Columbia retold, and untoldby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The stories of the families were emotional and often heart-wrenching. Husbands lost wives, wives lost husbands, and young children lost their parents. |

There are many ways to tell a story in a documentary. Should it have a narrator? Should it just let the interview subjects talk? Should it focus on dates and details, or emotions? Who should be interviewed and how should they be presented? Space Shuttle Columbia, the Final Flight was not hyperbolic or overly dramatic. The producers treated their subject with respect. But they chose to lean more heavily on the emotional and human elements and less on technical details, policy decisions, and NASA’s flawed culture. By doing so, they created a false impression of what happened after the accident occurred, and why that was important.

The documentary’s first episode covered the months leading up to the January 16th launch and the second episode primarily covered the mission itself. The third and fourth episodes dealt with the accident and the investigation. All featured interviews with people involved in the mission as well as some families of the seven astronauts who died on February 1, 2003, due to damage suffered during launch two weeks earlier. The stories of the families were emotional and often heart-wrenching. Husbands lost wives, wives lost husbands, and young children lost their parents. Having to re-live that time was undoubtedly difficult for them, but it brought a poignancy to the documentary that was valuable.

The show devoted limited attention to NASA’s senior leadership at the time, failing to ask the question of how much they knew about the contributing factors to the accident. The producers interviewed NASA personnel who were involved in the mission, some of whom had raised alarms about the early indications that foam had come off the shuttle’s external tank and struck the orbiter, only to be told to stop their inquiries and let the issue go. Several episodes devoted substantial time to these topics and how the cause of the accident was uncovered in the months after it occurred, but they left out important details.

What was most missing from the documentary was a discussion of the actual accident investigation and the people who performed it. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) was established within hours of the accident, and grew rapidly, adding board members and investigators with necessary expertise. (I was hired as an investigator by April, at a point when the number of investigators, which peaked at over 100, was beginning to decrease as data collection was transitioning to data analysis.)

The CAIB also evolved. Initially it was technically under NASA. But the board chair, retired Admiral Hal Gehman, realized that for the CAIB (pronounced “kaabe”) to be credible, it had to both be independent and perceived to be independent by Congress, the White House, the media, and the public. Gehman and his board members took actions to make that happen, initially by removing some NASA personnel from the investigation, and then by constantly communicating that the investigation was independent of NASA. There were some bumps along the road as NASA officials realized the CAIB was truly independent, but as far as we could tell, those officials did not seek to impede the investigation. There was a parallel NASA effort that supported the CAIB in the form of collecting shuttle debris and reassembling it, and gathering data that was made available to the CAIB.

Surprisingly, the CAIB is barely mentioned at all in Space Shuttle Columbia, the Final Flight, and only one board member was interviewed. According to another board member I spoke to, the documentary had planned to interview other board members and perhaps devote an entire episode to the investigation but lacked the funds to do so. Thus, the documentary discusses the accident investigation without identifying the organization and people who undertook it, how they did their jobs, and the impact they had on subsequent policy decisions.

| A bigger problem of not devoting significant attention to the CAIB is that the documentary missed a lot of the context and the culture of the investigation. |

The omission of the CAIB story from the documentary has several effects. For starters, the documentary includes interviews with several NASA engineers involved in assessing the launch footage and then attempting to estimate possible damage to the orbiter. This happened within NASA during the mission, but information about it was only uncovered and investigated—and made public—by the CAIB after the accident. Without explicitly stating this, the documentary created the impression that NASA was responsible for investigating itself and somehow this information came to light on its own. One of my colleagues on the CAIB was an aircraft accident investigator who was charged with reviewing tens of thousands of internal NASA emails, which helped expose how the effort to obtain better imagery of the damaged orbiter was suppressed within the program. Understanding this is important because of the contrast between the CAIB and the 1986 Challenger accident investigation. That earlier investigation was less independent of NASA, a fact that undercut its credibility. Admiral Gehman had deliberately sought to avoid the mistakes of the Challenger investigation.

Perhaps a bigger problem of not devoting significant attention to the CAIB is that the documentary missed a lot of the context and the culture of the investigation. As former CAIB board member Scott Hubbard has noted, human spaceflight at that time was a very hierarchical operation, with deep roots in military culture, with orders coming from on high. It was also very procedures-based. Things outside of normal procedures, like seeking new data on the debris strike, could be shut down by orders from senior personnel in the shuttle program. The documentary notes this but fails to explain that it then took the CAIB to force the story of the suppression of data-gathering, and answers about why it happened, out of the shuttle program. The CAIB was also necessary to force people within the program to realize the problems. Without the investigation, those details may never have become publicly known, and a major change in NASA’s safety culture would have been less likely.

The investigation was methodical and comprehensive, going beyond the technical explanation for the accident to explore the policy, budgetary, social, and cultural factors that may have made it possible. Sometimes it explored dead ends. Sometimes the CAIB investigators pursued leads simply to rule them out as causes of the accident (I personally read thousands of pages of investigation interviews looking for items of interest for one part of the investigation but never found any.) Inside the CAIB there were discussions of fault trees and NASA engineering culture and even the dangers of jargon. NASA engineers commonly referred to data being “in family” or “out of family,” which essentially meant that the data was expected or unexpected. We in the CAIB noticed that these terms were used sloppily and inconsistently, but it was not our job to tell NASA what language to use in their program.

We looked at other subjects outside of NASA like naval nuclear reactors, large chemical manufacturing facilities, and even aircraft carrier operations, for what they indicated about organizations that could not tolerate mistakes because the consequences could be catastrophic. The CAIB also explored NASA’s policy changes and budgets over the previous decade to determine if they contributed to the accident. We dug into NASA administrators’ files and budget documents. We delved into subjects like the 1990s-era Space Flight Operations Contract, which reorganized how the shuttle program was managed, looking for clues to later program and budget decisions. We could find no obvious direct link but ran down many leads. It was a massive, multi-faceted, detective project. We kept a big photograph of the STS-107 crew on the wall of our main meeting room to remind us to work hard to honor them.

| The RCC test, which was publicly reported at the time, changed the attitude of the NASA shuttle engineers. At least several were shocked, but from that point on nobody could deny that foam could cause major damage to the orbiter. |

The CAIB members and investigators also began to notice disturbing attitudes within the shuttle program. What had initially started as a safety edict in the shuttle program—foam shall not hit the orbiter during launch—had evolved into a maintenance issue: how long will it take to repair foam damage to the orbiter? There was a lack of curiosity within the program when the shuttle did not perform the way it was supposed to. NASA engineers tended to look at unusual events in terms of their effect on operations and schedules rather than asking why they were happening. And once an anomaly was dismissed as a risk, people might even become defensive about it. I distinctly remember one NASA shuttle tile expert, one of the people who had developed them in the early 1970s, who was full of blustery confidence about how shuttle tiles were tough and not easily damaged. He was not merely being defensive: he was clearly not interested in how they could be damaged. That attitude was a warning sign, an indication of how much some NASA personnel were stuck in their thinking.

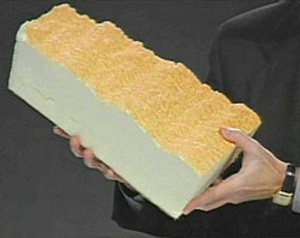

A piece of from from the shuttle's external tank approximately the size and mass of the piece that came off the tank and struck the orbiter. The foam essentially came off the tank and stopped, and the orbiter ran into it at high velocity. The physics of such an impact is relatively simple, and devastating for the orbiter. The psychology of that impact was far more complicated, and even very smart engineers had a hard time accepting that foam could cause damage. (credit: NASA) |

The documentary’s fourth episode includes a brief clip about the test on the ground in the summer of 2003 where a piece of foam was shot at an actual piece of flight hardware, a leading edge of the orbiter’s wing. That test blew a hole through the reinforced carbon carbon (RCC) wing segment, making clear that foam could cause tremendous damage to the wing. Left out of the episode was the background story of that test.

The dramatic test shown in the documentary, which was conducted at a facility in San Antonio, Texas, was only the last in a series. There were about a half dozen earlier tests, which are only briefly mentioned in the final report. I witnessed one of them. The air cannon used to launch the foam was the same one used to launch dead chickens at airplane cockpits to test their survivability against bird strikes. (During my visit we asked about the myth of using frozen chickens and were shown the bucket used to euthanize live chickens by exposing them to—I think—carbon dioxide gas.) The foam strike tests evolved over time. Early in the investigation one theory was that the foam struck the underside of the orbiter at a shallow angle. The CAIB ordered that one of the landing gear doors from the unflown space shuttle Enterprise be removed from that vehicle, covered with actual tiles, and then hit with foam. Later, when that door was re-installed on Enterprise, it still bore the scars from the test.

As more accident data was acquired, the investigation shifted focus to a strike on the RCC panels on the leading edge of the wing. This presented a dilemma that was more about psychology than engineering. When accelerated to hundreds of kilometers an hour, a kilogram of foam has the same energy as a kilogram of steel. The physics equation should have been readily understandable to the engineers of the shuttle program. RCC is tough material, heavy and dense. I handled a piece and it felt like a combination of steel and ceramic, and I figured I could drop it on a concrete floor and it would be undamaged, or drop it on my foot and break a toe. The CAIB was telling NASA’s shuttle engineers that foam had damaged the RCC, and showing them the physics equation, but the engineers did not believe that low density foam could harm high density RCC.

Before the CAIB ordered a test of foam against actual RCC, they did a “clocking test,” firing foam at some plastic mockup RCC panels also removed from Enterprise. This test was intended to determine the right angle to mount the RCC for an actual test, not simulate the actual impact. But when the foam only scuffed the plastic RCC panels, we heard some people suggest that it was “proof” that foam could not damage the RCC.

The CAIB wanted a test against an actual RCC panel, but NASA officials resisted. NASA did not have many spare RCC panels, they were very expensive (I seem to remember that a single panel cost $750,000), and they took most of a year to manufacture. Was the test really necessary, some NASA shuttle officials asked? The CAIB decided it was necessary.

I was working in the CAIB’s offices outside of Washington when we heard about the results of the test in San Antonio, that it had blown a hole through the RCC approximately 41 centimeters in diameter. Such a hole was easily large enough to allow plasma during reentry to enter the wing, and the high temperatures compromised its structural integrity until it broke off and the orbiter rapidly came apart at hypersonic speed. The hole in the leading edge was consistent with all the sensor data collected as the wing failed.

| Perhaps the most important role of the CAIB was in ending the shuttle program, and ultimately changing the way that the United States sent people into space. |

The RCC test, which was publicly reported at the time, changed the attitude of the NASA shuttle engineers. At least several were shocked, but from that point on nobody could deny that foam could cause major damage to the orbiter. Space Shuttle Columbia, the Final Flight showed the dramatic last foam test, but missed the detective story of the investigation. The documentary also missed the cultural and psychological shifts within the shuttle program forced upon the engineers by the RCC test. Certainly the accident itself caused some people to change their attitudes, but it was the investigation that pushed others past the denial phase to start accepting responsibility.

The hole blown in a piece of reinforced carbon carbon (RCC) the covered the leading edge of a space shuttle wing. NASA officials resisted this test, but the Columbia Accident Investigation Board ordered that it be conducted, in large part because people within NASA still did not believe that low density foam could damage high density RCC. (credit: NASA) |

During the investigation, we began to realize that NASA’s shuttle program was an insular and incurious organization that did not study or learn from accidents in other high-technology fields, and not even its own. One of the things that we at the CAIB discovered was that before Columbia, NASA neither studied nor taught the lessons of the 1986 Challenger accident. Other than an annual day of remembrance, they treated it as if it was simply a dark time in the distant past that they wanted to forget, not a warning for the present. I was one of the people who urged Diane Vaughn, author of a detailed study of the Challenger accident, to publicly state that she had never been invited to NASA after the 1996 publication of her book. The day after we got her to say that during a press conference, she was invited to visit the NASA administrator, a small example of forcing the organization to change its attitudes.

But perhaps the most important role of the CAIB was in ending the shuttle program, and ultimately changing the way that the United States sent people into space. Inside the CAIB we developed a timeline of major shuttle program decisions, including all the times after Challenger that NASA planned to retire the shuttle only to reverse course after the replacement costs grew too high. It was clear that NASA was likely to continue flying the shuttle for many years unless it was forced to stop, possibly by the next accident. The CAIB did not recommend an immediate end to the program but did recommend actions that would make it difficult to continue flying the shuttle beyond a few more years.

It was the CAIB that forced important and embarrassing information out of NASA, the CAIB that ordered the test that removed any remaining doubt or denial about the technical cause of the accident, and the CAIB that started the clock ticking to end the shuttle program. Those facts are important in any account of the Columbia accident and its aftermath.

The documentary’s final episode devoted a few minutes to claiming that NASA has learned, and now teaches, the lessons of the Columbia accident, but did not explore how the agency does so, particularly in an era where it has contracted out astronaut launches to private industry. That subject alone could probably be the focus of an entire documentary, because lessons must constantly be learned and relearned, and taught to the new employees who may not have been born when the last accident occurred. Space Shuttle Columbia, the Final Flight is not the final story. There is more to be told. There always will be.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.