Commercial space stations: labs or hotels?by Jeff Foust

|

| “The difference between animals and humankind is culture,” said Giron. “We wanted to be able to celebrate conviviality in space.” |

It was at that event that Maison Mumm announced a partnership with commercial spaceflight company Axiom Space to fly its champagne into space. That partnership was more than just grabbing a bottle of Mumm and sticking it in the cargo hold on a future Axiom mission. Instead, Mumm worked with a design firm and the French space agency CNES to develop a special bottle, featuring aerospace-grade aluminum and a “perfectly reliable stainless steel opening-closing mechanism” that complies with both spaceflight safety regulations and those governing champagne in France. The champagne itself, Mumm Cordon Rouge Stellar, is a special blend developed for this project, featuring “notes of ripe yellow fruit and vine peach, but also dried fruit, hazelnut and praline,” the company said.

At the event, with terrestrial Mumm champagne flowing freely from traditional bottles, officials with Maison Mumm, Axiom, and others talked up the partnership. But why go through all the effort to send champagne to space? For César Giron, president of Maison Mumm, it was inevitable. “The difference between animals and humankind is culture,” he declared, pointing out Mumm champagne was part of the first French expedition to Antarctica in 1904. “We wanted to be able to celebrate conviviality in space.”

“Life is about experiences. It is about culture. It is about enjoying yourself in various ways,” said Michael Suffredini, CEO of Axiom Space.

So when will the champagne fly in space? “It’s our intent to fly it on our next flight,” Suffredini said, referring to the Ax-2 mission the company plans to fly to the International Space Station next spring. “We’ve got some work to do to sort that out.”

Flying the champagne, though, isn’t the same as drinking it. Consumption of alcohol is not allowed, at least on the US segment of the ISS. “Well, one of the things that Axiom is known for is kind of pushing the limits a little bit with the government,” he said. “We’ll take it a step at a time. We’ll fly the bottle and then talk about how we’ll do our testing.” He added he didn’t think the company would have to wait until it starts adding its modules to the ISS around the middle of the decade to, ah, test the champagne.

Axiom Space CEO Michael Suffredini (center) speaks about his partnership with Maison Mumm to fly its champagne on future Axiom missions. (credit: Maison Mumm) |

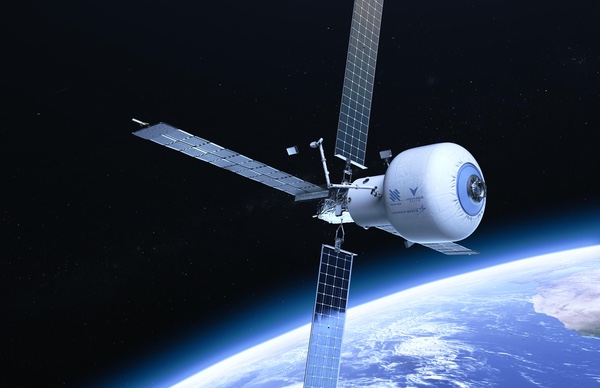

The Mumm-Axiom partnership was not the only announcement the week of the conference dealing with commercial space stations and hospitality. A day earlier, Voyager Space announced it would work with Hilton on its Starlab commercial space station concept. Hilton will be the “official hotel partner” for the station, helping design accommodations on the station. The companies will also work together on “the ground-to-space astronaut experience” and other tourism-related efforts.

The announcement brought back memories of Barron Hilton’s proposals in the 1960s for a “Lunar Hilton” and the cameo a Hilton Hotel on a rotating space station played in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The press release about the partnership mentioned Hilton’s “storied history with space” but, curiously, linked instead to a project less than three years ago when Hilton’s DoubleTree chain flew, and baked, cookies on the ISS.

But the conference and associated events illustrated a dichotomy regarding marketing of commercial space stations. On the one hand, the stations are being touted as destinations for tourists, with accommodations by Hilton and champagne by Mumm. The same companies, though, are also emphasizing those stations as destinations for research and opportunities for countries, not wealthy individuals, to live and work in space.

| “It is very, very important not to break it, because that is the last thing you want to break on the station,” said Kavandi of the toilet. “You do not want that to break.” |

Voyager, for example, announced signing memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with five Latin American space agencies and organizations to study flying payloads on Starlab and helping plan use for the station and its George Washington Carver Science Park. That science park will have a terrestrial component that the company announced will be established at the Ohio State University, starting in an agricultural engineering building and later moving to its own building at the university’s Aerospace and Air Transportation Campus.

Axiom Space, meanwhile, used the conference to announce several agreements to fly people or payloads. Perhaps the biggest was the announcement of a deal with the Saudi Space Commission, Saudi Arabia’s space agency, to fly two Saudi astronauts on a future Axiom mission. The two astronauts would fly next year, the Saudi Space Commission said, but did not disclose how they would be selected other than that one of them would be a woman.

Axiom also provided few details about flying the Saudi astronauts amid speculation they could go on next spring’s Ax-2 mission; the company has not announced who will take two of the four seats on that Crew Dragon mission to the ISS. “This partnership highlights Axiom Space’s profound commitment to expand human spaceflight opportunities to a larger share of the international community, as well as to multiply scientific and technological development on Earth and in orbit,” Axiom CEO Suffredini said in a statement.

The Saudi agreement was one of several Axiom announced during the conference. It signed an agreement with the government of Turkey to send the first Turkish astronaut to space on a future Axiom mission, and announced MOUs with Canada and New Zealand for research activities; the agreement with the Canadian Space Agency also opened the door to flying Canadian astronauts on Axiom missions. In July, Axiom signed an MOU with Hungary to study opportunities such as flying a Hungarian astronaut.

Orbital Reef, the commercial space station project led by Blue Origin and Sierra Space, also seems to be straddling the research and tourism markets. During a session of the IAC, Janet Kavandi, president of Sierra Space, discussed the importance of having a staff of professional astronauts running the station, taking care of the day-to-day maintenance of the facility. “We’re going to have people that have to maintain the space station so that the people that are up there doing that incredible stem cell research, the biological research,” she said, “don’t need to be bothered with the toilet, or the IT system when it goes down.”

But the companies are also thinking about what’s needed for the station to support tourism. Kavandi cautioned not to compare Orbital Reef with a five-star terrestrial resort. “It’s going to be a little bit different in space,” she said, because there will be a smaller staff. “Part of the training that I have in mind is to limit expectations, but also to realize that what you’re going to get for that experience is more than you can imagine.”

Those differences between Orbital Reef and a terrestrial hotel extend to the bathroom, which will be “rudimentary” in space. “It is very, very important not to break it, because that is the last thing you want to break on the station. You do not want that to break.”

“I am very keen as a community to develop food as an experience,” said Brent Sherwood, senior vice president of advanced development programs at Blue Origin, at the session. Tourists, he suggested, might want to “eat like astronauts” for one day of their stay. “But for the other days, I think we need to learn how to actually cook in space. And nobody knows how to do that.”

The effort by companies proposing commercial space stations to balance tourism and research may in part be good public relations. Millionaires flying to space is a big target for criticism of wasteful spending. Even Axiom’s partnership with Mumm to fly champagne to space generated pushback: “Space tourism hits a new low,” tweeted Michael Byers, co-director of the Outer Space Institute at the University of British Columbia, in response to the announcement.

| “It’s unclear if the market can support four competitors, or two competitors. We don’t know, really,” said Dittmar. |

Developing commercial space stations to support work like biomedical research, though, is easier to build support for. The same may be true for giving more countries opportunities to send people into space, although that may come with geopolitical complications. (It will be interesting to see if that happens with the Saudi astronauts; at IAC, a bid by the Saudi government to host the 2025 IAC in Riyadh that appeared to be the frontrunner encountered a backlash from International Astronautical Federation members, who instead selected Sydney, Australia.)

Another reason may be more practical: companies just aren’t sure where the demand will be for commercial space stations, beyond NASA’s stated interest in transitioning research currently done on the ISS to such stations, and are covering their bases to be ready to support research or tourism as they emerge.

During one panel discussion at IAC, an Axiom executive offered a cautionary note. “I think we’re going to have to be really hard-headed about business cases, and I don’t think we’re there at all,” said Mary Lynne Dittmar, chief government and external relations officer at Axiom Space.

Just how much demand there is for research, tourism, or other applications is uncertain, she said. “It’s unclear if the market can support four competitors, or two competitors. We don’t know, really.”

NASA is currently supporting four teams—Axiom, Blue Origin/Sierra Space, Northrop Grumman and Voyager—for commercial space station studies or, in Axiom’s case, access to an ISS port for attaching commercial modules. Few, though, think that all four will be able to follow through, technically and fiscally, on their station concepts.

“There’s going to be some hard choices that need to be made,” Dittmar said of narrowing down the field of space station companies, “and they will need to be made sooner than most people are prepared to make them.”

Some, though, hold out hope that all four can continue. “I hope there’s enough of a market for all of us to succeed,” said Andrei Mitran, director of strategy and business development at Northrop Grumman, during another IAC session. “We are looking at how do we make the pie bigger,” he added. “Otherwise we could kill this market.”

So, perhaps, by the end of the decade tourists on a commercial space station might be sipping their Mumm champagne from specially designed glasses while floating by a window, watching the Earth below. On the other hand, it might be researchers who are breaking out the bubbly to celebrate a milestone in a research project on a commercial station. In either case, where people go, champagne will follow.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.