From the sky to the mud: TENCAP and adapting national reconnaissance systems to tactical operationsby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The Army Space Program Office (ASPO) was established in 1973. It was small and selective, and it placed Army personnel in the different NRO program offices “to do good things for the Army,” in the words of one of the people involved. |

But by the early 1970s, the customer base for these expensive and top secret systems began to change. The Navy had already started exercises to use satellites to detect and track Soviet naval vessels, and ocean surveillance would become a major mission by the middle of the decade. The United States Army became interested in using intelligence satellites to provide information to tactical forces as part of what came to be known as the Tactical Exploitation of National CAPabilities (TENCAP) program. The early focus of TENCAP involved bringing data collected by low Earth orbiting electronic intelligence (ELINT) satellites, primarily small Program 989 satellites, directly to deployed US Army units in Europe and Korea, bypassing the large ground terminals and satellite dishes in fixed locations in the United States—and also bypassing the National Security Agency, which sought to control the flow of signals intelligence data.

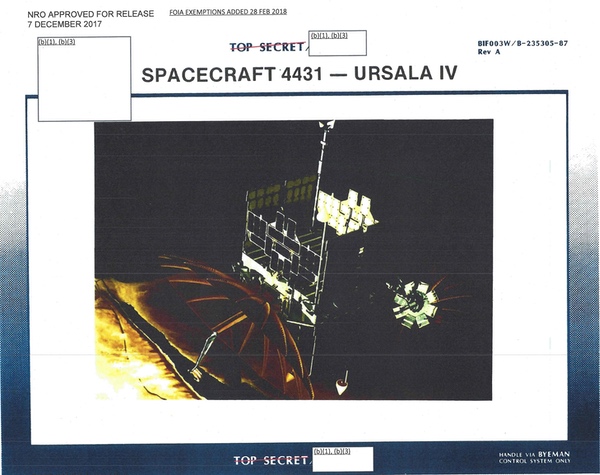

The Program 989 satellites were about the size of a suitcase when folded up, but upon reaching orbit they unfolded solar panels and numerous antennas. They spun rapidly, sweeping their antennas over the ground below and gathering up signals from various emitters such as surface-to-air missile system radars. Starting in the 1970s, these satellites were equipped with a direct downlink capability to send their data to small, mobile ground stations developed by the Army Space Program Office and the National Reconnaissance Office. The URSULA IV satellite was launched in 1979 and provided data to ITEP/TUT systems in West Germany and elsewhere. The satellite was named after movie star Ursula Andress, and was spelled both “Ursula” and “Ursala” in NRO documents. (credit: NRO) |

Program 989

Starting in 1963, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) began launching a series of suitcase-sized satellites as part of Program 989. The P989 satellites were rectangular with antennas sticking out of their sides, and spun rapidly as they flew around the Earth in polar orbits, their antennas sweeping across the face of the globe and gathering signals from below. Most of the satellites collected data on Soviet radar systems, and in the latter half of the 1960s many of them were specifically tasked with gathering signals from Soviet anti-ballistic missile (ABM) radars. Some also had the goal of collecting technical and location data on air search and anti-aircraft radars. They stored their information on tape recorders and then later beamed that down to the ground where it often took signals experts weeks or months to process the data. The information was then used by intelligence analysts to understand Soviet ABM capabilities, or by Strategic Air Command to assist in development of strategic bombing plans, such as helping B-52 bombers avoid Soviet air defenses. The long processing times and the satellites’ targets meant that for the first decade of their existence they had almost no value to tactical forces. That began to change by the 1970s.[1]

The number of P989 satellites launched per year was never high, peaking at four in 1968 and another four in 1969. After that, the launches dropped significantly. There was one launched in 1971, two in 1972, one in 1973, two in 1974, and then one each in 1976, 1978, and 1979. The satellites had code names like MABELI, RAQUEL, and URSULA—the last had increased capabilities that made it of greater use to tactical forces. The FARRAH I satellite was launched in 1982, followed by FARRAH II in 1984. Assuming a single satellite constellation, the launch rate indicates that the satellites had at least a two- to three-year lifetime by the late 1970s, although an official history indicates that FARRAH I was still operational by the mid-1990s after more than a decade in orbit. Additional, significantly larger P989 satellites with greater capabilities were launched by the late 1980s.

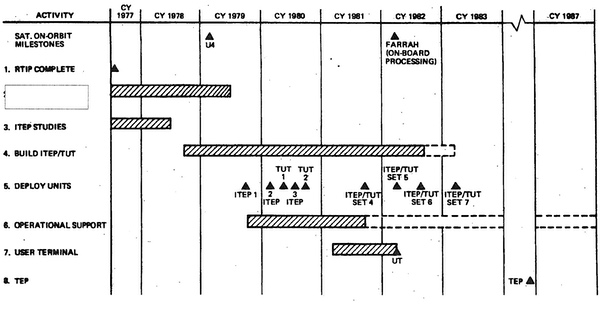

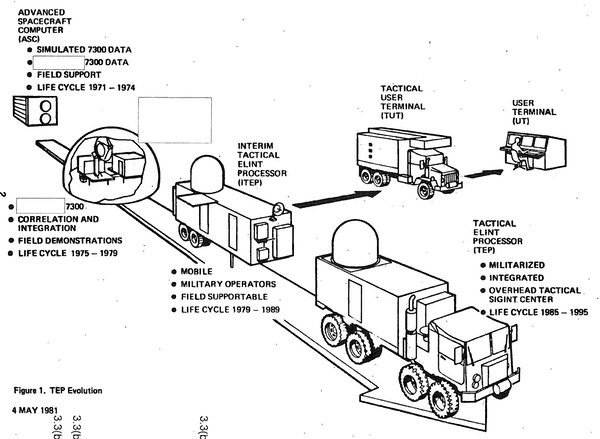

The development history for the ITEP/TUT started with early tests in 1972 with the first deployments occurring in 1979 and 1980. (credit: NRO) |

Bringing P989 to the ground

The Program 989 satellites and their electronic intelligence payloads were developed by the NRO’s Los Angeles field office, known as the Secretary of the Air Force Special Projects Office and usually referred to as either SAFSP or “special projects.” SAFSP oversaw P989, and the satellites were manufactured by Lockheed Space and Missile Company in Sunnyvale, California, with the ELINT payloads developed by various companies and then integrated onto the small satellites.

The P989 satellites were equipped with tape recorders to record their data while over the Soviet Union and then play it back over a ground station in the United States. The ground stations were fixed, and their antennas and associated equipment were large. But by the 1970s, the NRO began making the satellites capable of directly relaying their collected data to the ground if a ground station was in sight while the satellite was over denied territory. This meant that in areas of the world where the United States had a presence close to the borders of adversary countries, the satellites could provide their collected signals intelligence data directly to ground stations without recording it first, known as direct downlink (DDL). Obvious locations included Europe, Korea, and Japan, where the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact nations were not far away.

SAFSP, along with the Army, began a series of classified experiments named “Cauldron” at Fort Hood (now named Fort Cavazos), Texas, in the early 1970s. The goal was to determine what national-level intelligence systems could do for tactical Army users.[2] The Program 989 satellites, which were being upgraded to include the ability to directly readout their data to small ground stations, were the focus of these experiments.

The Army Space Program Office (ASPO) was established in 1973. It was small and selective, and it placed Army personnel in the different NRO program offices “to do good things for the Army,” in the words of one of the people involved in the early efforts to develop Tactical Exploitation of National CAPabilities systems. The ASPO reported to the General Officer Steering Group for direction and requirements. The philosophy those engaged in these efforts adopted for TENCAP was to seek a 90% solution rather than trying to fulfill all the requirements. That approach involved using best commercial practices and accepting that adopting military specifications (known as “mil-spec”) was not always the best solution. Finally, those involved sought to achieve Pre-Planned Program Improvement (P3I), in other words, planning for eventual upgrades, but not waiting until they were available before introducing an interim system to field units.[3]

In the mid-1970s, the US Army along with the NRO began work on what was eventually named the Tactical ELINT Processor/Tactical Unit Terminal system, also known as TEP/TUT. Whereas the Air Force and the Navy had long been direct participants in the National Reconnaissance Office, the U.S. Army had very little direct participation in the NRO, but during a short period of time the Army became an enthusiastic consumer of NRO-produced intelligence. Subsequent military field exercises and concept demonstrations proved that providing ELINT data from satellites was potentially valuable.[4]

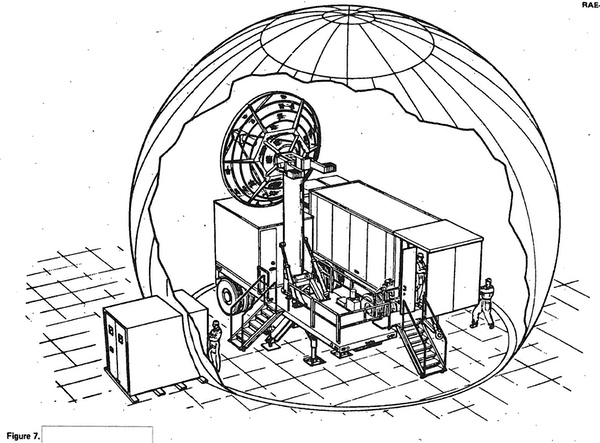

Test hardware developed in the mid-1970s involved an inflatable dome that encompassed both a large dish antenna and other equipment. Later iterations used smaller dishes and achieved greater mobility. (credit: NRO) |

From 1971 to 1974, the NRO worked on the Advanced Spacecraft Computer (ASC). The ASC was a hardware/software combination developed for use on board future 989 satellites. The ASC term applied both to the equipment on the satellite as well as on the ground, and the ASC was to provide certain types of data to field commanders in a more useful form. From 1975 until 1979, they developed a demonstration system that consisted of a dish antenna and a processing van, both mounted on separate small trailers. These were protected from rain and the elements by a large dome. The dome also enhanced operational security, because no hostile element would be able to observe the dish tracking a low Earth orbit satellite. They required setup time and were not suitable or intended for deployment.[5]

In 1975, a still-classified contractor referred to by the NRO by the designation “BIF-77W” developed a computer, peripherals, and two color monitors so that an analyst could interact with the ELINT data coming down from the satellite. The equipment was packaged in a transportable TEMPEST secure van. The name of the processing facility is still classified. In 1976, the terminal supported the Bold Eagle exercise at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada.[6]

| The purpose of the TEP/TUT was to gather ELINT data, such as the emissions and locations of Soviet radars, from far behind enemy lines and transmit that data to US ground forces and do so quickly, so that US forces could use that information for war planning. |

In 1976, a transportable terminal and upgraded software were added to support another exercise, probably involving naval forces. It was used to support Navy Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercises, as well as capability demonstrations at the contractor facility. A transportable antenna 4 meters (14 feet) in diameter proved that satellite signals could be collected down to very low elevation angles. In 1977, the system was substantially improved with the addition of data correlation software. Although the details remain classified, that system was apparently also capable of receiving data from the NRO’s POPPY signals intelligence satellites, which were about to be retired and replaced by a new system. POPPY had been developed by the Naval Research Laboratory for the NRO, and by that time had been adapted to a naval surveillance role.[7]

Because Special Projects developed the P989 satellites, the office also took on the development of the tactical terminals.[8] Robert Mihara at SAFSP was put in charge of the project, which was handled in two of SAFSP’s offices designated SP-6 and SP-8. SP-8 was then in charge of developing signals intelligence satellites and its program director, Colonel Paul Foley, did not want to stay in the business of developing ground terminals. After the initial development, responsibility for these systems was transferred to another SAFSP office known as SP-10.

By the late 1970s, the demonstration system had evolved into TEP/TUT. The project incorporated the separate elements such as the satellite dish and processing equipment into a single larger trailer. The satellite dish antenna was mounted inside the trailer and, along with a protective dome, it would elevate to stick out above the trailer. The data would then be sent to the TUT inside a small van, where operators would look at the intelligence data. The purpose of the TEP/TUT was to gather ELINT data, such as the emissions and locations of Soviet radars, from far behind enemy lines and transmit that data to US ground forces and do so quickly, so that US forces could use that information for war planning. One of the uses of the system was to plan safe aircraft access routes to avoid enemy air defenses.[9]

The Soviet SA-6 surface-to-air missile system was a mobile missile system in use during the 1970s and later. It was one of the targets of the ITEP/TUT system. Locating the radar systems in Warsaw Pact nations could give the US Army an indication of where Soviet armored forces were deployed. This was important for targeting as well as avoiding the missiles. |

One target of particular interest to the Army was the Soviet SA-6 road-mobile surface-to-air missile (SAM) system. An SA-6 battery— designated the 2K12 “Kub” system by the Soviet Union—consisted of several tracked vehicles each carrying three low-medium-altitude missiles, and another tracked vehicle carrying a “Straight Flush” radar. The radar had an effective range of 75 kilometers and could be detected from space. Because SA-6s were used to protect ground forces, their presence could indicate the location of major Soviet military activities, thus giving away the position of other armored vehicles. In addition, the SA-6s would pose a threat to Army helicopters and tank-busting A-10 Warthogs, so knowing their locations would be important for allied aircraft hunting Soviet tanks during a conflict in Western Europe.

Mobility was a key goal for the Army’s TENCAP systems. This meant that the equipment had to be mobile, mounted on trucks or trailers that could be carried in Air Force transports. All TENCAP equipment could be moved by C-130 aircraft, but C-5s were the preferred mode of transportation as the equipment could be loaded and unloaded much faster.

The A-10 Warthog was a primary means of defending West Germany from Soviet invasion during the 1970s and 1980s. The ITEP/TUT systems would help Army aviators and Warthog pilots avoid Soviet mobile surface-to-air missile systems. (credit: USAF) |

Developing ITEP/TUT

The terminal was used in demonstrations at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, in 1978 and to support Strategic Air Command exercises in Nebraska in 1979.[10] The Army introduced the test system into exercises. Two exercises took place in 1978, Gravity Score (continental United States) and Coldfire (Europe), using national systems for tactical commanders.[11]

The Interim Tactical Electronic Processor was first deployed at Giessen Army Airfield in Germany during operation REFORGER 1979. (REFORGER stood for “REturn of FORces to GERmany.”) ITEP was later renamed the Electronic Processing System (EPDS).[12] But gaining wider acceptance of this new system would require a sales effort by SAFSP, which did not have to convince many in the Army as much as it needed to convince the people in Washington who controlled the budgets, as well as skeptical NRO leadership.

REFORGER (REturn of FORces to GERmany) was a major annual exercise to send American troops to Germany for exercises and to demonstrate to the Soviet Union that the United States was supporting its NATO allies. An early test of the use of satellite collected intelligence occurred during a REFORGER exercise. (credit: US Army) |

The head of SAFSP in the late 1970s, Brigadier General Jack Kulpa, knew that the new capabilities provided by the TENCAP vans was not well understood in the military, and so SAFSP arranged to conduct a demonstration in the Washington DC area. The development van was transported from California to Andrews Air Force Base in the dead of night on an Air Force transport plane. Kulpa remembered getting a call at three in the morning from Robert Mihara saying that there had been a problem unloading the van from the plane. “We dropped it,” he told the general. Fortunately, there was no serious damage from the incident.[13]

The van was transported to NSA Headquarters at Fort Meade, Maryland, in the Washington suburbs. The Army Corps of Engineers had supported the set-up, and the van was put in a field surrounded by two rows of barbed-wire fencing and a wooden plank walkway out to the van. Kulpa remembered that Hans Mark, Director of the NRO, was skeptical of the TEP project. Kulpa and Mark drove out to the site and it had rained heavily, turning the field into “a quagmire of mud.” The muddy field in the middle of the night was a stark contrast to the air-conditioned satellite control and processing stations of Washington and Sunnyvale, showing how satellites developed to serve the CIA and Strategic Air Command could be used to support troops deployed to the field. “It looked and felt like a real combat situation,” Kulpa explained of the messy walk out to the van. The system worked perfectly, demonstrating an Eastern European combat scenario. “Our guys were all in combat dress and it really was impressive,” he added. Hans Mark was impressed and became a supporter of the program.

The first TENCAP system, the Interim Tactical Electronic Processor (ITEP), deployed to Germany in 1979. It was later renamed the Electronic Processing Data System (EPDS). It provided near-real-time national electronic intelligence data to tactical commanders. The satellite dish was concealed under a dome and could be raised once the system was in place. (credit: US Army) |

Soon SAFSP also built an ITEP system for the Air Force, and in 1979 sent a development van and simulation capability for an Air Force Blue Flag exercise at Hurlburt Field, Florida. Blue Flag, which still continues annually, is an attempt to duplicate theater conditions and procedures as closely as possible. Before each exercise, planners research friendly and enemy force structures, communications capabilities, logistics support, command and control procedures, and current plans and directives. Now the ELINT satellite data was being integrated into the exercise along with various other forms of simulated intelligence collection.[14]

| The muddy field in the middle of the night was a stark contrast to the air-conditioned satellite control and processing stations of Washington and Sunnyvale, showing how satellites developed to serve the CIA and Strategic Air Command could be used to support troops deployed to the field. |

The 1979 exercise simulated a Soviet invasion across the Fulda Gap in Germany—a nightmare scenario for NATO forces. Fulda was a lowland area between East and West Germany, and the expected site of a Soviet tank invasion of the West. During the Blue Flag exercise, Rich Wendt of SAFSP briefed the Deputy Commander of the 9th Air Force about the new system. “When he saw a screen shot from the ITEP he complained that there was no intelligence value in seeing a solid wall of black dots representing Soviet air defense radars in East Germany,” Wendt recalled. Although the general was dismissive, one of his captains was not, noting that the large number of radars was a clear sign of how difficult the task of dealing with East Germany’s air defense would be in event of war.[15]

US Army aviation was a primary beneficiary of the ITEP/TUT system developed in the 1970s and deployed in the 1980s. Army attack helicopters could be directed to attack Soviet invasion forces based upon data collected by the Program 989 satellites. (credit: US Army) |

Washington oversight

The NRO and the Army had started with the small P989 ELINT satellites because the data was already coming down in a form that could be quickly collected, processed, interpreted, and disseminated. At the time, the NRO’s imaging satellites used film, and distributing the images to tactical level users could take days after the film was returned to Earth, and often significantly longer after the photos were first taken in orbit. By late 1976, the NRO fielded the first digital imaging system, the KH-11 KENNEN, and it became conceivable that the imagery it collected could also be sent to tactical users. When TENCAP systems for satellite imagery were developed, however, they required far more equipment than the ITEP/TUT.

TENCAP started to grow during the 1970s and, particularly with the debut of digital imaging systems, officials in the executive and legislative branches realized that there would be new opportunities and sought to manage the growth. The Department of Defense created the Defense Reconnaissance Support Program (DRSP) to coordinate DoD use of this new data. In 1977, Congress mandated that each military service have a TENCAP representative. The TENCAP entity was required to independently perform an impact statement for Congress indicating how its warfighting missions would be affected by any proposed space reconnaissance system.[16] That congressional requirement served to force the services to better explain how they would use national systems, and Congress was apparently skeptical of some of their plans and spending, as well as how the Army was already introducing the ELINT data to its field units.

The Army approach was to build prototype systems using best commercial practices, field them, and learn from operational experience on how to best use the national systems. As one Army TENCAP summary explained it, the Army’s TENCAP philosophy was “get it out to the user, test it with the user, listen to the user, and make changes based on the user.”[17] But congressional staffers believed that the operational concept should be well defined prior to the fielding of prototype systems. According to one assessment, “the Army is interested in driving future system development toward tasking independence, better geolocation accuracy, more timeliness, and more response access in the area of interest.”[18]

Tactical commanders were also concerned that the intelligence was not releasable to their allied counterparts, although during wartime the restrictions might have been lifted. This was a bureaucratic headache that the organizations would have to work through. As one assessment noted, a 1973 policy already allowed for national level ELINT data to be “decompartmented”—meaning removing some security restrictions—but some agencies had added their own restrictions, complicating the release of the data.[19] In 1976, Director of Central Intelligence George H.W. Bush urged President Gerald Ford to declassify the “fact of” satellite reconnaissance. He also sought the reduction of restrictions on the dissemination to tactical forces of intelligence derived from NRO satellites.[20]

Another concern was that users might be overwhelmed by data, but experience had shown that simple automatic processing could solve most of those problems. For instance, during one exercise, the Air Force had assigned an officer to review 2,000 electronic intercepts per day. Although that appeared to be too much for a single person, the officer consulted with his commanders and processed only the intercepts concerning a couple of electronic emitters, ignoring 90% of the received volume. “It was evaluated that the ten percent of the information processed in this manner significantly added to the command’s combat capability and that the unprocessed ninety percent did not seriously detract from the command’s ability to operate,” according to one summary.[21]

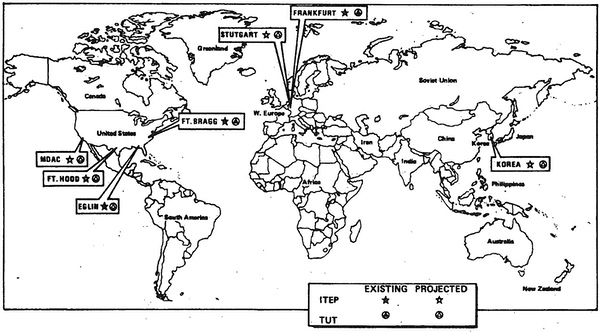

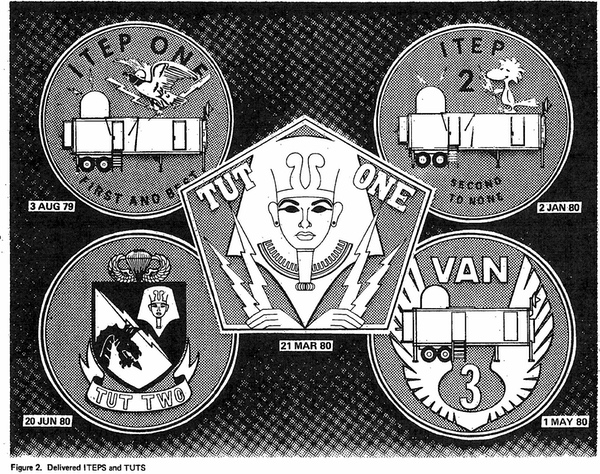

The Interim Tactical ELINT Processor and Tactical User Terminals were deployed to Army units around the world starting in 1979. (credit: NRO) |

Deploying ITEP/TUT

The Army built Interim TEPs (designated ITEPs) and two TUTs and deployed operationally to the Army V Corps in Frankfurt, West Germany, and the 18th Airborne Corps at Fort Bragg (now renamed Fort Liberty), North Carolina. An ITEP (with no TUT) was soon operating with the Air Force at Hurlburt Field, Florida. ITEP 1 was accepted into service in August 1979, followed by ITEP 2 in January 1980. TUT One was accepted in March 1980 and followed by Van 3 and TUT Two in June 1980.[22]

| Although the Army embraced ITEP/TUT and funded and deployed it, a Defense Intelligence Agency official indicated that the existence of the system was not popular with many in the military. |

In July 1981, three more ITEP/TUT systems were built for deployment to the Army VII Corps in Stuttgart, West Germany, III Corps at Fort Hood, Texas, and 8th Army in Korea. There was a contract option for a fourth ITEP/TUT system to be made available for training and development studies at the contractor’s facility. A User Terminal, which would be similar to the TUT but have two remote operator positions, was also developed and built for deployment with the Air Force ITEP.[23]

With the deployment of the operational systems, ITEP/TUT was soon used in multiple field exercises. Between 1979 and 1980, V Corps used it in exercises Constant Enforcer, Post Oak II, Certain Rampart, and Shockwave II. In 1980, the 18th Airborne Corps used the system in Solid Shield, Positive Leap, and Bragg Exercise. The Air Force used its ITEP system during 1981–1982 in various Blue Flag exercises as well as exercise Border Star.

A militarized TEP was also under development at that time.[24] This meant that it was built with mil-spec components rather than the commercial components used in the earlier systems. Based on the level TENCAP systems were fielded to (primarily Corps and Echelons Above Corps units) best commercial practices proved to be adequate and these systems worked well with an operationally ready rate in the high 90%. Part of this was the assignment of civilian contractor field service representatives (FSRs) to almost everywhere an Army TENCAP system was fielded. Normally there were two FSRs, one who was focused on software and one on hardware. FSRs deployed with TENCAP systems in the first Gulf War. Each TUT had six to eight analysts who would correlate the data provided from the satellites with other intelligence information to produce a better understanding of the location of enemy forces.

The Enhanced Tactical User Terminal (ETUT) added capabilities and replaced the much smaller TUT in the 1980s. (credit: US Army) |

The TUT turned out to be a less-than optimum solution for the Army’s requirements and there was soon discussion about replacing it. Discussions between the Army Space Program Office and the National Reconnaissance Office led to the development of the Enhanced Tactical User Terminal (ETUT), which was fielded to units that were receiving ITEP/EPDS systems. The Tactical User Terminal was mounted on a truck and was relatively small. The Enhanced TUT was about twice as large and mounted on a trailer. The TUT and later ETUT took the ELINT data from the EPDS and could also combine secondary disseminated national imagery—meaning that it was not taking imagery directly from a satellite, but using imagery that was otherwise disseminated to military forces.[25] By the late 1980s the only TUT left was at Maastricht, Netherlands in support of III Corps (Forward).

The TUT system was designed to handle information at what was known as the collateral secret level, making it available to a wider number of Army users. But at collateral secret, it couldn’t handle a number of functions that were needed. Collection management (submitting requests for coverage of targets) was at the secret compartmented information level for NRO satellites. The Army developed a capability to remotely locate the Collection Management Support Terminal (CMST) via fiber-optic cable. As an example, an ETUT was located in a secure compound on Campbell Barracks, Headquarters US Army Europe (USAREUR) in Heidelberg, Germany, but the DCSINT Collection Management Office (CMO) was on the third floor of Building 12, the headquarters building, where it was even more secure. The Army buried a permanent fiber-optic cable between the compound and the CMO.

All national imagery—like the images produced by the KENNEN satellites—was either secret or top secret (with other restrictions), so secondary dissemination from the USAREUR Imagery Exploitation System (UIES) to the ETUT had to be at the top secret compartmentalized information level. There was a similar architecture in XVIII Airborne Corps. Plans were in place to do similar architectures with I, III, V, and VII Corps in Europe, but the end of the Cold War curtailed them. The Army also added analytical processing power to the ETUT for the ELINT product.

The Electric Processing and Dissemination System which replaced the ITEP was a large trailer that could be towed behind a military truck and was the primary data processor. Along with the ITEP, it had the direct downlink and the processing capability that turned the data into a finished single-discipline intelligence product. The TUT, and later the ETUT, was a secondary, all-source system capable of receiving data from an EPDS as well as other national data, such as imagery. It could receive that other data via the Tactical Related Applications (TRAP) broadcast system, which provided worldwide dissemination of high-interest ELINT as well as contact reports and parametric information at the secret level. The ETUT could also receive secondary imagery dissemination from Army TENCAP systems capable of receiving national imagery intelligence data. The ETUT could create an all-source picture of the battlefield useful to the generals and their staffs.

Almost all of the TENCAP systems had the Synthesized UHF Computer-Controlled Equipment Subsystem (SUCCESS) radio in them. This was acquired and fielded under an unclassified contract, which was a rarity in the NRO at the time. SUCCESS could receive and transmit via multiple UHF frequencies simultaneously. For example, it could receive the TRAP broadcast while sending out other data via UHF satellite communications.

The first use of national imagery directly downloaded to tactical forces came during the REFORGER 1980 exercise with the Digital Imagery Test Bed (DITB) at Echterdingen Army Airfield. But the DITB was a much larger system than the TUT, with multiple trailers and vehicles.[26]

By April 1982, both EPDS and ETUTs were fielded to V Corps in Frankfurt and VII Corps in Stuttgart, West Germany. They were also sent to XVIII Airborne Corps at Fort Bragg, and I Corps at Fort Hood. The EPDS was also fielded to Korea (8th Army) and the 513th Military Intelligence Brigade (United States Army Central Command) in Fort Gordon, Georgia (now renamed Fort Eisenhower), although the latter did not receive it until the 1990s.

In the late 1970s, Congress directed that the DoD better coordinate its TENCAP programs, and as the Army began to field its systems, and new satellite and other national-level systems were being planned, this issue took on increased urgency. Coordination was also required so that potential users could be made aware of opportunities and capabilities, and could also relay their requirements to the intelligence community. In June 1981, the first meeting of an ELINT Exploitation Working Group was held. At that time, it was clear that some major new capabilities would become available by the end of the decade, resulting in substantially expanded ELINT collection, and coordination and consultation was vital.[27]

The CIA and DoD also established a Tactical Support Group to provide “the resource management coordination under which the Director of Central Intelligence, in concert with the DoD, will develop an integrated basis of NFIP systems’ support for the needs of the tactical forces.” The Tactical Support Group was to coordinate the evaluation of the individual services’ TENCAP assessments.[28]

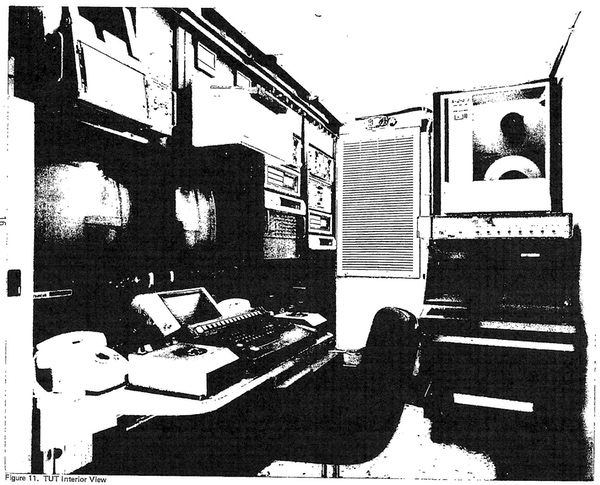

The inside of the tiny Tactical User Terminal deployed in the early 1980s. (credit: NRO) |

Although the Army embraced ITEP/TUT and funded and deployed it, a Defense Intelligence Agency official indicated that the existence of the system was not popular with many in the military. The combined commands, which had responsibility for protecting geographic areas such as the continental United States, did not like that the intelligence data was bypassing them and going to lower-echelon units. According to a summary written in 1986, “NSA also doesn’t like TENCAP because it loosens its grip on the systems it flies.”[29] But the summary noted that “the NRO’s involvement is heavy and positive,” adding that “the new Space Command is maneuvering to become the ‘super TENCAP’ for the” combined commands.[30] By 1986, the Army was spending $86 million on TENCAP, with the Air Force spending $5 million and the Navy $7 million.[31]

The Army became a major user of the data throughout the 1980s. This was new for the National Reconnaissance Office, because the Army had not been one of its key customers for the first few decades of the NRO’s existence. But within a decade, the primary rationale for the effort was upended. “Who would have guessed that ten years later there would be no East Germany, nor any Soviet air defense armada in Europe?” SAFSP official Rich Wendt asked. Fortunately, the Army’s insistence that the system be mobile meant that it was still valuable after the end of the Cold War.

By the late 1980s there was an effort to downsize the ETUT by testing the Tactical High-Mobility Terminal.[32] But before that happened, TENCAP went to war.

The evolution of the early Tactical ELINT Processor systems during the 1970s and into the 1980s. The US Army was a major innovator in the use of national-level intelligence collection systems to support troops in the field. (credit: NRO) |

Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm

In 1990, both 18th Airborne Corps and VII Corps’ EPDS and ETUTs deployed with their respective units to Saudi Arabia for Desert Shield/Desert Storm. The Army also deployed Forward Area Support Terminals (FASTs) to XVIII and VII Corps. FAST was a version of the ETUT that could provide data at a lower level of secrecy. By this time there were other national-level sources of intelligence that were of interest to the military. In addition to the EPDS, ETUT, and FAST systems deployed to Saudi Arabia, the Army had the Tactical Radar Correlator (TRAC) that took a direct downlink from the ASARS radar system carried in the U-2 reconnaissance aircraft. That system was shipped to Saudi Arabia before the end of August 1990 and it was crucial for targeting Iraqi armor for A-10s and other coalition aircraft. The Army also shipped the USAREUR Imagery Exploitation System (UIES) to Saudi Arabia. It was designed to receive national imagery data sent in response to Army requirements.

A key component of the UIES was its Receive Location (RL). Per Army doctrine, these were mobile, so it could deploy forward as needed. CENTCOM Headquarters also had an RL, but it was installed in a building in Tampa and could not be deployed forward. Army doctrine of making all of the TENCAP systems “mobile” (as mobile as a 12-meter [40-foot] long van could be) was validated by Desert Shield/Desert Storm. The Army shipped the TRAC, UIES, and VII Corps’ EPDS and ETUT from Rhein Main Air Base in Germany to Saudi Arabia, and set them up before hostilities started.

The ITEP/TUT system was first deployed starting in 1979. Details of the program have only been declassified in the past year. (credit: NRO) |

The Army fights for direct downlink

The Army invested a significant amount of money in the programs and by the mid-1990s had equipment fielded to every major Army unit from Division to Echelons Above Corps (EAC). Even in the 1970s, some intelligence officials recognized that increasing use of national-level intelligence would put demands upon those resources and pose other risks. For many years the NRO served the needs of users like the Central Intelligence Agency and Strategic Air Command. They now found that serving more customers meant that those customers could demand more, and create problems if they did not get what they wanted.[33]

| At one point, someone tried to tell Lieutenant General Forster that this was a complicated subject. That was the wrong thing to say, because Forster had a Ph.D. in nuclear chemistry. |

The Army’s commitment to use of national intelligence data was substantial, which gave the service clout over NRO development of new systems. By the late 1980s, the NRO was looking at a new generation of satellites to replace the Program 989 satellites as well as Navy ocean surveillance satellites, combining their missions. The NRO decided not to continue the narrow band direct downlink carried by the 989 satellites. Army leadership sent a letter to the NRO saying in essence that if direct downlink was not included in the new system, the Army would not support it in Congress. As one person familiar with the situation said, “that caused the fecal matter to hit the fan in 4C1000”—4C1000 was the NRO headquarters office in the Pentagon.

A meeting was called there with Deputy Director of the NRO Jimmie Hill, USAF Brigadier General Don Walker, and the Navy admiral who was leading the new program. The Army was represented by Lieutenant General Bud Forster and one staff officer. The meeting was tense. At one point, someone tried to tell Lieutenant General Forster that this was a complicated subject. That was the wrong thing to say, because Forster had a Ph.D. in nuclear chemistry. His reply was essentially, “if it’s too hard for your folks, I’ll explain how to do it…”

The NRO decided to keep the direct downlink capability in the new satellite constellation. This proved to be unexpectedly helpful when the wideband relay on the new satellites failed for a period of time and the only thing keeping the constellation from being useless was the Army DDL that the NRO had originally sought to eliminate.

Throughout the 1990s to the present day, the Army has built new systems and sought to consolidate some of its systems to better combine different types of intelligence—including commercial imagery—and create a more complete picture of the tactical battlefield. Now that documents on NRO satellite programs of the 1970s are being declassified, it is possible to gain a better understanding of what TENCAP was and how it started, and how the US Army led the way.

Endnotes

- Major General David D. Bradburn, U.S. Air Force, Colonel John O. Copley, U.S. Air Force, Raymond B. Potts, National Security Agency, [deleted name], National Security Agency, “The SIGINT Satellite Story,” National Reconnaissance Office, 1994, p. 125.

- “Army TENCAP (A very informal history as remembered by me…)” Army Space Program Office.

- Ibid.

- “ITEP/TUT Program Historical Report,” July 31, 1981, p. 1.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 8.

- Peter Swan and Cathy Swan, with editor Rick Larned, published the book Birth of Air Force Satellite Reconnaissance: Facts, Recollections and Reflections, SAFSP Alumni Association, 2015, pp. 75-77.

- “ITEP/TUT Program Historical Report,” July 31, 1981, p. 11.

- Ibid.

- “National/Tactical Interface Issues (remarks are keyed to the questions).”

- “Army TENCAP (A very informal history as remembered by me…).”

- Birth of Air Force Satellite Reconnaissance: Facts, Recollections and Reflections, p. 76.

- 505th Command and Control Wing, “Blue Flag,” April 10, 2013.

- Birth of Air Force Satellite Reconnaissance: Facts, Recollections and Reflections, pp. 75-77.

- [Deleted], Memorandum for the Record, “Intelligence as a Force Multiplier - - Meeting with [deleted] TENCAP Coordination Officer, DIA, 24 April, 1986,” April 25, 1986.

- “Army TENCAP (A very informal history as remembered by me…)” Army Space Program Office.

- “National/Tactical Interface Issues (remarks are keyed to the questions).”

- Ibid.

- Aaron Bateman, “Trust but verify: Satellite reconnaissance, secrecy and arms control during the Cold War,” Journal of Strategic Studies, January 2023, p. 19.

- “National/Tactical Interface Issues (remarks are keyed to the questions).”

- “ITEP/TUT Program Historical Report,” July 31, 1981, p. 1.

- Ibid., p. 18.

- Ibid., pp. 18-19.

- “Army TENCAP (A very informal history as remembered by me…).”

- Ibid.

- Memorandum for Distribution, from [deleted] Program Assessment Office, Intelligence Community Staff, “First Meeting of ELINT Exploitation Working Group,” June 25, 1981.

- Memorandum for: [deleted], Director, Intelligence Community Staff, from [deleted], Director, Office of Program and Budget Coordination, “Personnel Augmentation,” August 24, 1982, with attached: “Tactical Support Group,”

- NSA guarding its turf when it came to signals intelligence satellites was nothing new. According to one source, in the early 1970s the NSA had fought against providing processed ELINT data produced by another satellite named STRAWMAN directly from the Satellite Control Facility in Sunnyvale, California, to US forces in Vietnam. Instead, the data had to be sent through NSA Headquarters in Fort Meade first, adding about an hour to the delivery time for the intelligence.

- [Deleted], Memorandum for the Record, “Intelligence as a Force Multiplier - - Meeting with [deleted] TENCAP Coordination Officer, DIA, 24 April, 1986,” April 25, 1986.

- Ibid. See also.

- “Army TENCAP (A very informal history as remembered by me…).”

- See: Bateman, pp. 18-20.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.