An extended mission for authorizationby Jeff Foust

|

| The House bill “crafts a favorable and competitive environment right here at home by streamlining our regulatory process and clarifying federal roles in licensing commercial space activities,” Lucas said. |

Some would argue that there is no need for another regulator, creating a bureaucracy that would only slow down companies. However, the Outer Space Treaty requires signatories to provide “authorization and continuing supervision” of space activities by non-state actors under its jurisdiction. As the number of new space activities grows, one-off solutions to the issue become less viable for industry and government alike.

So, since the Obama Administration, there has been ongoing debate and discussion about what agency would take on that “mission authorization” responsibility, and how they would do it. That debate has usually revolved around two agencies, the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation, or AST, within the Department of Transportation, and the Office of Space Commerce, part of NOAA within the Department of Commerce. Last September, Vice President Kamala Harris said at a National Space Council meeting that she wanted to see proposals for mission authorization concepts within 180 days (see “The debate about who should regulate new commercial space activities”, The Space Review, October 31, 2022.)

That debate has resulted, in recent weeks, in both a White House proposal for mission authorization as well as House legislation. However, those milestones show that industry and the government may be no closer to resolving this longstanding issue.

The House publicly moved first on the issue, with the introduction November 2 of the Commercial Space Act of 2023 by Reps. Frank Lucas (R-OK) and Brian Babin (R-TX), the chairs of the House Science Committee and its space subcommittee. A key element of the bill would be to create what it called a “certification” process that would be its version of mission authorization.

Under the bill, responsibility for certification of commercial spacecraft would lie with the Office of Space Commerce. Companies seeking certification—not required if they are already licensed by the FCC or FAA—would have to provide basic information about their spacecraft, a space debris mitigation plan, and miscellaneous other information, such as an attestation that the spacecraft is not a weapon. The Office of Space Commerce would then have 60 days to review the application, with a presumption of approval: the certification would be granted at the end of that 60-day period unless explicitly denied.

“This bill crafts a favorable and competitive environment right here at home by streamlining our regulatory process and clarifying federal roles in licensing commercial space activities,” Lucas said in the statement about the bill.

The White House responded with its own proposal November 15. The National Space Council released a legislative proposal—a draft bill—that outlined its own approach to mission authorization. Notably, given a choice between giving mission authorization responsibility to the Commerce Department or the Transportation Department, it chose both.

| “The Space Council proposal may or may not be the vehicle we want to move forward,” Lofgren said. “I think ignoring their work would be a mistake.” |

The White House proposal decided to split mission authorization responsibilities between FAA/AST and the Office of Space Commerce. FAA would handle any in-space activities involving human spaceflight, extending its role in regulation crewed launches and reentries. It would also handle any activities that solely involved the in-space transportation of items through space, including to the lunar surface. The Office of Space Commerce would handle all other uncrewed space activities not otherwise licensed already.

Leaders of the two departments offered their public support to the proposal. “The FAA remains committed to ensuring novel in-space activities occur safely and efficiently. We look forward to supporting an all-of-government approach working with industry,” said Polly Trottenberg, deputy secretary of transportation, in a statement.

“This legislation ensures that our government will build a regulatory environment that supports commercial expansion to benefit all Americans,” said Don Graves, deputy secretary of commerce.

The timing of the proposal’s release by the White House raised more than a few eyebrows: it came out less than an hour before the House Science Committee held a markup session to consider its Commercial Space Act.

That helped turn the markup into a partisan debate about the bill and the White House proposal. “These proposals, I fear, simply go in the wrong direction and hurt rather than support America’s space industry,” Lucas said of the White House’s approach to mission authorization, calling it a “needless expansion of government authority.”

Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), ranking member of the committee, called for a delay in the consideration of the House bill until members could fully review the proposal. “The Space Council proposal may or may not be the vehicle we want to move forward,” she said. “I think ignoring their work would be a mistake.”

The committee did delay a vote on the bill by two weeks, but in the end passed the bill on a party-line vote. Lofgren said that while she continued to have reservations about the bill—which extend to provisions not related to mission authorization, such as its approach to space traffic coordination—she hoped “to work with the majority between now and the floor so all of us can be confident that this is the consensus of where we should move.”

That vote came just after an industry group weighed in against the National Space Council proposal. In a letter to the House Science Committee and the Senate Commerce Committee, the Commercial Spaceflight Federation (CSF) argued the administration’s proposal ignored advice that it received from industry in “listening sessions” held last year to collect input on mission authorization.

“For some operations, it is unclear which agency would hold the authority to issue a relevant license, or if multiple licenses would be needed,” the CSF stated in its letter, adding it was particularly concerned it could result in a “bifurcated and unclear regulatory regime for commercial space stations.”

The letter endorsed an approach more like the House bill, giving mission authorization to the Office of Space Commerce under an approach that included a presumption of approval and firm timelines to review applications.

The National Space Council’s own advisory group offered a similar view. At a meeting of the Users’ Advisory Group (UAG) December 1, the group’s economic development and industrial base committee offered a dozen recommendation for mission authorization. They included a presumption of approval, strict review timelines, and having the process handled by one agency “to minimize confusion and compliance burden,” according to a presentation at the meeting.

“I don’t see any fundamental differences, if you will, between the recommendations that are captured here” and the White House proposal, said the chair of the UAG, Lester Lyles. “There may be some semantic differences, but I don’t see any fundamental differences.”

| The White House proposal “contains numerous ambiguities, new undefined terms, and broad grants of open-ended authority,” Sinema said. |

The chair of the UAG subcommittee, Eric Fanning, corrected him. “There are some disconnects between what the House is doing, what the Senate is doing, what the White House has proposed, and the recommendations of this subcommittee,” he said.

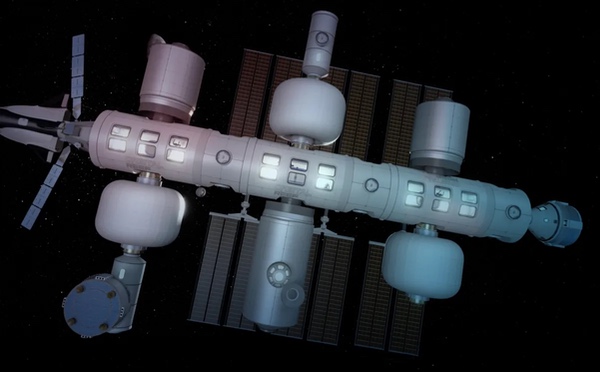

Officials from NASA, FAA, Office of Space Commerce, and the Defense Department offered their support for the White House’s mission authorization proposal at a December 13 Senate hearing. (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) |

The Senate, working on its own commercial space bill, has not released details about how it might approach mission authorization. But at a December 13 hearing by the Senate Commerce Committee’s space subcommittee, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (I-AZ), chair of the subcommittee, said she had issues with the White House’s proposal.

“I am heartened that the administration is working on this critical issue, but the proposal contains numerous ambiguities, new undefined terms, and broad grants of open-ended authority,” she said. She did not go into specifics, though, and left the hearing during opening statements by the witnesses, not returning to question them on mission authorization or other topics.

Those witnesses, from NASA, FAA/AST, Office of Space Commerce, and the Defense Department, endorsed the White House approach. (The National Space Council was invited to participate, Sinema said, but declined.) They argued that mission authorization was both necessary and, as proposed, would not be a burden on companies.

“As NASA is increasingly a customer for commercial services, we really need greater clarity regarding who is responsible for authorizing and supervising commercial space activities,” said NASA deputy administrator Pam Melroy, saying the agency was pleased with the National Space Council’s proposal. “The intent of this supervision is not to stifle or slow down industry but rather to work with industry in advancing commercial space.”

John Hill, deputy assistant secretary of defense for space and missile defense, said the Pentagon was not interested in being a regulator, but wanted to work with other agencies to ensure regulations reflected up-to-date national security concerns (an issue that was long a problem for the commercial remote sensing industry as it pushed to get licenses for more advanced imaging systems.)

The White House’s mission authorization proposal requires interagency consultation for national security, he said, “and to be very clear, often the overriding national security consideration is to enable competitiveness of US industry without burdensome licensing conditions.”

At one point in the hearing, Sen. J.D. Vance (R-OH) quizzed the witnesses on hypothetical scenarios to illustrate potential flaws in the White House proposal. Who would be responsible, he asked, if an in-orbit servicing vehicle—something Commerce would authorize in the White House plan—docked with a commercial space station?

Richard DalBello, director of the Office of Space Commerce, explained that the two vehicles would have separate authorizations, and that the agencies would coordinate in any scenarios where there might be uncertainty about who is responsible: “Where there is a jump ball, there will be an interagency discussion.”

Kelvin Coleman, FAA associate administrator for commercial space transportation, also emphasized that the office would take a “light touch” approach to mission authorization, particularly when compared to the more rigorous launch licensing approach driven by requirements to protect the uninvolved public. Some in industry have worried about giving FAA/AST, which has a full plate already with launch and reentry licensing, even more work.

“Launch licensing is an intense process,” he said, but mission authorization need not be as rigorous because of the far lower risk of in-space activities on the safety of the general public. “We envision a very light-touch approach.”

| Getting any commercial space bill through Congress by the end of 2024 will likely require expedited procedures like suspension of the rules in the House and unanimous consent in the Senate. |

That hearing represented the strongest defense to date of the White House’s proposal. More could come on Wednesday when the National Space Council holds its first public meeting since the September 2022 event where Vice President Harris called for mission authorization proposals from agencies. The theme of the hearing is on international partnerships, but some in industry expect discussion on mission authorization, possibly including a policy on the issue separate from the legislative proposal.

However, with wide gaps among proposals from the National Space Council, the House, and perhaps the Senate, there may not be a resolution to mission authorization in the foreseeable future. Getting any commercial space bill through Congress by the end of 2024 will likely require expedited procedures like suspension of the rules in the House, requiring two-thirds approval, and unanimous consent in the Senate, which allows for passage without debate if no senators object.

Unless existing differences can be bridged in the next year, advocates for mission authorization may need to start over with a new Congress, and possibly a new administration, in 2025, continuing a long-running debate.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.