Strategizing planetary defenseby Jeff Foust

|

| “There’s a lot more that we can do than we have resources for, so we need to be strategic,” said Lal. |

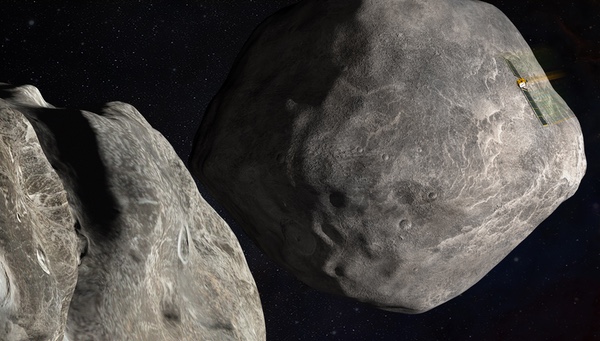

Some NASA officials have used the success of DART to suggest that, if a potentially hazardous asteroid was found coming our way, we have the means to deflect it. “We go with precision and hope that, if a killer asteroid were to threaten the planet, that we could hit it as we did, bullseye, with the DART mission,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said during an event last week to mark the Czech Republic’s signing of the Artemis Accords.

But planetary defense is an ongoing challenge for NASA. “There’s a lot more that needs to be done,” said Bhavya Lal, NASA associate administrator for technology, policy, and strategy, during a panel discussion on planetary defense at last month’s Space Symposium in Colorado Springs. “There’s a lot more that we can do than we have resources for, so we need to be strategic.”

The panel coincided with the release of a planetary defense strategy and action plan document by NASA. Lal said that NASA deputy administrator Pam Melroy requested the strategy last year, which the agency modeled on separate efforts to develop plans for human exploration of the Moon and Mars, such as an architecture also released by NASA during the conference.

That used an approach called “architect from the right and execute from the left,” creating a set of objectives and working backward to turn those objectives into efforts that can be achieved through a set of projects and programs. The planetary defense strategy, she said, also borrowed from NASA’s climate strategy, which identified challenges to be overcome.

The strategy found six such challenges, perhaps the biggest of which is finding and characterizing near Earth objects (NEOs). Ongoing surveys have done a good job with the largest objects: about 95% of the predicted NEOs one kilometer in diameter or larger have been found, based on models of the population of such objects and the rate at which new ones are found.

However, that discovery rate drops off for smaller objects. Lindley Johnson, NASA’s planetary defense officer, noted on the panel that there should be about 25,000 NEOs at least 140 meters across, the size at which an impact would cause regional damage. Congress set a goal in a 2005 NASA authorization act of finding 90% of such objects by 2020. As of the end of 2022, about 42% of that population has been found. “We’ve got a ways to go,” he said.

If NASA relied on existing surveys alone, it would take a very long time to reach that goal. The strategy estimated that, by 2040, current surveys would have discovered only 58.7% of the NEO population at least 140 meters across.

Fortunately, two projects should help. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a large telescope funded by the National Science Foundation and nearing completion in Chile, will be able to significantly increase NEO discoveries once it enters operations in 2025.

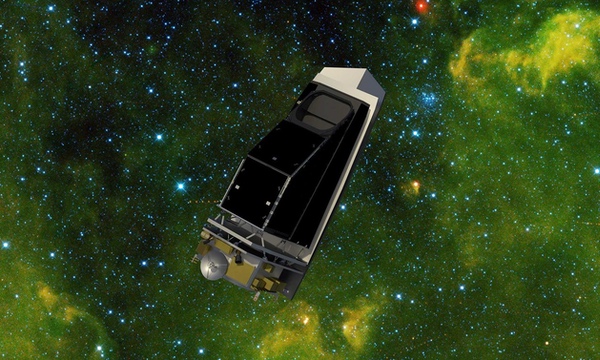

An even bigger boost will come in 2028 with the launch of NASA’s NEO Surveyor mission, an infrared space telescope optimized for search for NEOs. “It’s like clockwork to really clean up on finding the rest of this population,” Johnson said. The NASA strategy estimates that the combination of existing surveys, Rubin, and NEO Surveyor would hit the 90% threshold in 2034 and find nearly 95% of the NEOs at least 140 meters across by 2040.

The NASA strategy suggested other opportunities to discover NEOs through data collected from space domain awareness projects that seek to track and identify satellites and debris in Earth orbit, as well as future such capabilities in cislunar space. In the longer term, the strategy called on the using “maturing commercial capabilities” for tracking and characterizing NEOs.

A second challenge involves mitigation of impacts. That could involve future missions to characterize asteroids like Apophis when it makes a close, but harmless, flyby of Earth in 2029—the subject of a conference later this week—or even demonstrations of deflection technologies like DART. Related work includes assessment of deflection technologies and the specific complications posed by one such technology, nuclear weapons.

| “This is a problem we know how to solve,“ said Mainzer of NEO Surveyor’s mission. “How many global problems do we know how to solve that are of the order of $1 billion?” |

The other four challenges focus less on science and technology then on policy and organization. One challenge addresses growing international interest in planetary defense and NASA’s roles in helping support that through sharing of data and expertise. A second deals with the need for greater interagency cooperation in the federal government, such as with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which would led the response to a NEO impact. Two others look at how planetary defense activities are managed within NASA and how the agency should communicate that work.

Notably, while the strategy outlines a set of goals and activities to achieve them, it is silent on estimated costs, a deliberate choice. “You’re not designing your plan according to your budget, but you have a vision and, when you have a budget, you figure out what pieces fit,” Lal said.

Budgets have been an issue for planetary defense projects, notably NEO Surveyor. NASA pushed back its launch from 2026 to no later than 2028 last year, citing budget pressure from other programs in NASA’s planetary science portfolio. While Congress partially restored the funding for the mission, NASA said that was not enough to prevent the schedule slip.

The strategy noted that having the Planetary Defense Coordination Office located within NASA’s planetary science division “may limit opportunities for expanding planetary defense activities” given competition from large missions there. It proposed that NASA conduct an independent assessment of the best location within NASA for the office, but added that “competition for funding is likely to be an issue regardless of where the program is situated.”

NASA’s fiscal year 2024 budget proposal requested $250 million for planetary defense activities, with all but $41 million of that going to NEO Surveyor. That budget is projected to grow to $400 million in 2026, driven by development of that mission, before declining as the mission approaches launch.

When NASA confirmed NEO Surveyor for development last September, it estimated the mission will cost $1.2 billion, a price tag that surprised many in the planetary science community. The mission was once proposed as a Discovery-class mission with a far lower price tag and, as recently as 2019, was projected to cost $600 million. NASA officials said that that increase is due in part to the decision to stretch out its development, saving money in the near term but increasing the mission’s overall cost.

Amy Mainzer, survey director for NEO Surveyor at the University of Arizona, defended the cost at an advisory committee meeting in January. “This is a problem we know how to solve. How many global problems do we know how to solve that are of the order of $1 billion?”

A illustration showing DART about to collide with Dimorphos last September. The NASA strategy opened the door to future missions to demonstrate planetary defense technologies. (credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL) |

An updated national planetary defense strategy

The NASA planetary defense strategy came out just a couple weeks after the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) released its own document on the subject, the National Preparedness Strategy and Action Plan for Near-Earth Object Hazards and Planetary Defense. That document is an update of a similar plan released in 2018 that takes a whole-of-government approach to roles and responsibilities for planetary defense.

The timing of the two strategies was coordinated. “We had a chance to work together and make sure that the strategies were aligned, and NASA’s action plan flowed from the national strategy,” Lal said.

The updated White House strategy looks similar to the NASA one, with goals to enhance detection and characterization of NEOs, improve modeling them, and work on mitigation technologies. It also endorses improved international and interagency cooperation as well as preparing responses to NEO impacts.

| “If our interests don’t align globally on Earth not being hit by asteroids,” Matthews said, “I don’t know where we are.” |

“We’re kind of at an inflection moment for the field of planetary defense,” said Matthew Daniels, assistant director for space security and special projects at OSTP, during the Space Symposium panel. The updated document, he said, reflected what had happened over the last five years and what’s planned over the next few years.

The White House Strategy identifies two key areas for the next decade. One is to improve NEO detection and characterization, like what NASA outlined in its own strategy but also identifying contributions from other agencies, like NSF, NOAA, and the Defense Department. An example of that is the NSF taking the lead, in cooperation with NASA and the DOD, to identify deep space radar capabilities for studying NEOs that can replace the destroyed Arecibo Observatory.

A second key area is in international cooperation. “The United States has the opportunity to lead in creating new multilateral initiatives and cooperating with new partners worldwide on planetary defense,” the OSTP strategy states, both in bilateral relationships and multilateral fora like the UN’s Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS). The State Department will play a major role in those efforts, supported by NASA and other agencies.

“This is something that we want to talk to the world about and work with in multilateral settings,” Daniels said. He noted that the White House timed the release of the updated strategy to coincide with an international planetary defense conference taking place in early April in Vienna, at the home of COPUOS.

“If our interests don’t align globally on Earth not being hit by asteroids, I don’t know where we are,” he said.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.