What the United States should do regarding space leadership?by Namrata Goswami

|

| Cold War-dictated concepts like technology demonstration and prestige missions to showcase ideological superiority, funded by billions of dollars of taxpayer money, cannot sustain space investments in this changing world. |

One look at Japan’s basic space law and policy of 2008 shows that the language used about space is focused on space development and utilization, specifically as it aims to develop Japanese citizens’ capacity to earn economic returns from Japan’s space development. For Japan, it states, “Space Development and Use shall be carried out in order to strengthen the technical capabilities and international competitiveness of the space industry and other industries of Japan, thereby contributing to the advancement of the industries of Japan, by the positive and systematic promotion of Space Development and Use as well as smooth privatization of the results of the research and development with regard to Space Development and Use.” Japan pointed out that cooperation with the United States is critical in this regard.

This is in an interesting shift in language and narrative, as the space economy grows and becomes an integral part of an individual, and by extension, a community’s life. Cold War-dictated concepts like technology demonstration and prestige missions to showcase ideological superiority, funded by billions of dollars of taxpayer money, cannot sustain space investments in this changing world. A country has to justify their space missions based on economic return. We witnessed this reality when the Indian Minister of State (Independent Charge) for Science and Technology and Earth Sciences, Jitendra Singh, had to rationalize money spent on India’s human spaceflight program as aimed at building space tourism, specifically by promoting the participation of the private space sector through the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorization (IN-SPACe) agency. IN-SPACe is a new agency established under the Indian Department of Space to promote and authorize the Indian private sector activities in space. A country like China, known for the dominance of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in regard to its space programs, issued direction in 2014 for the development of China’s private space sector—of course, in tight coordination with its state-sponsored civilian space and military institutions—to develop space capacities like reusable rockets, satellite constellations, and commercial spaceports.

In this context of a fast-changing space environment, assuming global leadership in space through establishing norms and standards of behavior—a rules-based regime in space—by a group of democratic nations, is vital. The US remains, by far, the leading nation in space but that lead is fast shrinking with China’s emergence as a spacepower in the 21st century, enhanced with the strategic partnership that China has established with Russia. China under President Xi Jinping has articulated grand strategic ambitions of assuming leadership in key strategic technologies, including space.

| The framework misses the boat on where partner nations want to go: space development and use, space tourism, and space as an industrial activity. |

Wu Yansheng, Chairman of China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC), outlined China’s ambitions in space in an interview on China Central Television-CCTV December 20. Those ambitions follow a strategic plan of the CPC to turn China into a comprehensive spacepower in the next two decades Writing the rules of the road, determining the space economy and space governance mechanisms, and underwriting the space development of other nations through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Spatial Information Corridor are key components of China’s plans for space development and space utilization.

US Space Priorities Framework

Under the Biden Administration, the US released its Space Priorities Framework in December 2021 that focused on how space activities enhance our lives by offering satellite communications, data, help address the climate crisis, and how “space exploration and scientific discovery attracts people from across America and around the world to engage in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).” Space was projected as a mystery in the document that exploration missions will help unlock, and that “the United States will maintain its leadership in space exploration and space science.” The Priorities Framework indicated that “the United States will advance the development and use of space-based Earth observation capabilities that support action on climate change”. Regulations that the Biden Administration aspires to promote are those that enable a commercial space sector focused on traditional space goals like space applications and space-enabled services.

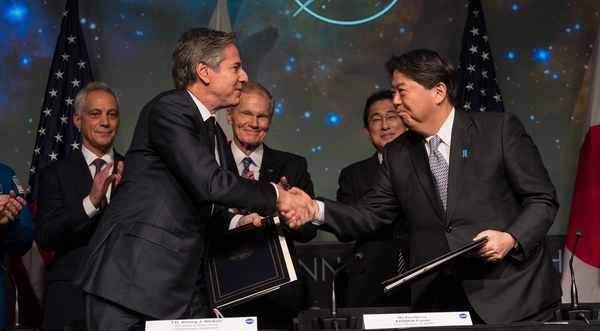

All these are laudable space goals, but the framework misses the boat on where partner nations want to go: space development and use, space tourism, and space as an industrial activity. Japan just licensed the first business activity on the Moon when it granted the first space mining license to ispace supported by its space mining legislation that also establishes ownership of those resources. Consequently, US partner nations are taking leadership and organizing to deal with challenges like China. For example, Japan took the initiative towards creating frameworks like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue that includes space cooperation among Japan, the US, Australia, and India.

While the US Space Priorities Framework is a good document and touches upon all the usual issues like space science, space exploration, space leadership, and does recognize space as part of US critical infrastructure (if not critical infrastructure itself), it completely fails to recognize the changing global landscape of the space narrative focused on space development and utilization. The document asserts US space leadership while failing to provide how that leadership is being developed in the 21st century and is unclear as to which key space domains and technologies (low Earth orbit, cislunar space, in-space manufacturing, renewable energy, etc.) are the key focus of the Biden Administration. The document does not provide strong enough strategic rationales for why other nations should accept this US leadership in space at all, and why it is important for the US to maintain that leadership in a world where authoritarianism is on the rise.

What should the US do, then, to maintain space leadership and ensure that the future in space is democratic, inclusive, and representative, and is indeed enabling democratic societies to commercially benefit from space development and utilization?

Recommendations for US actions

It is critical that the United States charts a policy direction in space that recognizes this critical component of space development and space utilization for communications, commerce, trade, navigation, military capability, space resource utilization, and business activity in cislunar space. What the United States particularly needs to accomplish is to ensure that this leadership position in space that the Cold War offered the United States remains a key strategic advantage in the 21st century.

For this key strategic advantage to continue, the United States needs to ensure five vital things in space.

| The US space vision should offer a compelling vision of the economic development of space that other nations and their societies can relate to. |

First, the US should recognize and connect space development and space utilization to its grand strategic vision of who it is in the 21st century, especially after the end of the Cold War, particularly to promote democratic development of space, and for free commerce to flourish. This implies that a 21st century US space priorities framework, instead of starting with the most obvious goals of “leadership in space exploration and space science,” should instead state that the United States will maintain leadership in space to enable the democratic development of space, and that it will accomplish these with like-minded partner nations. Such democratic space developments will include harnessing renewable energy in space like space-based solar power (SBSP) that will help tackle climate change, development of the Moon as an industrial hub enabled by responsible regulation, and the use of space for national security purposes to ensure access to space remains free and open.

Second, while Earth observation capabilities are critical means to the end of understanding Earth and preserving our planet, they are not an Apollo-like mission that galvanized an entire generation. Unfortunately, the Artemis lunar mission is not Apollo either, and in its current form not aimed at long-term development of the Moon for economic purposes. China’s Chang’e missions, with long-term goals of permanent settlement of the Moon and the utilization of space resources like helium-3 and water ice is galvanizing the Chinese population to support China’s space development and is drawing in members of the BRI. The US needs to make the Artemis program not only more sustainable in the long run but also have bolder visions of lunar development that follows Japan’s cutting-edge space innovations in mining regulation and space policy.

Leadership in cislunar space is key in setting the right narrative for democratic development of space, and not just limited to Earth orbits like LEO and GEO. The Moon is the focus of spacefaring nations and societies across the world. The US needs to set the right narrative and the vision that others can be inspired by, and that vision for lunar development should spur a movement for responsible development of the Moon. The US does not have such a narrative yet, but should build one that is suitable for 21st century space. Human beings are moved by grand visions that they can relate to and feel included in. The time is ripe for such a US grand strategic narrative for space. Perhaps President Biden can offer such a vision of space development.

Third, committing resources to space development is extremely important. By resources, I mean stable long-term financing and joint ventures, such as, for example, a joint venture between the US and Japan or other members of the Quad on SBSP or lunar development for resource utilization. That would be a gamechanger, something innovative and inspiring. If successful, it will have the potential to change the world energy situation. At a minimum, it will galvanize innovation, jobs, and scientific spinoffs that space has provided for so many other industries in our lifetime. Such funding commitments can only happen with a clear space vision of development and utilization.

Fourth, the US should commit to truly democratize space, moving the space discourse from elites to larger societies across the world, something like what has happened with the Internet, which evolved from a small network for researchers funded by the Defense Department in 1969. A similar trajectory can be charted in space, as we shift space travel from an elite activity today with only few of us fortunate enough to be state-chosen astronauts or with millions of dollars to afford a seat to get to space—to the point that we idolize the few astronauts today—to enabling millions of us to access space and turning space into a normal activity. If US leadership in space can accomplish such a feat, that will be a true inspiration to humanity.

Finally, space is economic power. China recognizes that, Japan recognizes that, and so do several other nations. From the Chinese grand strategic perspective, a nation can only build its influence if it emerges as the top economic power. Once that is accomplished, military power and diplomatic power is going to follow. Space is perceived and sold as building China’s economic power. What is important to realize is that even China’s lunar program is marketed as an investment program that could bring about $10 trillion annually within the framework of an Earth-Moon Economic Zone by 2050.

The US continues to perceive space as a prestige issue, projecting future achievements like landing humans again on the Moon as grand achievements similar to Cold War narratives while the rest of the world has moved on from “space as prestige” to “space as economic and military power.” Grand visions are critical to garner long-term support, both from domestic constituencies but also from the world at large. The US space vision should offer a compelling vision of the economic development of space that other nations and their societies can relate to. Such grand visions worked during the Cold War, in weaving together the idea of free societies versus the Soviet Union model of controlled societies. It is therefore important from a grand strategic perspective that the US, with its multiethnic, multicultural society (despite its difficulties), truly symbolizes democratic representation and freedom, and is therefore the best option we have to lead the future space international order.

In conclusion, the United States should take leadership and develop a clear vision of space development and use. Only such a grand strategic visioning will galvanize society and create an enormous inspirational conversation about what the United States can do for humanity in space.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.