The trials and tribulations of Heraby Jeff Foust

|

| “It worked out. A little bit of magic today. For once we were lucky,” Carnelli said after liftoff. |

ESA has turned to SpaceX to launch Hera on a Falcon 9 given delays with the development of its Ariane 6, just as it did for its Euclid and EarthCARE missions. The Falcon 9 has been a remarkably successful launch vehicle, but a little more than a week before the scheduled launch, a Falcon 9 upper stage suffered what SpaceX called “an off-nominal deorbit burn” at the end of the Crew-9 mission, causing the upper stage to deorbit outside of its designated zone in the South Pacific east of New Zealand.

In the days leading up to the scheduled October 7 launch, project officials said they were continuing launch preparations so they would be ready when the rocket was. “We are maintaining the nominal launch campaign,” Ian Carnelli, ESA project manager for Hera, said at an October 2 briefing. The window, he noted, ran through October 27.

The day before the launch, he brought good news to a briefing at a Cocoa Beach, Florida, hotel: SpaceX had gotten approval to launch Hera. A short time later, the FAA said it allowed the launch to proceed since there would be no deorbit burn on this mission—the upper stage and Hera would go into Earth-escape trajectories—and thus no public safety concerns.

“The last hurdle is the weather,” he concluded. The day before the launch, forecasters projected just a 15% chance of acceptable weather for the October 7 launch attempt, which had an instantaneous launch window, and only slight better the next day. After that, though, all eyes were on the rapidly strengthening Hurricane Milton, barreling towards Florida on a path that would take it directly over Cape Canaveral. That would further delay the launch, further complicated by NASA’s Europa Clipper, slated to launch October 10 from KSC. In a worst-case scenario, that would push Hera’s launch relatively deep into its three-week launch period.

But a 15% chance of acceptable weather is better than 0%. And, on that Monday morning, conditions remarkably remained favorable. SpaceX pressed ahead with a launch attempt, knowing this might be the only chance for a week or more. And, at 10:52 am, the Falcon 9 lifted off, beating the weather odds and hurling Hera into the solar system.

“Man, that was a heart attack,” Carnelli said of the weather in an interview a few hours after the launch. A line of showers was approaching, he said, but forecasters determined they would not arrive until after the scheduled liftoff. “It worked out. A little bit of magic today. For once we were lucky.”

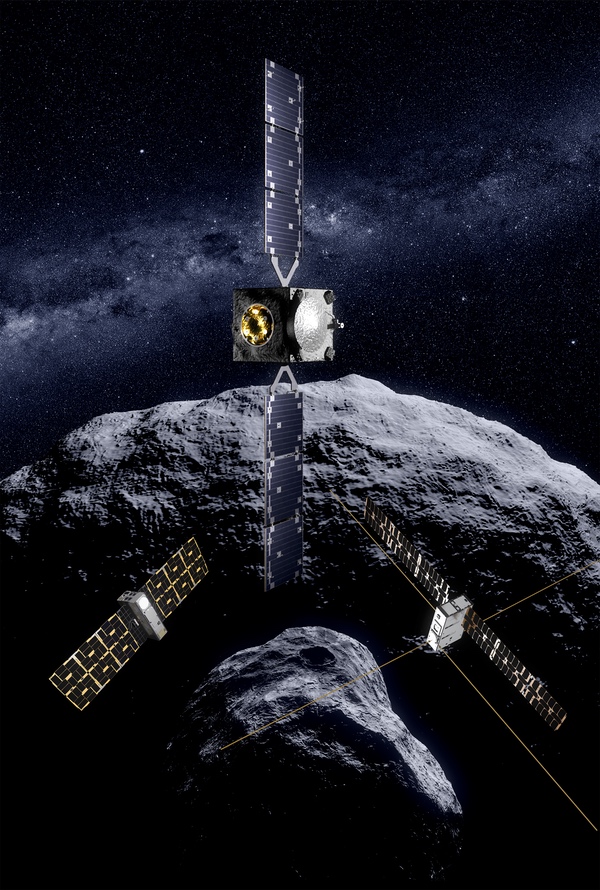

An illustration of Hera and its two cubesats, Juventas and Milani. (credit: ESA) |

From Don Quijote to Hera

Hera is a mission to the near Earth asteroid Didymos and its moon, Dimorphos, arriving in late 2026. It was Dimorphos that NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft deliberately collided with two years ago as a demonstration of the kinetic impactor technique for changing the orbit of a potentially hazardous asteroid. DART changed the orbital period of Dimorphos by a half-hour, exceeding expectations.

Hera will follow up on DART to study the asteroids in detail. “With Hera, it’s like a detective going back to a crime scene,” said Patrick Michel, principal investigator for the mission, at a prelaunch briefing.

“The first thing is to find out how efficient the impact was,” said Michael Kueppers, Hera project scientist, at another briefing. Measuring the mass of Dimorphos will help scientists understand how much of a push it received from the spacecraft impact itself and how much came from ejecta thrown off the asteroid by the impact, providing an additional push.

| “With Hera, it’s like a detective going back to a crime scene,” said Michel. |

Other instruments will image the asteroids, with a particular interest in whether DART left an impact crater or instead reshaped Dimorphos, thought to be a loosely bound “rubble pile” asteroid. “We will learn a whole lot about how the impact process works,” he said. “Apart from the scientific interest, this is highly valuable if we want to apply the technique in a real case.”

In addition to its 12 instruments, Hera is flying two cubesats. Juventas has a radar designed to map the interior of Dimorphos, while Milani will study the surfaces of the two asteroids and their composition. Both will end their missions by trying to land on Hera; Juventas has a gravimeter that will be used to measure the asteroid’s gravitational field during that landing attempt.

“We don’t really know what we will see,” Michel said, noting there are many models of what the DART impact did to Dimorphos. “We’re going to have a surprise when we see what Dimorphos looks like, which is, first, scientifically exciting but also important because if we want to validate the technique and validate the model that can reproduce the impact, we need to go find out the outcome.”

Hera is a mission that had an unusually long gestation period, followed by a rapid development phase. It traces its roots to a mission concept called Don Quijote—led by the late Italian planetary scientist Andrea Milani, after whom Hera’s Milani cubesat is named—two decades ago as part of an ESA effort to study potential planetary defense missions. That original concept featured two spacecraft: one would impact an asteroid and the other with monitor the collision and its effects.

ESA selected Don Quijote for further study, but the mission could not win financial support. ESA then partnered with NASA on what they called the Asteroid Impact and Deflection Assessment (AIDA) mission, with NASA launching DART and ESA flying the Asteroid Impact Mission (AIM) to observe the DART impact. But AIM failed to win sufficient funding at an ESA ministerial meeting in 2016, and it appeared that DART would go it alone.

ESA regrouped, proposing a less expensive mission called Hera that would do the followup observations after the impact. That won funding at the next ESA ministerial meeting in late 2019, allowing mission development to go forward just months before the pandemic hit.

“Nobody believed we were going to make it,” Carnelli recalled, as the project figured out how to maintain progress and deal with supply chain impacts caused by the pandemic. “The fact that we had a very strict launch window, I think, pushed every single supplier to do their best.”

It was, though, not without problems. “We had components that came in with human hair inside, and we had to return them,” he recalled after the launch. In another case, the project received a $100,000 processor and was in the process of installing it “when we realized it was marked ‘For Exhibition Only.’ It was empty.”

Hera, though, also demonstrated the ability of ESA and industry to move quickly on a spacecraft mission and take unconventional approaches. He noted that the final flight software was compiled on the flight from Europe to Florida, and sent in-flight via WhatsApp to the ground team at the Cape working on final mission preparations. It was tested and installed within hours. “I don’t think this has ever been done before.”

| “I hope Hera is going to pave the way for many more missions that are fast and innovative,” Carnelli said. |

Moreover, the €363 million ($395 million) mission came in under budget. That freed up €20 million in funding to start studies of another asteroid mission, Ramses, that is designed to rendezvous with the asteroid Apophis shortly before it makes a very close approach to the Earth in 2029. Ramses, as currently envisioned, would use a stripped-down version of the Hera spacecraft with a single-string architecture, like NASA’s DART.

“I think we will gain a tailwind for Ramses,” said Walther Pelzer, director general of the German Space Agency at DLR, in a prelaunch interview. Germany was the largest single contributor to Hera, driven by both interest in planetary defense as well as technology development for the mission itself.

He added there was strong public interest in Hera in Germany. When DLR posted an interview about the mission on its website, he recalled, “there was a very, very high response, higher than even Ariane 6.”

“I hope Hera is going to pave the way for many more missions that are fast and innovative,” Carnelli said before liftoff. “It involves risk-taking, for sure, but we’re exploring the solar system in new ways.”

After the launch, he was simply happy that Hera was on its way to Didymos and Dimorphos, with all spacecraft systems working well. “I guess this is the story of every space mission, right?” he said of the challenges the project faced getting Hera launched. “It was a ride.”

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.