Not-so ancient astronauts and Area 51: the Skylab Incidentby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The CIA considered no other spot on Earth to be as sensitive as Groom Lake, and NASA astronauts had just taken a picture of it. |

Groom Lake isn’t really a lake. Or at least it’s not usually a lake. It is a dry lakebed, far out in the Nevada desert, miles from prying eyes. It is a secret Air Force facility that has been known by numerous names over the years. It has been called Paradise Ranch, Watertown Strip, Area 51, Dreamland… and Groom Lake. Groom is probably the most mythologized real location that few people have ever seen. For people with overactive imaginations, it is where the United States government keeps dead aliens, clones them, and reverse-engineers their spacecraft. It is also where NASA filmed the faked Moon landings. So Groom Lake is not only not usually a lake, it is for many people a magical location, a Shangri La in the Nevada wastelands.

However, for humans whose feet rest on firmer ground, Groom is the site of highly secret aircraft development. It is where the U-2 spyplane, the Mach 3 Blackbird, and the F-117 stealth fighter were all developed and/or tested. It has also probably hosted its own fleet of captured, stolen, or clandestinely acquired Soviet and Russian aircraft. Because of this, the United States government has gone to extraordinary lengths to preserve the area’s secrecy and to prevent people from seeing it.

The CIA considered no other spot on Earth to be as sensitive as Groom Lake, and NASA astronauts had just taken a picture of it.

The Skylab 4 crew was the third and last crew to visit the orbiting space station. (credit: NASA) |

Shutterbugs

The third and last Skylab crew had launched into space on November 16, 1973, as part of the Skylab 4 mission. Onboard were three rookie astronauts: Gerald Carr, Edward Gibson, and William Pogue. Carr was a Navy commander, Pogue was in the Air Force and had flown for their elite Thunderbirds team, and Gibson was a scientist-astronaut with a doctorate in engineering physics.

The crew quickly fell behind schedule early in their mission for several reasons, but soon regained time. They repaired an antenna, fixed problems with the Apollo Telescope Mount and an errant gyroscope, and replenished supplies. They accumulated significant EVA time and studied the sun for over 338 hours.

The three astronauts of Skylab 4 were Gerald P. Carr, Edward G. Gibson, and William R. Pogue. Their mission lasted 84 days. (credit: NASA) |

They also took photographs of the Earth, including a photo of the secretive Groom Lake facility in Nevada. On February 4, 1974, after a record 84 days in space, they splashed down 280 kilometers southwest of San Diego. They were recovered aboard the USS New Orleans and found to be in excellent shape.

NASA had an agreement with the US intelligence community that dated from the beginning of the Gemini program: All astronaut photographs of the Earth would first be reviewed by the National Photographic Interpretation Center in Building 213 in the Washington, DC Navy Yard. NPIC (pronounced “en-pick”) was an organization managed by the CIA that interpreted satellite and aerial photography. At first, the photo-interpreters had wanted to see what astronauts could contribute to reconnaissance photography. During the Gemini program they discovered the answer: not much. The photographs returned during the Gemini missions had many problems, including lack of data on what the camera was pointed at. There was no good way for an astronaut to record the precise time and pointing angle of a camera when he took a picture, and so the interpreters often had a very difficult time determining what they were looking at.

But there was another reason to evaluate the astronaut photographs: to see if they showed anything interesting, or anything that they should not, like a top-secret airstrip in the middle of nowhere.

Spooky actions at a distance

There was a certain irony in NPIC photo-interpreters discovering photographs of Groom Lake, because even within NPIC’s highly-secure Building 213, Groom Lake was classified. Images of Groom were removed from rolls of spy satellite film and stored in a restrictive vault. As a former senior NPIC official explained, “there were a lot more things going on at Groom than the U-2.” Not all the photo-interpreters at NPIC were cleared to know about these things, but they included aircraft testing of advanced reconnaissance drones and captured Soviet fighter planes. The average photo-interpreter might know that the U-2 and the Blackbird had been tested at Groom, but would be surprised to see a B-52 with drones, or a MiG-21 sitting on its runway. Soviet MiGs were evaluated and flown at Area 51 starting in the late 1960s, and it is possible that they were present at the base when the Skylab astronauts took their photo.

| Why the Skylab 4 astronauts disobeyed their orders and took the photo is unknown. |

In fact, in April 1962 a CIA official suggested to his superior that they consider taking pictures of Area 51 using their own reconnaissance platforms. John McMahon, the executive officer of the abstractly named Development Plans Division, wrote the acting chief of DPD: “John Parangosky and I have previously discussed the advisability of having a U-2 take photographs of Area 51 and, without advising the photographic interpreters of what the target is, ask them to determine what type of activity is being conducted at the site photographed.” He continued: “In connection with the upcoming CORONA shots, it might be advisable to cut in a pass crossing the Nevada Test Site to see what we ourselves could learn from satellite reconnaissance of the Area. This coupled with coverage from the Deuce [U-2] and subsequent photographic interpretation would give us a fair idea of what deductions and conclusions could be made by the Soviets should Sputnik 13 have a reconnaissance capability.”

Whether or not CIA ever undertook such an exercise remains unknown, but CORONA spacecraft did photograph Area 51 at least a handful of times, so there was opportunity to do such an analysis.

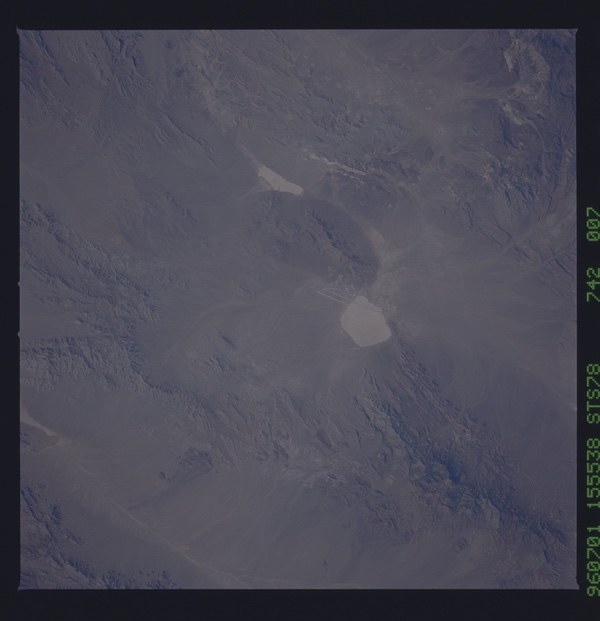

At the time the Skylab photo was being debated within the US government, intelligence officials were apparently unaware that a US Geological Survey photo of Groom Lake had been taken in 1968 and was publicly available, although not public. (credit: USGS) |

The controversy

Why the Skylab 4 astronauts disobeyed their orders and took the photo is unknown. Because they had only handheld cameras for earth observation, the resolution of the image was low. The existence of the base was not a secret, particularly to an Air Force pilot like Bill Pogue—the pilots who flew in the huge Nellis testing range in Nevada referred to Area 51 as “the box” because they were under explicit instructions to not fly into that airspace. But for whatever reason, they had taken the photo and now it had created a stir within the intelligence community.

The April 1974 CIA memo explained the current dilemma government officials were facing over the Skylab crew’s action: “This photo has been going through an interagency reviewing process aimed at a decision on how it should be handled,” the unnamed CIA official wrote. “There is no agreement. DoD elements (USAF, NRO, JCS, ISA) all believe it should be withheld from public release. NASA, and to a large degree State, has taken the position that it should be released—that is, allowed to go into the Sioux National Repository and to let nature take its course.”

What the memo indicates is that there was a difference between the way the civilian agencies of the US government and the military agencies looked at their roles. NASA had ties to the military, but it was clearly a civilian agency. And although the reasons why NASA officials felt that the photo should be released are unknown, the most likely explanation is that NASA officials did not feel that the civilian agency should conceal any of its activities. Many of NASA’s relations with other organizations and foreign governments were based on the assumption that NASA did not engage in spying and did not conceal its activities.

The CIA memo writer added, “There are some complicated precedents which, in fairness, should be reviewed before a final decision.” These included “A question of whether anything photographed in the United States can be classified if the platform is unclassified; Such complex issues in the UN concerning United States policies toward imagery from space” and “the question of whether the photograph can be withheld without leaking.”

The space shuttle crew of STS-78, orbiting the Earth in 1996, also photographed Groom Lake. (credit: NASA) |

Secret as an onion

A cover note to the memorandum, written by the Director of Central Intelligence William Colby himself, stated that “I confessed some question over need to protect since: 1-USSR has it from own sats. 2-What really does it reveal? 3-If exposed don’t we just say classified USAF work is done there?”

Colby’s questions were unusual given the debates that have raged within the US intelligence community for decades over the need for secrecy. Those within the intelligence community who have asked “what is the harm in acknowledging the obvious?” have almost always lost the argument, and the obvious remained classified.

| Groom Lake has been a more ambiguous case. The US government has at times acknowledged and at other times refused to acknowledge its existence. |

Government officials have frequently argued over the need to refuse to confirm even the most basic knowledge about things that have been widely reported in the press for decades. For instance, the existence of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), which manages America’s spy satellite program, first became known in a 1971 New York Times article (a decade after the NRO was created), but arguments flared up within intelligence circles for the next 20 years over whether or not to confirm its existence. Finally, in September 1992 the “fact of” the existence of the NRO was revealed in a terse press release that never even used the word “satellite.” Even after that decision, for several years the NRO refused to confirm that it actually launched satellites on rockets, another glaringly obvious fact.

Groom Lake has been a more ambiguous case. The US government has at times acknowledged and at other times refused to acknowledge its existence. Author Peter Merlin wrote a detailed chronology of all the times the US government publicly acknowledged the existence of a facility at Groom Lake. (See: “It’s No Secret – Area 51 was Never Classified.”) The existence of an airstrip at Groom was revealed when it was first constructed. But at other times the government refused to acknowledge the facility’s existence, only to later confirm it. In 1998, the US Air Force issued a terse statement acknowledging that the facility did indeed exist, even though photos taken on the ground and overhead had been available for decades. In fact, at least two US Geological Survey aerial photographs of Groom taken in 1959 and 1968 had been available in public archives, but not discovered until many years later. In 2013 there were widespread reports that for “the first time,” the US government was acknowledging activities there, despite all the other times it had already done so. The distinction was that for the first time the government had acknowledged a specific activity at the facility—the testing of the U-2 spyplane—as opposed to simply admitting a facility existed.

There is some logic to the secrecy policy of refusing to confirm the “fact of” an organization, or even an airbase in the Nevada desert. Intelligence officials often refer to secrecy being like an onion, and each layer that is peeled off reveals a little more of what is contained within. Even if the next layer is visible in vague form, the advocates of strong secrecy want to keep all the layers in place.

This policy is usually given solid form in legal discussions within government agencies. There the concern is not so much with foreign intelligence agencies, but with American citizens and the press, and their ability to request the declassification of government documents through the Freedom of Information Act. By refusing to even acknowledge the existence of something, government agencies have erected an outer legal barrier against requests for information from their own citizens. Author M. Todd Bennett addresses this subject in the context of the Glomar Explorer case in his new book Neither Confirm Nor Deny – How the Glomar Mission Concealed the CIA From Transparency. The Glomar incident also occurred in 1974, and the CIA—still under the leadership of Colby—erected a substantial policy barrier to protect its secret operations only a short time after Colby seemed to take a more relaxed position in regards to the Skylab photograph. (For more, see: Jeffrey T. Richelson, “Intelligence Secrets and Unauthorized Disclosures: Confronting Some Fundamental Issues,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 2012; and Jeffrey T. Richelson, “Back to Black,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2001.)

A new book by M. Todd Bennett delves into how the CIA erected higher barriers to secrecy starting in 1974, the same year that the agency debated over the release of the NASA photograph of Groom Lake. |

But critics of excessive government secrecy argue that such policies are often pursued unnecessarily, since no law requires the government to reveal anything further about a facility such as Groom after acknowledging its existence. The onion analogy holds validity, but can also be taken too far; after all, the Soviet Union was an extremely secret society and classified things such as road maps, something that had never been classified in the United States.

| Although there are no declassified documents indicating how this dilemma was resolved, it seems like NASA, the State Department—and apparently Director of Central Intelligence Colby—got their way. |

Secrecy critics also argue that there is something wrong when America’s adversaries have better information about the federal government’s actions than its own citizens. Groom Lake had obviously been photographed numerous times by Soviet spy satellites at high resolution before the Skylab astronauts took their low-resolution photo. Refusing to release a single fuzzy photograph from a Skylab mission was taking an abstract ideal—maintaining all the layers of the onion—to an absurd extreme. These critics also argue that when the government fails to confirm the obvious, it both undermines governmental authority and legitimacy, and contributes to wild speculation, such as aliens and soundstages in underground hangars at Area 51. And despite the best efforts, information will still seep out. After all, while various agencies of the federal government were arguing over whether or not to put this low-resolution photograph in an unclassified government archive, nobody realized that several other higher-resolution images were already sitting in that archive, awaiting discovery.

Although there are no declassified documents indicating how this dilemma was resolved, it seems like NASA, the State Department—and apparently Director of Central Intelligence Colby—got their way. The photo was released to a government archive and went unnoticed for several more decades. Ironically, the earlier USGS photos were publicly revealed first. Two decades later, during STS-78, a space shuttle crew would also photograph Groom. But whether or not that caused concern within the intelligence community is unknown. Or at least still classified.

Groom Lake was photographed by Europe's Sentinel spacecraft in 2022. (credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.