Mysterious MOL conceptsLong forgotten manned military space station ambitionsby Hans Dolfing

|

| What is under appreciated is the amount of spaceflight vision, ambition, and concept studies in that time. |

Within that historical context, December 1963 recorded two important events related to manned spaceflight and the following fiscal year's budget. The military Dyna-Soar (X-20) space glider was cancelled and the USAF ambitions for space were reduced to a small military space station called the Manned Orbital Laboratory (MOL), which was announced December 10, 1963.

What is under appreciated is the amount of spaceflight vision, ambition, and concept studies in that time. This article highlights a few forgotten MOL concepts discussed behind the scenes based on documents preserved at the National Archives and Records (NARA) that demonstrate those grand USAF ambitions that were ultimately curtailed into the small MOL announced in December 1963. [1,2]

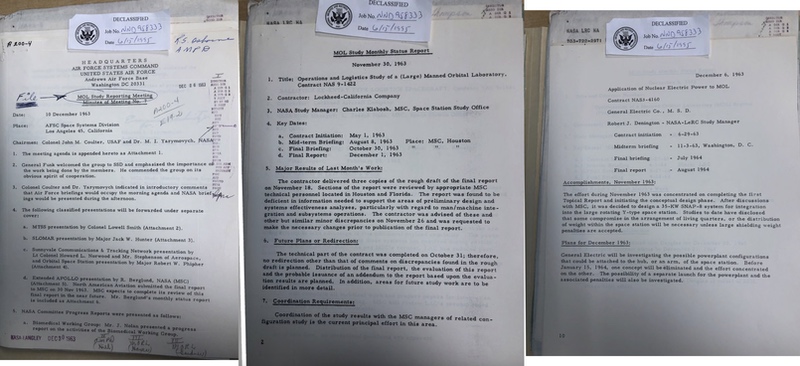

First, as part of a set of almost 40 pages, NARA has documents from HQ Air Force System Command (AFSC) titled “MOL Study Reporting Meeting Minutes of Meeting No. 7” dated December 10, 1963.[1] The meeting took place at AFSC Space Systems Division (SSD) in Los Angeles and the chairmen were Col. John M. Coulter and Dr. M. I. Yarymovych from NASA. The two-page cover letter and one-page agenda show that several presentations on the SR-17527 Military Test Space Station (MTSS), SR-79814 Space Logistics, Maintenance and Rescue (SLOMAR) and Extended Apollo were contributed to this MOL meeting. Figure 2 shows three example pages. NASA contributed reports from its biomedical and scientific experiment workgroups. [1]

Figure 2: Example documents [1] |

The two-page distribution list shows that these meeting minutes were copied to a list of illustrious spaceflight names including Wernher von Braun (NASA Marshall Space Flight Center), Abe Silverstein (NASA Lewis Research Center), George von Tiesenhausen (NASA Launch Operations Center), Rene Berglund and Edward Olling (NASA Manned Spacecraft Center), Col. Lowell Smith (USAF MTSS liaison) and dozens more.

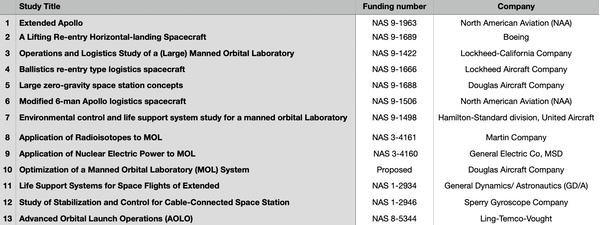

To further demonstrate the scope of spaceflight related studies flowing into these MOL meetings, here is the list of studies attached to this particular seventh MOL meeting, which include many "MOL Study Monthly Status Report" with reports on various activities and subcontracts. These one-page status documents include details and schedules. Table 1 summarizes the status reports.

Table 1: List of "MOL Study Monthly Status Report" at 7th meeting Dec. 10, 1963. [1] |

Related to these meeting minutes, there is an undated, five-page work statement titled “A study of the Operational Problems Associated with A Manned Orbiting Telescope,” plus a one-page cover letter and two-page justification. This was clearly written by Langley Research Center (LaRC) in 1963 as part of a small concept study.

| To summarize these archival documents, almost 40 pages discuss mostly forgotten projects feeding into the MOL space station concept before its announcement in December 1963. |

Finally, there is a three-page memo on "Eighth Manned Orbital Laboratory Study Reporting Meeting" dated January 5, 1964. On the military USAF side, the document says that the USAF still wishes to go ahead with its OSS Study as originally planned, though it is unapproved at that date. Also, the published MOL configuration is not necessarily the final configuration though it is clear it will not have a centrifuge. On the civilian NASA side, NASA’s position towards the MOL program has been clarified and the NASA space station activities have been grouped under an umbrella program called Orbital Research Laboratory (ORL) comprising four programs with increasingly longer stays in space named Apollo-X, Apollo Research Laboratory (AORL), MORL where the M stand for Manned or Medium, and LORL as the largest facility.

To summarize these archival documents, almost 40 pages discuss mostly forgotten projects feeding into the MOL space station concept before its announcement in December 1963 with a few example pages in Figure 2. [1] Below are more details on the telescope proposal, the nuclear power source, and the thinking about a very large space station for the USAF.

The discussion about telescopes in space was ongoing in the US already in the 1950s when Wernher von Braun discussed the concept for astronomical purpose. Similarly, Nancy Roman already wrote in 1960 about the advantages of telescopes in space, which is one reason why NASA has named a future space-based telescope after her.[4,14]

The role of the MOL was primarily aimed at finding out the military requirements in space. In Figure 1, a small telescope was attached to the MOL for Earth observations. The larger types of space stations, to be discussed later, had much greater potential for astronomical and other observations.

As telescopes can look up and down, the military realized that a small telescope in orbit or a larger one of the Moon could be useful for observations of Earth. In California, the astronomical Hale telescope on Mt. Palomar with a 200-inch (five-meter) mirror was completed in 1949. Based on that experience, it is known that military, space-based 200-inch manned telescopes were considered in 1959. One option was to be based on the Moon to achieve 100-foot (30-meter) resolution in Earth imaging.[15] Obviously that was not good enough compared to the one-foot (30-centimeter) resolution requested during the MOL program in 1965, which is why discussion on space locations and orbits, ground resolution, and budgets were ongoing.[3]

The NARA documents discuss an early Langley Research Center study on a 120-inch (four-meter) Manned Orbital Telescope for astronomical purposes. The manned aspect is emphasized as advantageous for operation and maintenance.

For comparison, the concept of a 120-inch Manned Orbital Telescope for astronomical purpose in a 200-nautical-mile (370-kilometer) orbit in 1963 is indeed a sizable mirror. Actually, it is a large mirror compared to Hubble (96-iinch), the ground-based Mt. Palomar (200-inch) and later MOL studies labelled Dorian and KH-10 (72-inch).

The NARA document also mentions that the optical aspects would be studied more by a company named “Fecker” leading to a final report that concentrates on the technical aspects and barely mentions manned operation at all.[12] That report seems to indicate that manned telescope operation was unnecessary but a large telescope in space was technically feasible.

In summary, the manned orbital telescope was a topic of discussion in 1963, as part of the wider discussion what man’s role in space was going to be for both civilian and military projects. The enabling effects of what is now known as exponential growth of computing power was only starting to register.

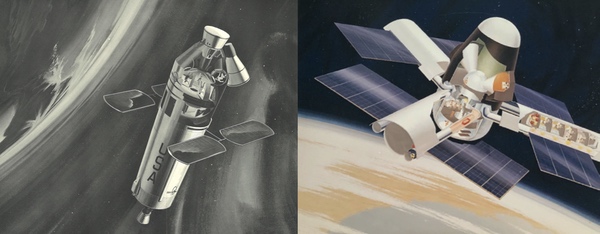

Figure 3: Lockheed “Tinkertoy” concept [2,16,17] |

To continue from telescopes to larger space stations, at the time of the announcement in December 1963, the MOL was going to be a small military space station for one or two astronauts, zero-G environment, with a pressurized volume of about 1,000 to 1,500 cubic feet (28–42 cubic meters).[3] That size was very similar to some space station sizes in the phase I of the even earlier MTSS concepts.[13]

| In the middle of 1963 the military mission in space was not well defined. A small station was needed to define the military missions better. |

On the civilian side, NASA was very clear that a large space station would not be achieved in a single step due to too many unknown factors.[2] That explains why small, medium, and large space stations were studied at the same time as MOL because this would provide better knowledge on how to scale up in future. One particular unanswered question was how effective can men work in space, with the related question whether zero-G stations were simply good enough or whether spin-gravity was required for effective work in space. Keep in mind that Apollo was the main human space effort in the country and budgets for military space were shrinking as a result.

In particular, NASA investigated a medium-sized Manned Orbital Research Laboratory (MORL) that also had a larger cousin, the Large Orbital Research Laboratory (LORL), with a projected volume of 67,000 cubic feet (1,900 cubic meters) and 24 astronauts or more.[2,5,10,11]

In June 1963, after several years of internal studies, Douglas Aircraft got a two-phase civilian contract for MORL as well as a LORL zero-G contract in August 1963.[10] In parallel, LMSC studied a large station with artificial gravity and had looked at a large “Tinkertoy” station a few years earlier.[2,11] The NARA documents show all of this was still on the table on the military side before a much smaller military station was announced in December 1963.

Additional contemporary work on space stations is supported by the earlier Table 1, entry 1, by North American Aviation. The monthly status report says, “The Phase I contract (NAS 9-1963) of the Extended Apollo terminated as of Nov. 30, 1963 with the submission of the final report except for Addendum No. 1 which is for the total price of $49,000 to investigate ‘Modular Concepts.’ Work under the addendum began Nov. 18, 1963.”[1]

For more work on the large space station, we find in entry 5 in Table 1, which also mentions the study “Large Zero-Gravity Space Station Concepts” by Douglas Aircraft. It says, “‘Preliminary design’ effort is continuing in a satisfactory manner. Work is divided into two separate efforts at this time. Subsystems are being integrated using the Phase I trade-off studies and the external and internal structural configurations are being determined. The preliminary system design specification is continuously being revised as the system design is formulated.” This work is related to the left concept in Figure 4.[1,10]

Figure 4: Douglas and Lockheed LORL concepts |

Finally, as entry 3 in Table 1, and also Figure 2, there is Lockheed working on a contract titled “Operations and Logistics Study of a (Large) Manned Orbital Laboratory,” which relates to both Figure 3 and 4. The status mentions “The contractor delivered three copies of the rough draft of the final report on November 18,” which demonstrates there was hard work going on to feed preliminary work on large orbital stations to the military space station meetings before the decision was made for a small MOL station. The Lockheed logistics study NAS 9-1422 was overlapping with the large rotating station in NAS9-1655, which contains the concept on the right in Figure 4.[1,11]

To summarize, there were several reasons to go from a “big” to a “small” MOL. First, in the middle of 1963 the military mission in space was not well defined. A small station was needed to define the military missions better. In addition, contracting budgets and sanity prevailed to start with a small military station to answer specific military questions though even a few months earlier far larger military stations were considered for MOL. Had it not been for the war in Vietnam, and a Cold War race to moon via Apollo, the budgets might have supported very different goals such as both large civilian and military space stations.

Finally, on nuclear energy, in the 1950s and 1960s, nuclear energy was seen as the way of the future. Application anywhere including in space was a natural thing to study.[6,9] Within that context, the Systems Nuclear Auxiliary POWER (SNAP) program studied both radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTG) as well as space nuclear reactors.[7,8,18] The difference was typically in the way heat was transformed to power. The RTG projects were typically odd numbered while the even-numbered studies were nuclear reactors. [7]

Nuclear power for the MOL was studied both ways. Per Table 1, entry 8, a Martin Company study investigated to use radioisotopes to generate power, specifically via polonium-210 and a Brayton cycle. It was titled “Application of Radioisotopes to MOL” and carried out between June 1963 and February 1964, reported on December 6, 1963.

| Sadly, the “von Braun” ideas of large space stations would not be pursued for decades by either the civilian or military agencies. |

The transport of such radioactive cargo to a space station presented unique challenges. One proposed approach was to mount the RTG and materials on the outside of the Mercury capsule, which would improve the shielding for the astronauts. The complication would be that this would be an imbalance of the capsule and would require more counterweights to keep it stable.

Another nuclear energy study considered was a SNAP-8 reactor with 35 kilowatts output to power MOL. Per the NARA documents in Figure 2 as well as Table 1, entry 9, the study was titled “Application of Nuclear Electric Power to MOL,” between June 1963 and August 1964, by General Electric Co., MSD and status reported on December 6, 1963.[6]

The status report says:

Accomplishments, November 1963:

The effort during November 1963 was concentrated on completing the first Topical Report and initiating the conceptual design phase. After discussions with MSC, it was decided to design a 35-KW SNAP-8 system for integration into the large rotating Y-type space station. Studies to date have disclosed that some compromise in the arrangement of living quarters, or the distribution of weight within the space station will be necessary unless large shielding weight penalties are accepted.

Plans for December 1963:

General Electric will be investigating the possible powerplant configurations that could be attached to the hub, or an arm, of the space station. Before January 15, 1964, one concept will be eliminated and the effort concentrated on the other. The possibility of a separate launch for the powerplant and the associated penalties will also be investigated.

As with RTGs, shielding of the reactor was important. A full shield around the reactor would be prohibitively heavy and impossible to launch. Therefore, the practical approach was to mount the reactor away from the astronauts on an extended beam or similar. An alternative approach involved a “shadow shield” between reactor and astronauts. SNAP-8 had a joint AEC- and NASA-sponsored development and was envisioned with a 30- to 60-kilowatt output for about 1.5 years.[7] SNAP-8 was tested on December 11, 1963, to full power for the first time, which is one day after the seventh MOL meeting discussed earlier.[18] We can only speculate on the dates but it almost looks like there was an effort to achieve this datapoint in time for this meeting.

While odd-numbered RTGs made it to space, e.g., in the Transit satellites, the SNAP-8 reactor envisioned for MOL never reached space.[9,18]

To summarize, these NARA documents showed that the USAF vision in 1963 included very large orbital stations powered by nuclear reactors, which then required a large logistics effort with shuttles to support the military mission in space. Shrinking budgets and an unclear military mission in space collapsed those visions into a small, single launch orbital station called the MOL.

Sadly, the “von Braun” ideas of large space stations would not be pursued for decades by either the civilian or military agencies. Instead, the nation concentrated on the singular, peaceful goal of Apollo to land a man on the Moon while the military was put on a reconnaissance track in space.

References

- RG 255, NACA Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory and NASA Langley Research Center Records, A200-4 Manned Space Stations, Series II: Subject Correspondence Files, 1918-1978, Box 421, Sep. 1963 - Nov. 1964, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Philadelphia.

- Irving Stambler, “Orbiting Stations; Stopovers to Space Travel”, LCCN 65020700, published by G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1965.

- “The DORIAN files revealed : A compendium of the NRO's Manned Orbiting Laboratory documents”, edited by James D. Outzen, Ph.D., incl. Carl Berger’s - “A History of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory Program Office” Aug. 2015

- Wernher von Braun, “Collier’s articles on conquest of space (1952-1954)”

- Roger D. Launius, Space Stations: Base camps to the stars, ISBN 1-56852-716-0, 276 pages, 2003

- “Nuclear electric power for manned orbiting space station Final presentation”, NTRS 19690071195, CR-105379, 69N75374, NAS3-4160

- “SNAP-8 Summary report”, Atomics International Division, Rockwell International, AI-AEC-13070, 1973

- Wikipedia, “Systems for Nuclear Auxiliary Power (SNAP)”

- Dwayne A. Day, “Nuclear Transit: nuclear-powered navigation satellites in the early 1960s”, "The Space Review", February 2024.

- “Douglas Orbital Laboratory Studies”, Douglas Report SM-45878, January 1964, Missile & Space Systems Division (MSSD), Santa Monica, CA via JSC History Collection at University of Houston-Clear Lake, Space Station Series,McDonnell Douglas, Box Number 2.

- “Study of a Rotating Manned Orbital Space Station”, Lockheed Spacecraft Organization, California, Burbank, submitted to NASA Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), Houston, Texas, March 1964, NAS9-1665, LR-17502, cost $300,000, NTRS 19640047936,19640047964 et al, 11 volumes via Bellcomm, Inc Technical Library Collection, Accession XXXX-0093, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution., Box 139, Folder 11 to Box 141, Folder 7.

- “Final Report Feasibility Study of a 120-inch Orbiting Astronomical Telescope”, AE-1148, NTRS 19720068070, NAS1-1305 by J.W. Fecker Division, American Optical Company, Pittsburgh, PA./li>

- H. Dolfing, “The Military Test Space Station (MTSS)“, "The Space Review", August 2024.

- Nancy G. Roman, “Satellite Astronomical Observations" in "Proceedings of the Manned Space Station Symposium”, pp 125-127, Los Angeles, CA, April 20-22 1960.

- ”S.R. 183 Lunar Observatory Study”, Project No. 7987, Task No. 19769, Volume 1 and 2, AFBMD TR 60-44, April 1960.

- “Tinkertoy, early Lockheed space station concept by Saunders B. Kramer”, NASA History Division, RG-11, Boxes 9088 and 9090.

- Saunders B. Kramer, “Early engineering designs of space stations in the United States: A Memoir”, Journal of the British Interplanetary Society (JBIS), Vol. 46, pp. 163-172, 1993.

- “US Astro-nuclear History part 2: SNAP-8, NASA’s Space Station Power Supply”, BeyondNerva, 2018.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.