Space isn’t all about the “race”: rival superpowers must work together for a better futureby Art Cotterell

|

| But what is this latest “race” about, and are there pathways to common ground? History suggests these do exist. |

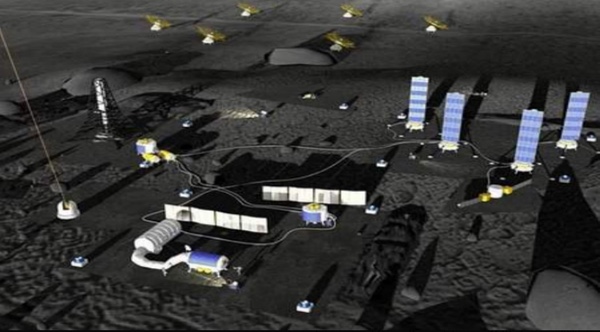

Geopolitical tensions are again moving off-Earth. The US and China are leading separate missions which aim to return humans to the Moon. One goal is to further scientific research. But space mining and economic expansionism are also driving these efforts.

This new “race” may give rise to new conflicts, especially over prime landing sites and valuable and scarce resources speculated to be located on the lunar south pole.

Mining water ice could produce oxygen, drinking water and rocket fuel, all vital for sustaining lunar exploration and beyond. The Moon may also contain rare earth metals used in everyday electronics, and a rare non-radioactive isotope, helium-3, for nuclear power.

Space mining could lead to a concerning “lunar gold rush” or trade war with nations and private actors in space. Resources mined off-Earth are predicted to be worth trillions of dollars.

The US has a longer history of demonstrated spacefaring capabilities, investments, and partnerships. Yet China is catching up. While the US made its first uncrewed landing on the lunar south pole this year, China has made several landings. In June this year, China’s Chang’e 6 mission returned with the first rock and soil samples from this sought-after region of the Moon.

How are nations working together on space?

Both superpowers have invited other nations to join them in realizing their lunar visions. Last week the Dominican Republic became the 44th signatory to the US-led Artemis Accords.

Thirteen other nations are participating in the China-led International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) in collaboration with Russia. Senegal joined last month.

With no membership overlap between the two initiatives, new “space blocs” are emerging, reflective of global power dynamics.

| We’re at a critical juncture. It’s important the emergence of these new “space blocs” doesn’t escalate into a contest over whose space governance approach prevails. |

The Artemis Accords and ILRS are currently not legally binding, but they will be influential in shaping space governance in the 21st century. This is because treaty-making in the United Nations’ Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS, established in 1959) hasn’t kept pace with the latest developments and actors in space. Nor has space governance adequately engaged with growing ethical questions, including on space colonization and light pollution caused by satellites.

We’re at a critical juncture. It’s important the emergence of these new “space blocs” doesn’t escalate into a contest over whose space governance approach prevails. Not only could this increase the risk of conflict on the lunar surface itself, but it could even fuel geopolitical instability and military competition on Earth.

History shows we can work together

Space has fostered cooperation even between superpower rivals during tense geopolitical times. During the Cold War, the US and Soviet Union cooperated on space governance, laws, science and technologies. This built mutual trust and eased tensions.

Within COPUOS, nations worked together to agree on what became the first of multiple foundational space law treaties, the Outer Space Treaty in 1967. It prohibits placing nuclear weapons in space and national appropriation claims over celestial bodies like the Moon.

A joint Moon landing never took place. But in 1975, Apollo and Soyuz spacecraft docked while in orbit. This marked the first international human spaceflight partnership, a historic feat made possible thanks to technical cooperation and diplomacy. COPUOS heralded this as inspiring ongoing cooperation.

More recently, NASA’s International Space Station (ISS) has been an orbiting testament to coexistence. Astronauts from the US, Russia, and other partners have conducted over 3,000 experiments in microgravity.

At the recent UN Summit of the Future, video messages from the ISS and China’s Tiangong space station astronauts reaffirmed the importance of international cooperation and the peaceful uses of space.

From rhetoric to practice

Humanity has much to lose if global superpowers don’t cooperate on space governance. There is a real and growing risk of exporting and exacerbating our earthly conflicts in space. This will invariably increase tensions on Earth.

The US and China need to explore opportunities to open dialogue between the Artemis Accords and ILRS. There are some similarities in their separate planned activities, governing principles, and guidelines already.

To make this happen, the US will need to revisit the 2011 Wolf Amendment, a law that restricts NASA from using its funding to cooperate with China without congressional approval. But China has no equivalent and recently expressed its willingness to cooperate, including sharing its rock and soil samples.

Sharing scientific information may help find initial common ground before further discussions on space governance. This could even move towards agreeing on landing sites or a lunar time zone. If a rescue mission is ever necessary on the Moon, having some compatible technology through interoperability would make it much easier.

The US and China do actively engage in COPUOS, including in the working group on space resources. Yet treaty-making is often slow moving. This means greater opportunities for communication, consistency and certainty on space governance are imperative. This could even support multilateral efforts.

Perhaps a joint lunar research mission between the US and China—in the spirit of the Apollo-Soyuz docking—can still happen in the future.

In the meantime, the world needs to see space not only in terms of a “race”. It’s also an opportunity to improve international relations, benefiting our future humanity on Earth and, one day, beyond.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.