Scout SLC-5 | Block I | Failure | Second stage exploded |

| August 23, 1962 | Scout SLC-5 | Block I | Success | |

| February 19, 1963 | Scout SLC-5 | Block I | Partial success | Improper orbit |

| April 26, 1963 | Scout SLC-5 | Block I | Failure | Third stage exploded |

| September 27, 1963 | Scout SLC-5 | Block I | Failure | Third stage failure |

| January 19, 1964 | Thor-Agena D SLC-1W | 2 Block I satellites | Success | |

| June 17, 1964 | Thor-Agena D SLC-1W | 2 Block I satellites | Success | |

| January 18, 1965 | Thor-Burner I SLC-10W | Block I | Failure | Payload shroud did not separate |

| March 18, 1965 | Thor-Burner I SLC-10W | Block I | Success | |

| May 20, 1965 | Thor-Burner I SLC-10W | Block III | Success | |

| September 9, 1965 | Thor-Burner I SLC-10W | Block II | Success | |

| July 1, 1966 | Thor-Burner I SLC-10W | Block II | Failure | Upper stage failed to ignite |

| March 30, 1966 | Thor-Burner I SLC-10W | Block II | Success |

Endnotes

- For more information on the early reconnaissance satellite development, see Dwayne A. Day et. al., Eye in the Sky (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998). Note: Both “Samos” and “GAMBIT” were often capitalized in official documents in the 1960s. However, over time, the capitalization of the names became less consistent.

- Weather satellites had been evaluated by the Air Force alongside reconnaissance satellites for years. See: S.M. Greenfield and W.W. Kellogg, "Inquiry Into the Feasibility of Weather Reconnaissance From a Satellite Vehicle," R-218, The RAND Corporation, April 1951. For info on the effect of cloud cover on reconnaissance, see: W.R. Cartheuser, "Weather Degradation of Reconnaissance," D-4003, The RAND Corporation, 10 December 1956.

- John H. Ashby, "A Preliminary History of the Evolution of the Tiros Weather Satellite Program, (HHN-45)," NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center, August 1964, NASA History Division.

- Robert Perry, A History of Satellite Reconnaissance, Volume II, “Program 417 Weather Satellite Program,” p. 214; 210-211.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 212.

- Ibid., p. 231.

- Ibid.

- R. Cargill Hall, “A History of the Military Polar Orbiting Meteorological Satellite Program,” National Reconnaissance Office, September 2001, pp. 1-10.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Tom Haig e-mail to Dwayne A. Day, February 8, 1999.

- Ibid.

- "Program 417 Weather Satellite Program," pp. 223-224.

- Tom Haig e-mail to Dwayne A. Day, February 8, 1999.

- Tom Haig fax transmission to Dwayne Day, September 22, 1998, p. 1.

- “A History of the Military Polar Orbiting Meteorological Satellite Program,” p. 4.

- Point Arguello Launch Complex was merged with Vandenberg Air Force Base in 1964. Technically, all launches from there before the merger are not Vandenberg launches.

- Ibid.

- Tom Haig e-mail to Dwayne A. Day, February 8, 1999.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “A History of the Military Polar Orbiting Meteorological Satellite Program,” pp. 30-31.

- “Ibid., p. 12.

- Ibid., p. 13.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 14.

- Ibid., p. 15.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.