The hard truths of NASA’s planetary programby Jeff Foust

|

| “There is a large imbalance today between the workload and the available resources at JPL,” Young said last fall. |

“That is a volcano that has erupted on the surface of Venus,” said Robbie Herrick of the University of Alaska Fairbanks at a press conference about the discovery. The eruption, he said, would likely be like those of Hawaii’s Kilauea and similar volcanoes in Iceland, with fountains of lava that, thanks to the higher surface temperature on Venus, would be runnier than their terrestrial counterparts.

The discovery is not a slam dunk: it required careful analysis of low-resolution radar images taken from different angles, leaving open the possibility of alternate explanations for the differences in the imagery. However, he and another researcher involved in the work, Scott Hensley of JPL, noted two future missions will carry radar instruments that will offer much higher resolution imagery. “The whole Venus community can’t wait to get their hands on these data,” Hensley said.

For one mission, though, scientists will have to wait, if they even get the data at all. While ESA’s EnVision mission is moving ahead for a launch in the early 2030s, NASA’s VERITAS is in trouble. That mission—whose name is an acronym for Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy—was one of two Venus missions selected by NASA in the most recent round of the Discovery program of relatively low-cost planetary science missions in 2021 (see “Venus is hot again”, The Space Review, June 7, 2021).

VERITAS was scheduled to launch in the late 2020s, but in November NASA announced, to the surprise of many, that it would delay the mission by at least three years through no fault of VERITAS itself. Instead, problems with another Discovery mission caused the delay, while broader budget issues, highlighted by NASA’s fiscal year 2024 budget proposal released last week, prompted new doubts about when, or if, VERITAS might launch.

The Psyche spacecraft was supposed to launch last year, but software testing problems delayed its launch to October. (credit: NASA/Ben Smegelsky) |

Psyche-d out

The delay of VERITAS started last year with problems encountered by another Discovery-class mission, Psyche. That spacecraft, going to the metallic main-belt asteroid of the same name, was scheduled to launch in August 2022. However, in May NASA announced that testing of the spacecraft’s software had fallen behind schedule, pushing the launch to a backup launch window in October. By late June, it was clear the mission would not make that window, and NASA stood down from a 2022 launch.

The proximate cause of that delay, the software testing issue, is now in hand, and NASA has rescheduled Psyche for an October 2023 launch. The agency, though, commissioned an independent review to better understand what went wrong with Psyche to prevent something like that from happening again.

That independent review, chaired by the venerable Tom Young, completed its work last fall and NASA discussed them at an online town hall meeting in early November, shortly after announcing the new launch plans for Psyche. That independent review found serious institutional issues at JPL, the lead center for Psyche.

“There is a large imbalance today between the workload and the available resources at JPL,” Young said at that town hall meeting. “This imbalance was clearly a root cause of the Psyche issues and, in our judgement, adversely affects all flight project activity at JPL.”

| “This postponement can offset both the workforce imbalance for at least those three years and provide some of the increased funding that will be required to continue Psyche towards that 2023 launch,” Glaze said of the VERITAS delay. |

The review highlighted several problems, from the lab struggling to retain engineers who can find more lucrative jobs in the private sector to poor communications within project management and among team members, exacerbated by remote or hybrid work since the start of the pandemic. One example included in the report was a JPL Christmas party in late 2021 that was the first time that many team members had met in person since the pandemic; they “exchanged valuable project information” during the party.

Both NASA headquarters and JPL said they were committed to addressing the problems outlined in the report, but the agency was clearly concerned that JPL was overextended. In addition to operating many ongoing missions, it is leading two of the largest planetary missions in development, Europa Clipper and Mars Sample Return. Something had to give.

That something was VERITAS, which was also led by JPL. The agency announced at the town hall meeting that it was postponing the launch of VERITAS from 2028 to no earlier than 2031. “This postponement can offset both the workforce imbalance for at least those three years and provide some of the increased funding that will be required to continue Psyche towards that 2023 launch,” Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, said at the time.

That did not go over well with the Venus science community in general, and VERITAS project leaders in particular, who felt they were being punished for the sins of others. “To this point, we have been on schedule and on budget, and we have an excellent and highly experienced team,” Suzanne Smrekar of JPL, principal investigator for VERITAS, said at an advisory group meeting a few days after NASA announced the delay.

Delaying VERITAS, she argued, created problems for the mission’s European partners providing instruments. It also meant that it would fly around the same time as EnVision instead of going earlier and helping plan the activities of that European mission.

Smrekar said she hoped to find a way to at least shorten the delay. “We understand there are very big hurdles to doing this,” she said, “but we will try to find a way.”

Tough choices

The next sign of problems for VERITAS came last week with the release of the agency’s fiscal year 2024 budget proposal. NASA requested $27.2 billion overall, a 7% increase, largely going to existing science and human spaceflight programs.

Venus scientists, though, greeted the entry in the budget proposal for VERITAS with dismay. NASA requested only $1.5 million for the mission, enough to keep its science team intact but little else. Moreover, the proposal’s future “outyears” projections kept VERITAS at $1.5 million through 2028.

“That’s functionally a soft cancellation,” said Casey Dreier, chief of space policy at The Planetary Society, of VERITAS during a webinar about the budget proposal organized by the Aerospace Industries Association (AIA) last Thursday.

During a NASA town hall meeting at LPSC a day after the release of the full budget proposal, Glaze said the future of VERITAS depended on three factors. One was to secure the funding needed for the mission. She said the project would provide her a proposed budget this spring to support planning for the agency’s 2025 budget proposal, the earliest NASA would consider restarting the mission.

A second factor is progress by JPL in implementing the recommendations of the independent review board. An interim assessment, she said, was scheduled for later this month, with a final one next year.

| “This mission that was on track is being effectively martyred for all those missions that are going over budget,” Smrekar said. |

At a meeting last month of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG), Laurie Leshin, director of JPL, said the lab was seeing signs of progress. More people were working on-site, addressing the report’s concerns about remote work. Some JPL engineers who left for private industry had since come back, she added. “Those hiring and retention issues have really subsided.”

The third factor, Glaze said at LPSC, was getting two other JPL-led missions launched: Europa Clipper and NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR), an Earth science mission that is a joint project with India’s space agency. Europa Clipper is on schedule for a launch in October 2024 while NISAR is slated to launch by early next year; JPL recently shipped the radar mapping payload to India to be integrated onto a spacecraft for launch there.

That last factor puzzled some scientists at the meeting: why should a Venus mission depend on an Earth science project? “It’s not just money. It’s the capabilities and the resource availability at JPL,” Glaze responded. Delays in either mission would keep JPL from freeing up personnel and facilities needed for other projects, including VERITAS.

There was criticism from others at LPSC about the delay to VERITAS. A German scientist involved with the mission noted his budget to help contribute an instrument for it was now larger than for VERITAS itself, and he worried that the delays would result in higher costs for his contribution.

Smrekar, the principal investigator for VERITAS, also weighed in. “This mission that was on track is being effectively martyred for all those missions that are going over budget,” she said. “The reason that so many in the community are outraged by this are these facts, that a mission that was on track is contingent on Earth science missions and all kinds of things that have nothing to do with us.”

“I appreciate your comments. Thank you,” Glaze responded, then went on to the next question at the town hall.

There is still the question, though, of whether NASA can afford VERITAS—or, at least, both VERITAS and the next Discovery-class mission. The budget proposal calls for holding the next competition to select one or two such missions as soon as fiscal year 2025. But NASA has reached out to the planetary science community recently, asking them whether they thought should NASA continue with VERITAS or hold a competition for a future mission.

That came up during the MEPAG meeting last month. Among those who weighed in was Bruce Banerdt, principal investigator for the just-concluded InSight Mars lander, also a Discovery-class mission. “It would be very upsetting to miss the Discovery call, but if they’re implying that they would defund VERITAS in order to fund the Discovery call, that’s even less acceptable,” he said, a view endorsed by others at the meeting.

Glaze suggested at the LPSC town hall that she got similar comments from others. “I’ve asked the community to provide feedback on priorities related to the next Discovery calls and support of the selected mission, VERITAS,” she said. “We’ve got a lot of great support from the community to restart VERITAS, even if that means not holding the next Discovery call.”

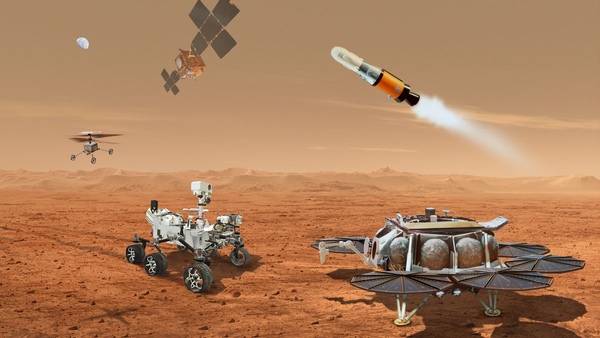

NASA’s fiscal year 2024 budget request warned that costs for Mars Sample Return were growing, which could affect other missions. (credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech) |

Planetary versus heliophysics

VERITAS is caught in a bigger challenge facing NASA’s planetary science portfolio: the agency is trying to do two flagship missions at once. Europa Clipper has an estimated cost of $5 billion and is making progress towards its October 2024 launch. Mars Sample Return (MSR), meanwhile, is seeing its budget grow as it prepares for launches in 2027 and 2028 to return samples by 2033.

NASA’s 2024 budget proposal requested nearly $950 million for Mars Sample Return, up from $822 million in 2023. However, the agency warned that the future projections in spending on MSR were subject to change: “Mars Sample Return costs are expected to increase beyond what is shown in the outyear profile in this budget.” NASA would either have to descope, or scale back, MSR itself, or seek the funding from other science missions.

How much of an increase is possible is not clear, and NASA has not even offered an estimated cost for MSR. At a separate town hall meeting during LPSC last week, agency officials praised the progress they were making on the overall effort, including the cache of samples placed on the Martian surface by the Perseverance rover that could be retrieved if the rover is unable to meet up with the MSR lander and hand over the samples it has collected, including new ones to be gathered in the next several years.

“To me, it is just super exciting that we are at a point now where we are literally within about ten years from bringing samples back from Mars,” said Meenakshi Wadhwa, MSR principal scientist.

| “I think it’s a relatively brittle budget,” Dreier said of the overall NASA budget proposal. |

But how much it will cost to bring those samples back is something NASA has yet to disclose. At the town hall, Jeff Gramling, MSR director at NASA headquarters, said the agency was working through a series of preliminary design reviews that will culminate in one for the entire MSR effort in September. That will be followed, as soon as October, by a confirmation review also known as Key Decision Point C, where NASA makes formal cost and schedule estimates for a project.

He declined to even give a “ballpark” estimate for the cost when asked during the town hall. “I don’t think I’m in a position right now to give you cost data because we’re still working it through our processes,” he said, citing the ongoing efforts to develop “grassroots” cost estimates that will also be checked by an independent review this summer.

It's clear, though, that MSR current costs and projected, if uncertain, cost increases are weighing down the science budget. NASA cited MSR, along with Europa Clipper and Psyche, as reasons for delaying VERITAS in the budget proposal.

Those issues extend beyond planetary science and its proposed $3.38 billion budget. The budget proposal revealed plans by NASA to halt work on a major heliophysics mission, the Geospace Dynamics Constellation (GDC). It would launch six satellites into Earth orbit to study the interaction of the upper atmosphere with the magnetosphere and solar activity, and was a major recommendation of the last heliophysics decadal survey.

“The Budget proposes to pause GDC development, as continuing development would have required a significant increase in funding at a time when other space science missions, such as the Mars Sample Return mission, also have high budgetary requirements,” the agency said in the budget proposal. It requested just $10 million for the project in 2024, compared to a projection of $49.4 million for 2024 in last year’s budget.

Heliophysics spending overall, a small part of the overall $8.26 billion science budget, was cut in the 2024 request to $750.9 million from $805 million in 2023. That might face pushback in the Senate, experts noted. The chair of the Senate appropriation subcommittee is Sen. Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire; the University of New Hampshire hosts significant heliophysics research.

“It is not smart to do things like cut the thing that you think is the chair’s highest priority,” said Jean Toal Eisen, vice president of corporate strategy at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy and a former Senate appropriations staffer, at the AIA budget webinar. “They’re just going to put that back in and take the money from something that you cared about.”

A brittle budget

Congress has yet to weigh in on the proposed budget and issues like cuts to science missions. Shaheen’s subcommittee has tentatively scheduled a hearing on the NASA budget proposal in mid-April, while her House counterparts have not announced a schedule for a similar budget hearing.

“I think it’s a relatively brittle budget,” Dreier said of the overall NASA budget proposal. While many praised the 7% increase proposed for NASA, that only roughly keeps pace with inflation even as spending is projected to go up on many programs not just in science but also for Artemis as NASA gears up for a human return to the Moon later this decade.

“If any one of these programs, or Artemis itself, really goes astray in terms of blowing its schedule or budget, you’re going to see some serious downstream consequences within the agency,” he warned.

At the LPSC press conference about the Venus volcanism discovery, Glaze reiterated her support for VERITAS despite the delay and the budget concerns. The flat $1.5 million a year budget, she explained, was just a placeholder: “We’re waiting to work with the project to get an appropriate budget profile to lay in so we’re not guessing what that budget profile will look like in the future.”

“The intention is still to fly VERITAS,” she said. “We’re really, really looking forward to flying VERITAS in the future.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.