Risk management: our daily game of Russian Rouletteby Eric R. Hedman

|

| We make these decisions as to what is an acceptable risk based upon our observations, experience, deductions, intuition, and emotions. |

A couple of years ago I ran into a schoolmate I hadn’t seen since high school. As we were talking he told me that only a few hours prior he had stepped off an airplane from China. It was at the peak of the SARS outbreak in Asia. He had just spent nine months touring all corners of China performing his magic act for literally millions of people. He said when he was in the airport in Beijing, nobody leaving the country dared to even sneeze because they would have been immediately hauled off to quarantine. As I was standing a few feet away from a guy I was laughing and joking with, it crossed my mind that there was a slight possibility that he was exhaling a potentially lethal pathogen. Two of my grandparents had survived the Spanish flu in 1918.

Sometimes people are not very good at risk management. We can make very bad decisions based on faulty reasoning. Take for instance the complacency that safety features can instill in people. I know people that stopped using safety belts when they started purchasing vehicles with airbags. People that drive SUVs tend to think the sheer mass and high vantage point give them command of the road and greater safety. They ignore, or are unaware of, the effects a higher center of gravity has on vehicle stability, as well as the effect mass has on the kinetic energy that is dissipated in a crash. One of my brother’s neighbors got a close-up lesson when an SUV ahead of him on the freeway swerved to avoid something on the road. It seemed to recover and then rolled violently several times, demolishing the vehicle before coming to a halt.

Sometimes denial is a key factor in bad risk management. How often have you heard on the news when something bad happens in a quote safe neighborhood or small town, “I never thought something like that could happen here?” Another prime example is building in areas where massive natural disasters are possible like New Orleans. New Orleans is not alone. Massive tsunamis have hit the Pacific Northwest coast roughly every three hundred years since the last ice age, caused by earthquakes in the offshore subduction zone. The last one hit in 1700. You do the math. Los Angeles and San Francisco will both eventually be hit by the next “Big One.” I have no illusions that people and the government will remember many of the lessons of Katrina and Rita for more than a few years.

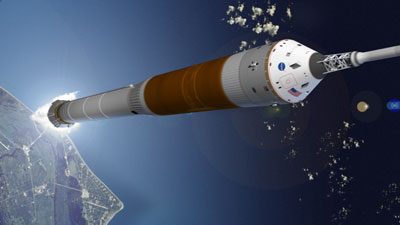

Why am I writing about human behavior and risk management? During NASA’s presentation of the new architecture for the Crew Exploration Vehicle and the new heavy-lift launch vehicle, officials stated that the new vehicles would have a tenfold improvement over the shuttle in safety, to one chance of a catastrophic failure for every two thousand launches. It reminded me of Captain Kirk asking Spock what there odds were of getting out of a tough situation, trapped on an alien planet with hostile forces all around. Mr. Spock would come up with something like one in five thousand four hundred sixty three. In both cases the numbers were ridiculous and meaningless. They are meaningless because they are based on just the known, or perceived to be known, factors. They ignore the fact that with complex systems and difficult, minimally-explored operating environments, there are always unknown factors.

In hindsight, before the Challenger disaster the people running the shuttle program seemed to be giving lip service to the dangers involved. The fact that they discounted the warning about the risk of O-ring failure with a cold weather launch proved it. With so many NASA employees having once taken a basic physics class, the fact that falling debris was assumed not to be a threat because it was made out of foam is disturbing. Anyone who has ever fired a high-powered rifle at a target like an old paint can filled with water knows the devastating impact of a projectile with a mass of less than an ounce moving at that speed. Likewise, they should have intuitively known that a 760-gram chunk of foam hitting the wing of Columbia would pose a major risk.

| When NASA puts a specific risk probability number on a vehicle that is far from design completion, I don’t like it. You would think that NASA would have learned not to put out numbers that the press obviously wants but are meaningless. |

The human race has very little experience traveling to the Moon. There have only been six successful landings. Before the first mission launches to return to the Moon, there will be countless experts trying to anticipate and understand the dangers, just as there were before the first launches in the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Shuttle programs. There are still unknown and presently unquantifiable risk factors in flying to the Moon. How much warning will there be before a massive solar flare heads this way with astronauts outbound toward the Moon? We’ve recently had an unusual number of solar flares during the solar minimum. How bad will lunar dust foul hatches, equipment, and human lungs? What factors will the experts miss?

The design of the Crew Exploration Vehicle removes two of the greatest dangers involved in shuttle launches. Lifting the crew capsule above the booster protects it from falling debris, and the CEV will also no longer have as an incredibly fragile a heat shield as the shuttle. Lifting the capsule above the booster doesn’t eliminate the threat of an object strike: the shuttle on its return to flight struck and killed an albatross as it was lifting clear of the tower. Fortunately for the crew, the strike was on the external tank and not on the orbiter’s belly. If it had happened at a higher altitude when the vehicle is moving faster and struck the nose or the belly of the orbiter, the albatross is more massive than the foam that hit Columbia’s wing. Its beak is also much harder than foam. Bird strikes have taken down more than their share of airplanes over the last century.

When NASA puts a specific risk probability number on a vehicle that is far from design completion, I don’t like it. It is like Mr. Spock giving Captain Kirk exact odds on success when he only knows a fraction of the variables. I would have thought that somebody as smart as Spock would have learned that his astronomical odds against success were meaningless after they beat them time and time again. (Yes, I do know it was only a TV show before you write me about it.) You would think that NASA would have learned not to put out numbers that the press obviously wants but are meaningless. What I would like to have heard from NASA is a statement about safety that said they are removing as many of the risks in spaceflight as they can reasonably do. I wanted to hear that safety is a constant concern and that they will do their best not to let their guard down. I wanted to hear that they think the new design is safer and that they will have a program in place to constantly assess and reduce the risks. That would tell me that they are not already getting complacent and arrogant enough to think that they have everything figured out. Don’t get me wrong: I like the new plans, and I also am not paranoid about danger. I, like most people, have taken some dumb risks. I just think that vigilance is important, especially in a program as expensive, risky, and needed as I think this one is.