For Mars Sample Return, more serious repercussionsby Jeff Foust

|

| “If NASA is unable to provide the Committee with a MSR lifecycle cost profile within the $5,300,000,000 budget profile, NASA is directed to either provide options to de-scope or rework MSR or face mission cancellation,” the Senate report stated. |

As part of the festivities, the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) announced the presentation of two “Champions for Astronomy” awards. The recipients were not astronomers, engineers, or program managers, but instead two senators: Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) and Jerry Moran (R-KS). They were recognized, said Maura Hagan, chair of AURA’s board of directors, for their role in keeping JWST on track when it ran into problems late in its development, causing it to break an $8 billion cost cap that had been established years earlier when JWST had another near-death experience in its development. Back then, Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) helped engineer that deal that kept JWST with that cost cap, but she had retired before the problems that caused the cost cap breach.

Shaheen and Moran, the chair and ranking member of the commerce, justice, and science (CJS) appropriations subcommittee that funds NASA, “could have kept the cap in place and walked away, leaving JWST a total loss,” Hagan said. Instead, they worked with NASA to analyze the problems and established a new cost cap of $8.8 billion that held through the launch. “They gave JWST a lifeline.”

The award ceremony—which neither Shaheen nor Moran could attend—took place hours after those senators offered something far less than a lifeline for another major NASA science mission. Earlier in the day, the Senate Appropriations Committee approved a CJS spending bill for fiscal year 2024 that provided $25.0 billion for NASA. That was far short of the $27.2 billion NASA requested and even the $25.4 billion the agency received in 2023.

The funding decrease was not a surprise given a debt-ceiling deal Congress and the White House reached at the end of May that capped non-defense discretionary spending at 2023 levels (see “A chaotic trajectory for NASA’s budget”, The Space Review, June 19, 2023). That would inevitably lead to tough decisions about funding for science, exploration, and other programs.

What was surprising, though, was the language included in the report accompanying the bill regarding Mars Sample Return (MSR). The committee effectively put NASA on notice to keep the program’s cost under control or face cancellation.

Despite providing $1.74 billion to MSR through 2023, the report stated, “the expected launch schedule continues to slip and the increasing fiscal and human resources devoted to MSR is causing NASA to delay other high priority missions across the Science Mission Directorate.”

“The Committee has significant concerns about the technical challenges facing MSR and potential further impacts on confirmed missions, even before MSR has completed preliminary design review,” it added, noting that NASA has not yet set a formal cost and schedule for the program, a milestone expected this fall.

The committee directed NASA to submit year-by-year budget profile for MSR with a total cost of no more than $5.3 billion, the recommendation from last year’s planetary science decadal survey. “If NASA is unable to provide the Committee with a MSR lifecycle cost profile within the $5,300,000,000 budget profile, NASA is directed to either provide options to de-scope or rework MSR or face mission cancellation.”

| “They will have significant challenges in continuing all of their programs. I’m disappointed by that,” Moran said of NASA funding in the bill. “NASA will have a lot of work to do to figure out how to continue on the programs they are currently planning.” |

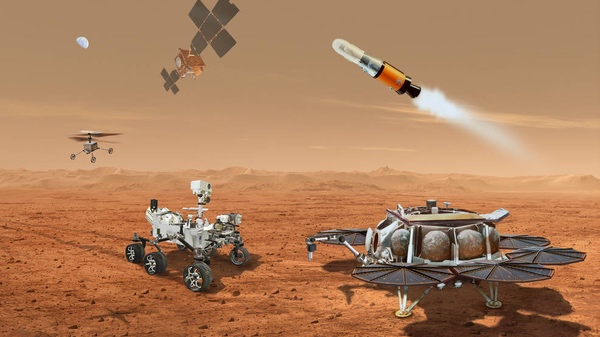

It appears unlikely that NASA would be able to significantly rework or descope MSR. In recent presentations, agency officials have said that the only descope option for the program that would still allow it to achieve its primary goal of returning samples cached by the Perseverance rover to Earth would be to remove one of two small helicopters, modeled on Ingenuity, from the Sample Retrieval Lander. Those helicopters are themselves backups if Perseverance is unable to return to the lander; the helicopters would pick up a set of ten sample tubes left on the surface by the rover early this year.

“There are not really any significant descopes available to us here,” Jeff Gramling, MSR program director at NASA Headquarters, told members of two National Academies committees at a June 7 meeting.

If NASA was forced to cancel MSR, the committee’s report even spelled out how the funding that it did provide to the program would be reallocated: $235 million for Artemis Campaign Development, $30 million each for the Dragonfly mission to Titan and the Geospace Dynamics Constellation heliophysics mission, and $5 million to begin studies for a planetary science flagship mission to Uranus recommended by the decadal survey.

That was the other surprise about the Senate bill: it offered only $300 million for MSR, less than a third of the nearly $950 million requested by NASA for 2024. Even that amount might not have been sufficient: the program needed an additional $250 million on top of the request in 2024, NASA administrator told Senate appropriators at a hearing in March.

It is tempting to blame the Senate’s language about MSR on the budget caps imposed by the debt-ceiling agreement. Cutting more than $2 billion from NASA’s budget proposal meant a lot of hard decisions. “They will have significant challenges in continuing all of their programs. I’m disappointed by that,” Moran said of NASA during the appropriations markup, calling the cuts “inevitable” because of the debt-ceiling deal. “NASA will have a lot of work to do to figure out how to continue on the programs they are currently planning.”

But the challenges facing MSR are so serious that Senate appropriators might still have acted even if the agency’s budget proposal could be fully funded. Nelson’s comments in April about the need for an additional $250 million only heightened concerns about the status of MSR as it heads into a confirmation review this fall that will set its formal cost and schedule.

NASA officials have refrained from offering any cost estimates for MSR in recent months. Other than the $5.3 billion cap in the decadal survey, the only other recent estimate came from an independent review in 2020 that estimated the cost at between $3.8 billion and $4.4 billion, which itself was a significant increase.

A report last month, though, claimed that one updated cost estimate developed at JPL for MSR came in at between $8 billion and $9 billion, an increase that took nearly everyone in the Mars science community by surprise. MSR would end up costing as much as JWST if that figure held up.

NASA confirmed, with caveats, that estimate in a June 26 statement. “NASA evaluates a wide range of funding scenarios every year for its portfolio of missions as part of its annual budget process. Missions in formulation, such as Mars Sample Return, have more variables to consider, providing for a greater range of scenarios to evaluate—all scenarios are highly speculative,” the agency stated. “One included a lifecycle cost range of $8–9 billion, which included launch, operation, and closeout cost estimates.”

| “I get it that everybody is anxious about this. We’re all anxious about it,” said Glaze of MSR funding issues. |

Even with that “highly speculative” disclaimer, the statement only added to the angst that had been building about MSR. Several days earlier, NASA’s Planetary Science Advisory Committee (PAC) debated the program and concerns that its cost growth could eat into budgets of other planetary programs.

“I get it that everybody is anxious about this. We’re all anxious about it,” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, of MSR at the PAC meeting.

In the meantime, NASA is performing a second independent review of MSR, a rare measure for a program at this early phase of development. That review is chaired by Orlando Figueroa, a former director of NASA’s Mars exploration program, and will conclude in time for its recommendations to feed into the confirmation review this fall.

We’re taking this very seriously and we’re trying to make sure we have solid plans before we go to confirmation,” Gramling said of that second independent review at the National Academies meeting. “We’re taking a very deliberate approach to confirmation. We’re trying to go back and make sure that we’ve put scrutiny on all of our technical plans and we’ve gotten scrutiny on the associated cost and schedule.”

There is no guarantee that the Senate language about MSR and funding levels will make it into a final appropriations bill (if there is a final bill; with a divided Congress there are concerns about a year-long continuing resolution or even a government shutdown.) The House CJS appropriations subcommittee marked up their spending bill on Friday, but released few details about it, including any provisions about MSR. Overall NASA science funding in the House bill is about the same as the Senate bill, but with no information about how that is allocated among the agency’s programs.

It's possible, then, that the threat of cancelling MSR in the Senate bill will be seen as a warning shot to NASA to get the program in order and make tough decisions about how and when to conduct it. If successful, then, that action might indeed become a lifeline of sorts to MSR, in much the same way as the threat of cancelling JWST more than a decade ago refocused that program towards its ultimate success. The senators that won the “Champions for Astronomy” awards last week might be in line for another award in a decade or so if MSR follows that trajectory.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.