Vandenberg and the space shuttle (part 1)by Dwayne A. Day

|

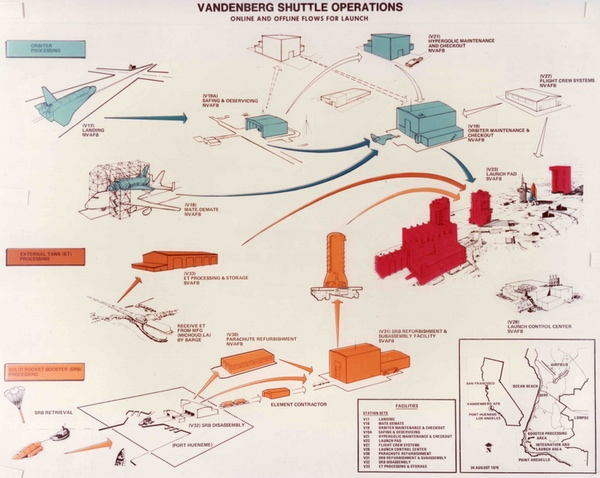

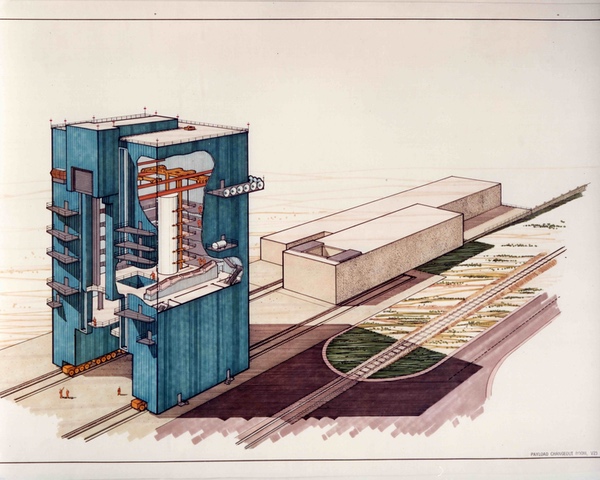

To support the shuttle, Vandenberg Air Force Base required major construction of multiple new support facilities. Many of these were on the main base, with the launch complex on the south base. This artwork was created in the late 1970s to illustrate the required construction. (credit: USAF) |

Recently, this author discovered a collection of Vandenberg shuttle facility concept art during the construction proposal stage in the late 1970s. The art was used in briefings to illustrate what the many large buildings would look like and how they would support the space shuttle program. Although some of these illustrations have been published in shuttle histories before, most have never been public. The buildings were constructed but never used for the space shuttle, some remaining vacant for decades. What the collection illustrates is the scope of the effort required to support West Coast shuttle launches, not just a mostly new launch pad complex, but many additional structures to service a complex new space vehicle.

For California launches, the shuttle had to be able to land at Vandenberg, requiring lengthening the base's runway. (credit: USAF) |

Bringing shuttle to the West Coast

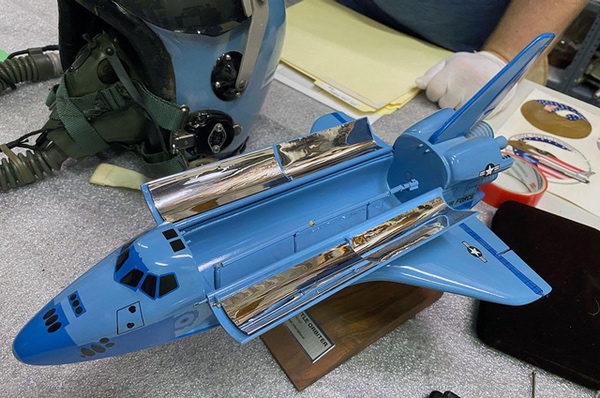

When President Richard Nixon approved the space shuttle program in 1972, he also agreed to a policy change that would require all US government as well as commercial payloads to switch from expendable launch vehicles to the semi-reusable space shuttle. This was a controversial decision, especially within the Pentagon, which was reluctant to use a launch vehicle that the military did not directly own and control. Shifting military payloads to the space shuttle meant that the government would have to build a West Coast shuttle launch site to support polar and high-inclination launches. Because most of these were military payloads, the Air Force was responsible for building and paying for the Vandenberg shuttle facilities. Some defense contractors even made shuttle models painted Air Force blue to celebrate the Air Force involvement in the program.

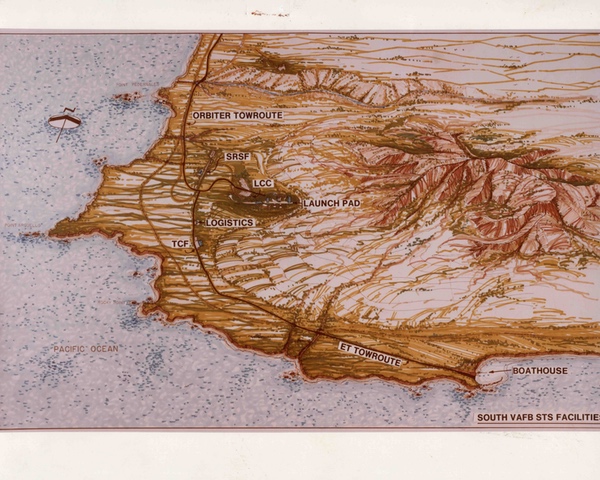

The southern end of Vandenberg, where the launch complex was located, has the Pacific Ocean on one side and low mountains on the other. Shuttle components had to be brought in from both the north and south. (credit: USAF) |

When NASA officials began planning for the shuttle in the early 1970s, they predicted 40 shuttles would launch from Florida and 20 from California each year. By 1977, this was revised down to approximately 17 annual launches from California—a mix of reconnaissance and weather satellites. The number was soon further revised down to approximately 13 per year. At that time, the Air Force envisioned up to two pads at Vandenberg supporting shuttle launches. But only a year later, the number was revised further downward, to only four Vandenberg launches per year. That number may have fluctuated upwards in the following two years as the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) evaluated the possibility of using the shuttle as a crewed reconnaissance platform, carrying a camera system known as DAMON. (DAMON was an inside joke among some at the NRO who were fans of “Star Trek” and were referencing an episode featuring the Nomad space probe—“Damon” is “Nomad” spelled backwards; see “Top Secret DAMON: the classified reconnaissance payload planned for the fourth space shuttle mission,” The Space Review, July 1, 2019, and “The NRO and the Space Shuttle,” January 31, 2022.)

The plan was to launch the shuttle from the mothballed Space Launch Complex 6, known as “Slick-6.” Slick-6 required extensive new construction to handle the shuttle. (credit: USAF) |

Slick-6 and MOL

It was relatively clear from the early discussions of a West Coast shuttle launch capability that a large unused pad facility at Vandenberg, Space Launch Complex 6, SLC-6 or “Slick-6,” was the most likely first pad for the space shuttle. SLC-6 had been mothballed since 1970, soon after construction was completed.

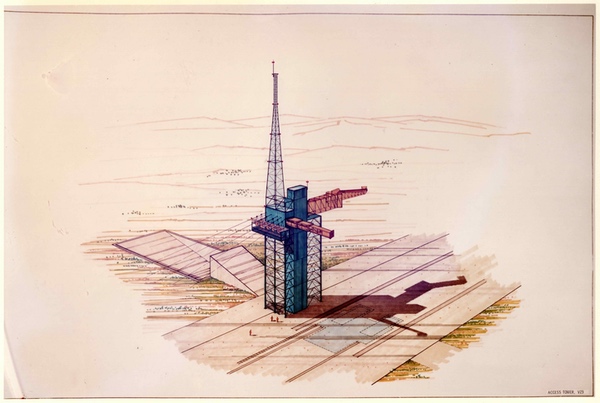

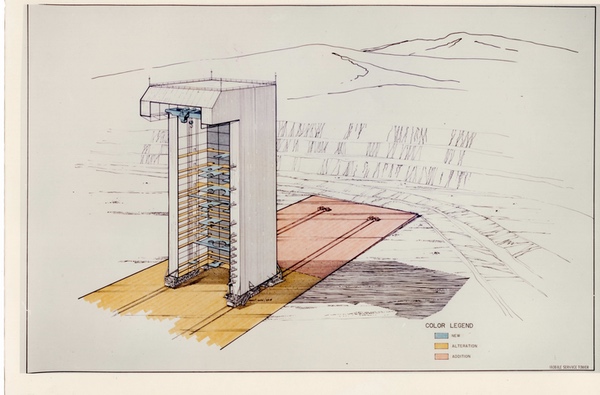

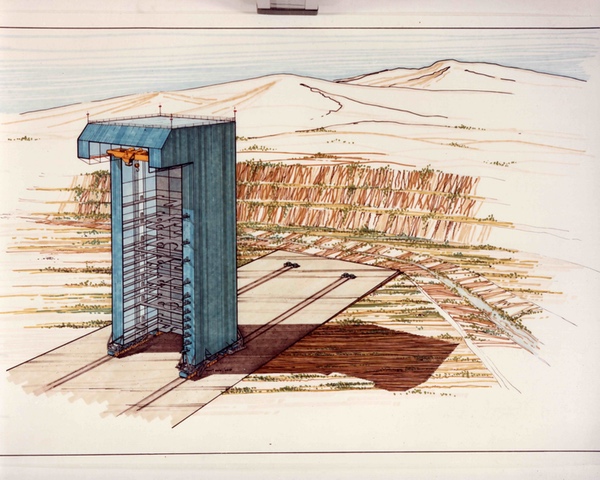

Artwork depicting the proposed access tower for the shuttle. Unlike the Kennedy Space Center launch complex, the shuttle would be erected at the launch site and the protective buildings would be moved away from the pad for launch. (credit: USAF) |

In the mid-1960s, the Air Force needed to build a new facility to launch a powerful rocket it was developing to launch the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) into polar orbit. The Titan IIIM was bigger than other Air Force rockets and would lift off from Vandenberg and head south over the Pacific Ocean. Vandenberg already had numerous launch pads, but none was suitable for the Titan IIIM, and so the Air Force decided it needed to expand Vandenberg to the south of the existing base, taking land that was owned by the Sudden family, who owned vast amounts of territory in California used for farming and ranching. The Air Force used eminent domain to take the land, but was soon sued by the Suddens, who claimed that they were not properly compensated for their property. They won in court and the Air Force had to pay significantly more for the land.

The payload changeout room would be mounted on rails and would move away from the pad. (credit: USAF) |

By 1968, the Air Force began construction on the Titan IIIM launch pad facility, which was soon designated Space Launch Complex 6. Slick-6 not only included the pad and tower and fueling equipment common to other launch pads on the base, but also payload processing and crew quarters for the MOL astronauts. Because it was far from the main base, Slick-6 had to be more self-contained than other pads. But because it was squeezed between a low mountain and the ocean, it was more cramped than generally desirable for a launch complex, meaning that an explosion during launch could damage nearby structures.

The mobile service tower was adapted from an existing structure but would have to move back farther from the pad for launch. (credit: USAF) |

Construction on Slick-6 proceeded until summer 1969 when the MOL program was abruptly canceled. The facility was nearly complete, and the Air Force obtained permission to finish construction, which was mostly done by early 1970. At that time Slick-6 was placed into inactive “mothball” status and sat unused throughout the rest of the 1970s. Other than local wildlife and curious base personnel, the only significant visitors to the facility came in 1977 when a Hollywood film crew for the NBC television show “The Bionic Woman” filmed part of an episode on the property.

The mobile service tower was adapted from an existing structure but would have to move back farther from the pad for launch. (credit: USAF) |

The Space Shuttle and Slick-6

After a site review, Slick-6 was formally selected as the shuttle launch complex. Air Force estimates indicated that although substantial infrastructure was already located there, the conversion costs would be high. This prompted a review by the General Accounting Office, which initially determined that a West Coast launch site for the shuttle was unnecessary and the shuttle could instead perform all launches, including over the North Pole, from Florida. That conclusion was rejected by the Defense Department and by the early 1980s construction began at Slick-6 to convert it to the shuttle’s requirements. In 1975 the goal had been for operational capability at SLC-6 by 1982, but program managers never considered this schedule realistic.

This large model of Space Launch Complex 6 was built when the facility was converted to support the Delta IV rocket in the early 2000s. It lights up to show how the rocket is moved to the pad.

(credit: Author's photo) |

The construction project at Space Launch Complex 6 during the early 1980s was the largest the base had seen in a long time. Although some buildings and structures at the site remained, construction crews began massive excavations to enlarge the flame trenches to accommodate the space shuttle’s exhaust. They poured thousands of tons of concrete. Multiple new structures had to be built at the complex to support the unique requirements of the shuttle. For instance, none of the structures could touch the shuttle because they could damage it in event of an earthquake. Early Air Force plans to stack the shuttle components outdoors had to be revised when it became apparent that local weather conditions required that the shuttle be protected by a structure from the elements.

As work on SLC-6 continued during the early 1980s, construction crews also began erecting structures and pouring concrete at several other locations at Vandenberg. Those projects will be discussed in part 2.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.