A crisis and an opportunity for European space accessby Jeff Foust

|

| “Ariane 5 is now over, and Ariane 5 has perfectly finished its work and really is now a legendary launcher,” said Israël. “But Ariane 6 is coming.” |

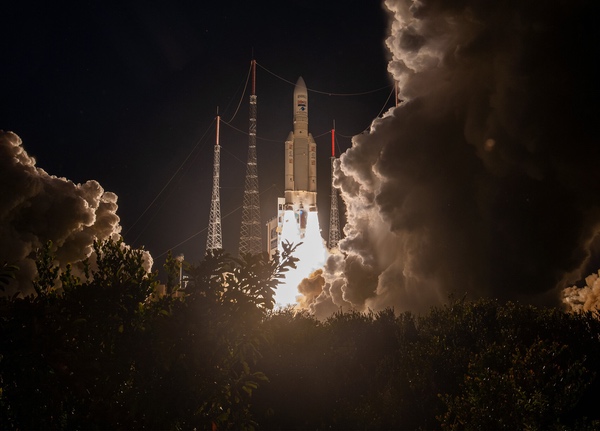

It was the 117th Ariane 5 launch over 27 years. It was also the last Ariane 5 launch, a retirement set in motion years ago. After a shaky start—its inaugural launch in June 1996 “did not result in validation of Europe’s new launcher,” in the infamous phrase of a European Space Agency press release about its explosive failure—it became one of the most reliable launch vehicles available. In its last 20 years of operations, the only black mark on its record was a 2018 launch where an incorrect value in an inertial reference system caused it to place its payloads into an incorrect, but recoverable, orbit.

For much of its career, Ariane 5 was a major player—arguably the major vehicle—in the commercial launch market in an era dominated by GEO communications satellites. It launched several key science missions for the European Space Agency as well as cargo spacecraft for the International Space Station. Perhaps its highest profile mission was the Christmas morning 2021 launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, placing the $10 billion spacecraft on a trajectory so accurate it effectively doubled the spacecraft’s lifetime by allowing propellant set aside for trajectory correction maneuvers to instead be used for later stationkeeping at the Earth-Sun L-2 point.

“Ariane 5 is now over, and Ariane 5 has perfectly finished its work and really is now a legendary launcher,” said Arianespace CEO Stéphane Israël after the deployment of the two satellites on last week’s launch. “But Ariane 6 is coming.”

But the problem for Arianespace, ESA, and Europe’s space industry in general is that Ariane 6 is not yet here. Original plans called for the end of the Ariane 5 to overlap with the start of the Ariane 6, in much the same way as the Ariane 5 overlapped with Ariane 4, which made its final launch in 2003. That would allow for a smooth transition from one vehicle to the next.

However, Ariane 6, once slated to make its debut in 2020, is years behind schedule. That is not necessarily a surprise, given that other new launch vehicles are also well behind schedule. ULA’s Vulcan Centaur’s first launch, also once targeted for 2020, is now delayed until later this year when the company concluded it needed to reinforce part of the Centaur upper stage after a test mishap this spring. Blue Origin’s New Glenn is not expected to fly until at least next year after extended delays. Japan’s H3 rocket, also delayed by years, launched in March, only to fail shortly after stage separation.

ESA announced last October it expected Ariane 6 to make its first launch in the fourth quarter of this year. Both ESA and Arianespace, though, have declined to provide updates, saying they will wait until after more ground tests are completed this summer.

“We have to go through a number of technical milestones over the summer period but I promise, after the summer in September, we will indicate a period which is the target period for the Ariane 6,” said ESA director general Josef Aschbacher during a briefing June 29 after a meeting of the ESA Council in Stockholm.

It is increasingly unlikely, though, that Ariane 6 will be able to make its debut this year. In May, executives with OHB, which produces components for the Ariane 6, said in an earnings call that they expected the first Ariane 6 launch to take place in early 2024, the first formal indication that the launch would slip beyond this year.

“I am getting more and more confident we will see the first launch of Ariane 6 early next year,” said OHB CEO Marco Fuchs. “I think we are within a year of the first launch and that is psychologically very important.”

While ESA has declined to set a new launch date for the Ariane 6, it has provided updates on its development. The most recent one, published June 8, set out a schedule for upcoming tests and reviews for the vehicle. In November, it stated, assembly of the first flight version of the Ariane 6 would begin in Kourou, including a wet dress rehearsal. That schedule would give little time for an Ariane 6 launch before the end of the year even if everything went perfectly—and, so far, things have not gone perfectly.

The first Vega C launch in July 2022. The rocket remains grounded after a failure on its second launch last December. (credit: ESA/M. Pedoussaut) |

Launcher crisis

The delays in Ariane 6 would be an embarrassment, but little else, if that was the only problem for Europe’s launch industry. Instead, it is one of several problems that has temporarily grounded the continent.

Until last year, Europe had relied on three vehicles to launch nearly any spacecraft. For large satellites, there was the Ariane 5 and, soon, Ariane 6. Smaller satellites were served by the Vega and an impending upgrade, Vega C. In between the two was the Russian Soyuz, launching commercial and European government spacecraft from French Guiana.

| ““If, for a couple of months, there’s not a rocket available, it’s bad enough. I’m the first one to call this a crisis,” said Aschbacher. “But this is not something permanent.” |

However, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and sanctions by Europe in response, Russia halted Soyuz launch operations in French Guiana, stranding payloads such as ESA science missions and Galileo navigation satellites. In December, the second Vega C suffered a failure in the Zefiro 40 motor that powers its second stage, destroying two commercial high-resolution imaging satellites.

An investigation traced the failure to a flawed carbon-carbon insert in the nozzle of the motor. Avio, the Italian prime contractor for Vega C, said it would replace that component with one from a new supplier and conduct tests that would allow the vehicle to return to flight before the end of the year. (The original Vega vehicle, which does not use the Zefiro 40 motor, will resume launches in September, but most of the missions on the Vega manifest are for the more powerful Vega C.)

Those return-to-flight activities included a static-fire test of the Zefiro 40 motor. However, Avio announced June 29 that the test, which took place the day before, suffered an anomaly of some kind where the motor’s chamber pressure dropped 40 seconds into the 97-second test.

Avio said it did not know what caused the pressure drop but said that the new carbon-carbon component did not appear to be at fault. “This aspect will require further investigation and testing activity to be conducted by Avio and the European Space Agency to ensure optimal performance conditions,” the company said in a statement about the test.

That setback makes it unlikely the Vega C will return to flight this year. “We have to see in detail what this anomaly will mean” for those plans, ESA’s Aschbacher said at the ESA Council briefing. “This will have an impact because it was a very important milestone on our roadmap to the return to flight for Vega C.”

The problems with Vega C, continued delays with Ariane 6, and the loss of the Soyuz for geopolitical reasons mean that, with last week’s Ariane 5 retirement, Europe temporarily lacks the means to launch its own satellites. That is something that Aschbacher has often called a “crisis” while emphasizing its temporary nature.

“If, for a couple of months, there’s not a rocket available, it’s bad enough. I’m the first one to call this a crisis,” he said at the “Investing in Space” conference by the Financial Times last month. “But this is not something permanent.”

The Falcon 9 carrying ESA’s Euclid on the launch pad several hours before its July 1 launch. (credit: J. Foust) |

Falcon to the rescue

The other launch that illustrated the current state of European space access took place four days and 4,000 kilometers from the final Ariane 5 flight. A Falcon 9 lifted off from Cape Canaveral July 1, much like dozens of other launches that SpaceX rocket has conducted so far this year. The big difference was its payload: a $1.5-billion space telescope—or, more precisely, a €1.4-billion European space telescope.

| “We were left completely in nowhere land, without any launcher,” said Racca. “It was an incredibly tense period because, in front of us, was the prospect of having to store the spacecraft for two years or more.” |

The Euclid spacecraft is a mission to study two of the biggest mysteries in cosmology: dark energy and dark matter, which combined comprise 95% of the universe. Equipped with a camera operating at visible wavelengths and a near-infrared spectrometer and photometer, astronomers will use Euclid to map a third of the sky, creating the most detailed 3-D map yet of the universe that can help them shed light on the nature of dark energy and dark matter.

“Euclid should provide a decisive response on the nature of dark energy,” said Yannick Mellier, an astronomer at the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris and leader of the Euclid Consortium, during a pre-launch press conference last month.

ESA had planned to launch Euclid to the Earth-Sun L-2 point on a Soyuz rocket, but when that rocket became unavailable last year, the agency had few options, particularly given the delays on the Ariane 6.

“We were left completely in nowhere land, without any launcher,” said Giuseppe Racca, Euclid project manager at ESA. “It was an incredibly tense period because, in front of us, was the prospect of having to store the spacecraft for two years or more.”

Last October, ESA announced it would instead launch Euclid on a Falcon 9. Euclid is not the first ESA mission to launch on a Falcon 9. Sentinel-6A, an Earth science spacecraft also known as Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich and developed in cooperation with NASA and other agencies in both the US and Europe, launched on a Falcon 9 in 2020. That launch, though, was provided by NASA as part of its contribution to the mission. In this case, ESA worked directly with SpaceX to arrange the launch of Euclid. (NASA is a partner on Euclid, providing infrared detectors for an instrument and hosting a data center, but was not involved in arranging the Falcon 9 launch.)

ESA officials said discussions with SpaceX started in May of last year, when a company executive told them they would have room on its manifest for Euclid in July of 2023. A three-month feasibility study followed to see if any changes were needed to the spacecraft because of the different launch environment of the Falcon 9, followed by tests to verify that assessment. “We can launch in July because did not have to change any of the hardware,” said Paolo Musi, Euclid program manager at Thales Alenia Space, the prime contractor for Euclid.

While ESA announced last October it would launch Euclid on a Falcon 9, the contract for that launch wasn’t finalized until late January. “We had to squash what we normally do in three years into five months,” said Mike Healy, head of science projects at ESA.

There was, he suggested, a bit of a culture clash between the Europeans and SpaceX. “There are too many differences to say,” he said. “They’re very can-do, can solve problems as we go along,” he said of SpaceX. “I think the European way is much more that we’ll optimize the process and make sure that we have to follow the process.”

“We had to adapt to each other. They were not used to us and we are not really used to them,” said Racca. “But I’m very happy with the relationship we had with SpaceX.”

There were technical challenges to overcome as well as regulatory ones. “The whole ITAR import-export control stuff is painful. That’s not SpaceX’s fault but that’s the reality,” Healy said. On past missions, like Sentinel-6, NASA handled that, but this time ESA and SpaceX had to grapple with those challenges. “But that’s just the environment that we face, and we managed to find solutions in a very short period of time to everything, so it can’t be that difficult.”

ESA officials declined to say how much they paid for the Falcon 9 launch, citing the commercial nature of the contract. Industry sources said that ESA paid a small premium over the list price of the Falcon 9, currently $67 million, to cover special mission requirements like enhanced cleanliness to avoid contamination of Euclid’s optics.

| “They’re very can-do, can solve problems as we go along,” Healy said of SpaceX. “I think the European way is much more that we’ll optimize the process and make sure that we have to follow the process.” |

Healy said ESA would do a more formal lessons-learned review after the launch, which will be useful since Euclid is not a one-off mission for the agency. When ESA announced last October it would launch Euclid on a Falcon 9, it also said it would move its Hera asteroid mission from an Ariane 6 to Falcon 9 to keep it on schedule for launch in October 2024. Hera will travel to the near Earth asteroid Didymos and its moon Dimorphos, which was the target for NASA’s DART mission last September.

At the ESA Council meeting last month, member states agreed to launch a third mission on Falcon 9. EarthCARE, an Earth science mission, was originally manifested on a Soyuz but moved last October to Vega C. Last December’s Vega C failure, along with changes in the design of the spacecraft itself, led ESA to switch the mission to a Falcon 9 launching in the second quarter of 2024.

Aschbacher said that the EarthCARE spacecraft’s dimensions had increased since the decision to move it to Vega C, which would have required modifications to the payload fairing of the rocket. The panel that investigated the Vega C failure recommended no changes in the configuration of the rocket through its initial launches. Given that assessment and the recent failure, ESA’s inspector general recommended not launching the mission on Vega C, he said.

Besides the ESA missions, there are also several Galileo spacecraft that need to launch next year that can no longer fly on Soyuz. At the ESA Council briefing, Javier Benedicto, ESA’s director of navigation, said discussions were underway with SpaceX for launching up to four Galileo satellites on Falcon 9 rockets, pending both technical analyses and the completion of a European Union security agreement.

The decision to launch Galileo satellites on Falcon 9 will be up to the EU, Aschbacher said, with ESA providing technical support. “We have provided all the technical information with regards to launcher compatibility, which the [European] Commission has,” he said after the Euclid launch. “Now it’s up to them to make a decision.”

While ESA’s near-term priority is getting Ariane 6 and Vega C flying, and relying on Falcon 9 in the interim, the agency sees the launcher crisis as an opportunity for longer-term changes in European space access. ESA is preparing for a European Space Summit in Seville, Spain, in November that will bring together both ESA and EU member states to discuss space priorities.

That will include proposals for a long-term space access strategy. “It’s really the larger picture of how Europe wants to establish itself in access to space,” Aschbacher said earlier this year. “It’s clear that the current situation needs a deeper reflection on the launcher sector in Europe.”

ESA hasn’t disclosed details of what might go into that strategy, but it will likely incorporate commercial developments in Europe as several companies work on small launch vehicles that have, so far, received only modest government support. Companies like Isar Aerospace and Rocket Factory Augsburg in Germany may be ready for their first launches before the end of the year, with other ventures also working on vehicles expects to fly in the next few years.

There is also the issue of looking beyond the Ariane 6 at what might follow. Europe developed Ariane 6 in part as a response to the rise of the Falcon 9, offering a vehicle that would be at least somewhat competitive in price. But Ariane 6 does not include any reusable elements—indeed, European officials often seemed skeptical about the benefits of reusability during the development of Ariane 6.

| “It’s clear that the current situation needs a deeper reflection on the launcher sector in Europe,” Aschbacher said earlier this year. |

But Falcon 9’s success in reusing boosters, enabling high flight rates and reduced costs, has prompted a reconsideration of the benefits of reusability. There have been some efforts to investigate reusability in Europe, including a methane-fueled reusable engine called Prometheus that underwent a static-fire test in June as part of a reusable stage demonstrator called Themis. But it’s unclear when, or how, that might translate into a vehicle with the kind of reuse that Falcon 9 demonstrates today, and other vehicles, like New Glenn, plan to offer in the next few years.

The near-term future of Ariane 6 is secure: once the vehicle does start flying, its manifest is full for a few years with European government missions as well as a large order from Amazon’s Project Kuiper constellation. What happens after that, though, is less clear.

“We are in a crisis and we should use the opportunity to convert this crisis into actions and changes that need to be adopted in order, in the future, to develop a robust launcher system for Europe,” Aschbacher said after the launch of Euclid, but was convinced the current crisis—a lack of any ability for Europe to launch payloads—will soon pass. “Then this few months will be a blip.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.