Star-crossed linerby Jeff Foust

|

| “We’ve done everything that we can to make sure that we’re not missing things,” said NASA’s Stich in March. |

The trials and tribulations of Starliner have been clear for years, but earlier this spring both Boeing and NASA said they had put those problems—such as faulty software, corroded valves, flammable tape wiring, and inadequate parachute components—behind them. Starliner was finally ready for the Crew Flight Test (CFT) mission, a test flight to show that the spacecraft can safely transport astronauts to and from the station.

Both the agency and company believed those problems were behind the program. “We have very robust processes,” said Mark Nappi, the Boeing vice president who is program manager for commercial crew at the company, at a briefing in March. “The proof of that is that the problems that we have caught in the past have been caught as part of that process—albeit they have been caught late.” He cited as proof of that the “exceptionally successful” second uncrewed test flight of Starliner in May 2022.

“We’ve done everything that we can to make sure that we’re not missing things,” said Steve Stich, NASA commercial crew program manager, at that same briefing.

But when they proceeded with a launch attempt for the CFT mission May 6, what tripped them up was not the spacecraft but the rocket. Two hours before liftoff, with Wilmore and Williams in the process of boarding Starliner, managers scrubbed the launch: an oxygen relief valve in the rocket’s Centaur upper stage was oscillating, vibrating at 40 hertz.

Resetting the valve would solve the problem, which had been seen a few times in past Atlas launches, but doing so would violate flight rules put into place for CFT, the first crewed Atlas 5 launch, that prohibit changes to the state of the Centaur once loaded with propellants and with a crew on the spacecraft.

Immediately after the scrub, ULA CEO Tory Bruno left open the option of trying again as soon as the next night. “We could be ready tomorrow if we find out we have plenty of life” in the valve, he said at a briefing a couple hours after the scrub. However, ULA ultimately decided to replace the valve, which involved rolling the rocket back to its hangar.

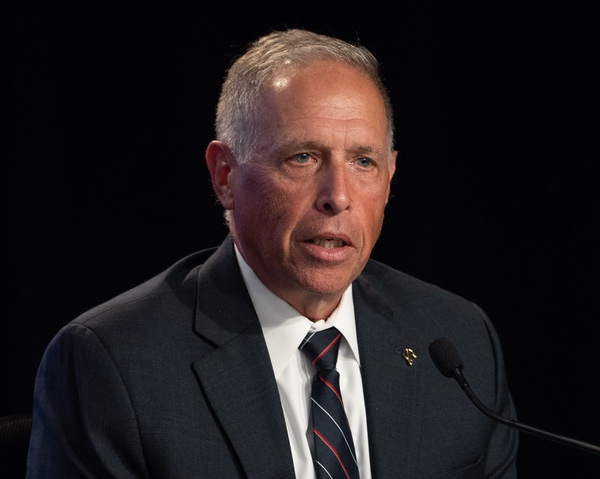

Boeing vice president and commercial crew program manager Mark Nappi after the May 6 scrub. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky) |

In that process, though, Boeing found a helium leak with a thruster on Starliner’s service module. That led to a schedule dance of sorts lasting a couple weeks: NASA would announce it was pushing back the launch several days to further study the leak, only to announce a few days later another delay, without providing details on what was going on with the leak or anything else that might be causing the delay.

| “This is really not a safety-of-flight issue for ourselves, and we believe that we have a well-understood condition that we can manage,” Nappi said of the helium leak. |

Finally, on May 24—the Friday before Memorial Day weekend—NASA held a briefing on what was holding up Starliner, now that the faulty Centaur valve was replaced. “We are learning more about the system every day,” Jim Free, NASA associate administrator, said at the start of the briefing, describing how NASA and Boeing sought the “right balance” of updates what that was ongoing.

The 90-minute briefing started with the helium leak. Engineers concluded the leak was a flaw in a single seal: a rubber ring the diameter of a shirt button and the thickness of ten sheets of paper. A defect in the seal caused the leak, first noticed immediately after the May 6 scrub, to grow worse as it was tested.

Boeing and NASA concluded that Starliner could fly as-is: the leak was not a major risk, and replacing the seal would have required extensive repair work. “If we were to remove the seal completely,” Nappi said, “the leak rate would not exceed our capability to manage that leak. That made us comfortable that, if this leak were to get worse, it would be acceptable to fly.”

Other work conclude that the damaged seal was not a systemic problem, with no evidence of problems with any other seals in the spacecraft’s propulsion system. “This is really not a safety-of-flight issue for ourselves, and we believe that we have a well-understood condition that we can manage,” Nappi concluded.

So far, so good. NASA’s Stich said at the briefing that engineers used this time to perform other reviews of the propulsion system, a step he said was intended to “make sure we didn’t have any other things that we should be concerned about.”

As it turned out, there was something to be concerned about. The review turned up what he called a “design vulnerability” with Starliner’s propulsion system that had not been recognized. Starliner’s service module has four areas called “doghouses” spaced 90 degrees apart that host both larger Orbital Maneuvering and Attitude Control (OMAC) thrusters and smaller reaction control system (RCS) thrusters. If two adjacent doghouses failed for some reason, though, it would prevent the spacecraft from doing a deorbit burn even though the spacecraft is designed with multiple ways to carry out the deorbit burn using combinations of OMAC and RCS thrusters.

“It’s a pretty diabolical case,” Stich said of that scenario, which he and Nappi emphasized was rare, occurring in less than one percent of the potential combinations of failures in the propulsion system. “You would lose two helium manifolds in two separate doghouses, and they have to be next to each other.”

NASA and Boeing developed another approach to doing the deorbit burn using four RCS thrusters, splitting the deorbit maneuver into two separate burns. But the late discovery of this design vulnerability prompted questions about why it was found only now, after years of development and scrutiny—particularly since it came two months after the agency and the company made the case their reviews had not missed anything.

“The helium leak itself caused us to look a little more in detail in the manifolds and how the thrusters were architected off of each of those manifolds,” Stich said, which revealed the vulnerability. “It just took us a little time to figure this out now. The question is, should we have seen this earlier? Maybe in a perfect timeframe we might have identified this earlier.”

With the helium leak no longer a concern and the design vulnerability identified and temporarily corrected—Nappi said Boeing was looking at several permanent fixes to the problem, using some combination of hardware changes and software modifications, for later Starliner missions—it was time to try to launch Starliner again, this time on June 1.

Astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore greet well-wishers before boarding a van to the launch pad for the June 1 launch attempt. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky) |

The countdown was going well other than an issue about two hours before liftoff with the Centaur, this time with valves used for replenishing or “topping” the vehicle with liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. The problem was initially linked to malfunctioning sensors, which controllers corrected by switching to another set, allowing the valves to resume operations. Launch preparations continued into the final minutes.

Then, seconds after the rocket exited its pre-planned T-4 minute hold, a call of “Hold! Hold! Hold!” was heard. A rocket issue of some kind halted the countdown and, with an instantaneous launch window, scrubbed that day’s launch attempt.

| “It’s human to be a little disappointed,” Stich said. “Everyone’s a little disappointed, but you roll your sleeves up and get back to work.” |

The problem, ULA’s Bruno said at a later briefing, was with one of three redundant ground control computers, housed in racks that hold cards responsible for various tasks. A card known as the launch sequencer came up slower in one computer than in the other two, a discrepancy that “tripped a red line” and caused the hold, he said.

Another card in the same computer was responsible for the topping valve issue seen earlier in the countdown, he said. Those cards have been reliable, he said, although “it’s not unheard of to replace a card.” They were tested in the preparations leading up to the launch and were working well, he said.

At the time of the briefing, Bruno said it might be possible to replace a faulty card or cards in time for a launch attempt the next day, but a couple hours later NASA said they would skip that launch opportunity to provide ULA with more time to resolve the problem. NASA said late June 2 that ULA found a problem with a power supply for part of that computer rack. ULA replaced and retested that rack, allowing a launch attempt June 5, the next available opportunity.

Ironically, for all its problems in the past, Starliner was in good shape during the launch attempt, with only a brief issue with power to fans that circulate air in the pressure suits worn by the astronauts. The helium leak not only hadn’t gotten worse but instead had actually decreased.

Officials acknowledged the delays were frustrating but that they and others working on Starliner remained focused. “It’s human to be a little disappointed,” Stich said. “Everyone’s a little disappointed, but you roll your sleeves up and get back to work.”

“When you’re playing a game and you get a bad call, you’re a little irritated at first, a little frustrated at first,” Nappi said, “but you need to focus on the next pitch.”

That next pitch is scheduled to come Wednesday, with NASA confirming late Monday that the launch remained on track and that weather remained favorable (remarkably weather has not been an issue for the previous Starliner launch attempts in recent weeks.) There is another opportunity Thursday but, after that, ULA said it may need to replace batteries on the Atlas 5, work that would take about 10 days, pushing the next launch to the second half of June.

NASA says it remains committed to Starliner, seeking “dissimilar redundancy” that two different vehicles launched on two different rockets provide for accessing the ISS. NASA had hoped to start flying astronauts to the station on Starliner early next year, a mission designated Starliner-1, alternating missions with SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, but it’s not clear now if the certification work can be completed in time to support that schedule.

“That will be something that we will work on after the flight,” Stich said of certification before the June 1 launch. “The path to Starliner-1 clearly is through Crew Flight Test. That is the most important thing we have towards certification.”

“The longer it takes to fly CFT, the shorter that period becomes for us to review that data” from the flight, Nappi said. “Getting the certification review done as soon as we can is important regardless of when we fly.”

What is perhaps most remarkable about the situation is how much things have changed in the last decade. Boeing seemed the obvious choice at the time for one commercial crew award, and may well have been the leading candidate if NASA decided to make only one. The company, after all, had decades of experience in human spaceflight. Moreover, it was working with ULA, which at the time handled nearly all major US government launches. What could possibly go wrong?

Today, Starliner is now at least four years behind SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, which launched on its successful crewed test flight in May 2020. The Starliner launch is set to be ULA’s third launch of 2024, after the debut of Vulcan and retirement of the Delta IV Heavy; SpaceX launched 14 Falcon 9 rockets in May alone.

A successful test flight launching this week won’t fix all those problems, but could at least get the program moving in the right direction so it doesn’t lose any more ground.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.