National Reconnaissance Program crisis photography concepts, part 4: FASTBACK and FASTBACK-Bby Joseph T. Page II

|

| FASTBACK was an intriguing—yet fundamentally dangerous—way to send a reconnaissance satellite system into orbit. |

The FASTBACK design consisted of a relatively small, quick reaction photo-satellite system, launched on-call from Johnson Island in the Pacific. An example mission would have one or two accesses (prime orbital paths) over a target area depending on location and selected inclination. After the photographic mission was complete, the satellite recovery vehicle would splash down in the Atlantic. Hard copy photographic processing would commence in the Washington DC area within 24 hours from launch decision.

Martin Marietta’s FASTBACK was designed with the following crisis reconnaissance capabilities in mind:

- Rapid response, providing Washington DC leaders high quality imagery in less than 24 hours.

- Geographic access, covering a considerable portion of the globe where crises were historically likely to occur.

- Image quality, planning for 3.3-feet (1 meter) of ground resolution at nadir from a 45-inch (114-centimeter) rotating optical bar camera.

- Target coverage, with the ability to cover 10,000 miles (16,000 kilometers) along track and a 130-nautical-mile (240-kilometer) swath width

- Weather avoidance, due to rapid launch capability

- Low cost, using surplus Minuteman rocket motors

- Low vulnerability, due to short mission durations

The key to FASTBACK’s rapid launch capability was the use of a refurbished Minuteman ICBM, with an additional fourth stage consisting of an orbital inject motor on the spacecraft.

Ace in the hole at Johnston Atoll

Defined by General Operating Requirement 171 from August 1959, the then designated Strategic Missile 80 (SM-80) Minuteman ICBM was designed for quick-reaction strategic bombardment from underground hardened launch sites in the continental United States. The first-generation Minuteman missile (LGM-30A and LGM-30B) was a three-stage solid-fueled ICBM, substantially smaller than the Atlas or Titan boosters used within the NRP launch manifest. Minuteman’s strongest characteristic—driven by its solid-fuel design—was the ability to launch within seconds after receiving the fire order. This quick-launch feature was critical for the nuclear deterrence mission but held added benefit for the FASTBACK design, allowing mission start and completion to recovery within a 24-hour timeframe.

| The key to FASTBACK’s rapid launch capability was the use of a refurbished Minuteman ICBM, with an additional fourth stage consisting of an orbital inject motor on the spacecraft. |

The original basing concept for the Minuteman ICBM placed individual missiles (“sorties”) into hardened underground launch facilities (colloquially known as “silos”) separated into organizational units of ten. While the FASTBACK concept document did not provide details about the launcher mode, the familiar underground silo launch described in the Minuteman operating concept would have been extremely unlikely for two reasons: required access to the satellite payload before launch and the geology of Johnston Atoll.

Pitstop in the middle of nowhere

Aficionados of space and missile history will recognize the name of Johnston Island (or alternatively Johnston Atoll) as the location of high-altitude nuclear testing during the 1960s Operation FISHBOWL and the Air Force’s nuclear-tipped Program 437 anti-satellite program in the mid-1970s. Before its use in nuclear testing, the island’s location in the Pacific Ocean was known to the Western world as early as 1598, when Dutch sailors ventured past the atoll while searching for sea routes to Japan.

The island was infrequently visited over the centuries, yet came to minor prominence after the passing of the Guano Act in 1856, which authorized American citizens to claim unoccupied islands in the name of the US for the purpose of obtaining guano (bird or bat excrement). Several centuries of large bird populations living on the island left tons of guano, an excellent source of phosphates and ammonium compounds critical for the manufacture of explosives and fertilizer.

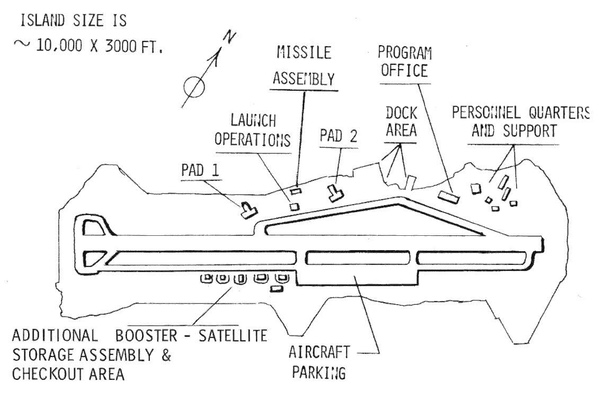

Figure 2: Layout of Johnston Island for proposed FASTBACK operations. (credit: NRO) |

Johnston Island fell out of public notice after World War II and administration of the island facilities transferred to the Air Force in mid-1948. After the development of the thermonuclear bomb, Johnston Island became an important center for the HARDTACK and DOMINIC series of nuclear tests. The DOMINIC series saw the buildup of rocket launch facilities on the island, namely shelters and pads for the Thor Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) system. After atmospheric nuclear testing ceased in 1962, Johnston Island contained the world’s first operational nuclear-tipped anti-satellite system, Program 437, until those facilities were destroyed by Hurricane Celeste in August 1972. At the time of FASTBACK’s consideration in the early 1970s, however, Johnston Island did have launch control and pad access available.

Spacecraft and camera

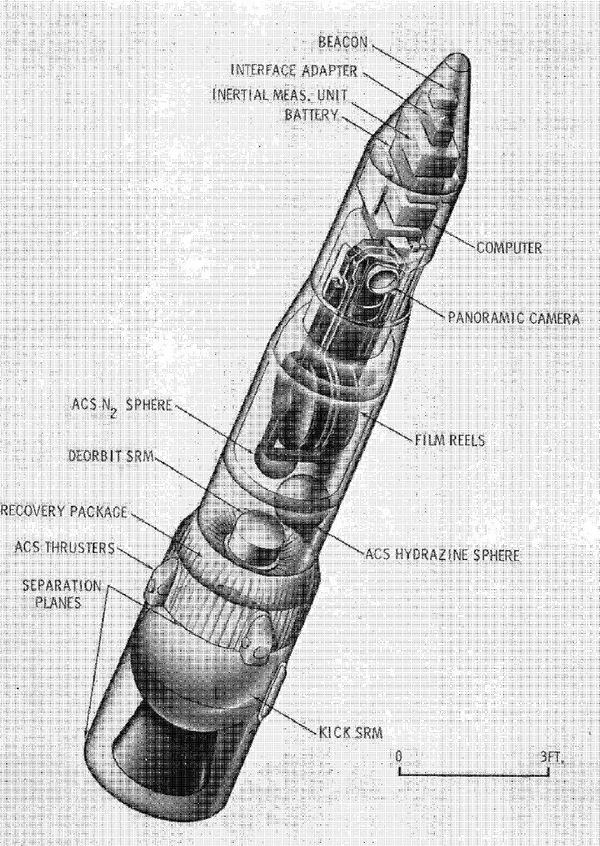

The spacecraft was conceived as being 16 feet (4.9 meters) long. with a Thiokol TE-M-364-2 orbital kick motor weighing approximately 2,600 pounds (1,180 kilograms). The spacecraft base diameter was measured at 37.5 inches (95.3 centimeters) to be compatible with the third stage of the Minuteman booster.

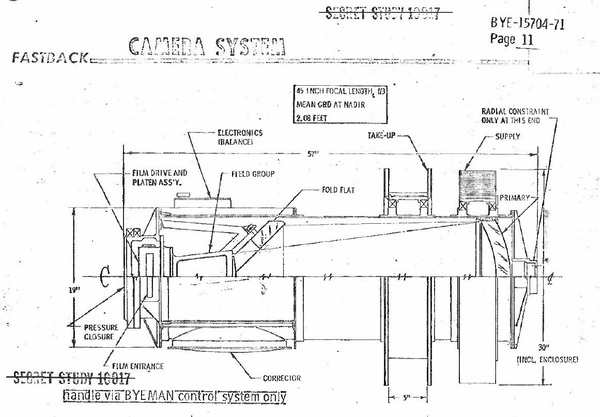

Figure 3: Proposed FASTBACK camera system. (credit: NRO) |

The front portion of the panoramic optical bar camera would rotate about its longitudinal axis at 45 rpm with a scan angle of plus or minus 45 degrees, equating to a ground swath of 130 nautical miles. The optical package was estimated to provide a ground resolution of 3.3 feet at nadir. ITEK provided designs about an “as-built” aircraft camera, stating that no state-of-the-art techniques were required, negating additional funding or development time for novel or bespoke technologies. After recovery, the spacecraft and camera assembly could be refurbished for future usage, bringing down proposed operations costs by one third.

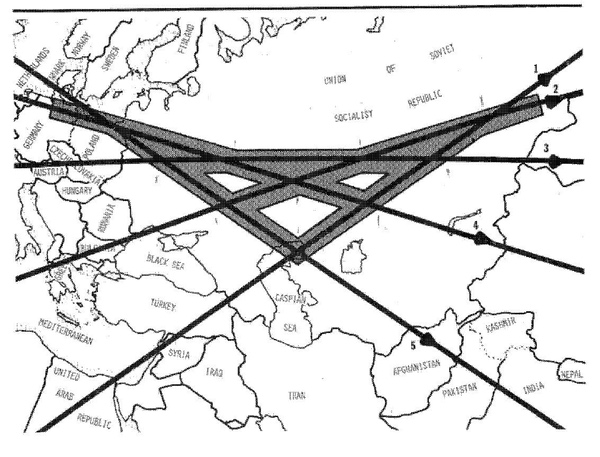

Figure 4: Orbital tracks illustrative of FASTBACK’s proposed coverage from Johnston Island launch. (credit: NRO) |

Ground coverage

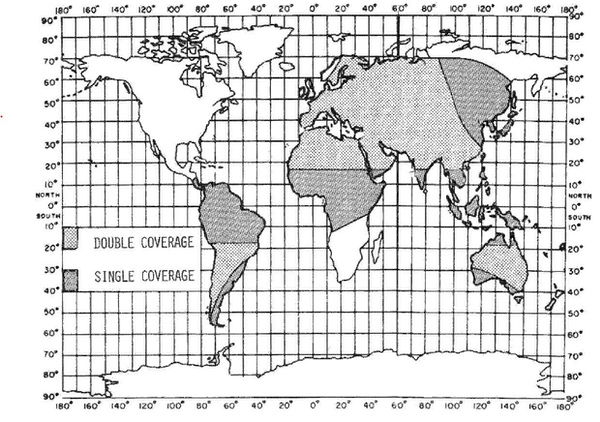

An example mission launched on an inclination of 55 degrees with an elliptical orbit of 65 by 300 nautical miles (120 by 555 kilometers) is shown in Figure 4. The image shows the area of concentrated (targeted) coverage, and opportunities for single coverage of long tracks during each orbit revolution. The limiting factor on these single coverage “targets of opportunity” is the area illuminated by sunlight. The FASTBACK camera’s “fire and forget” guidance used preprogrammed timing for target photography, lessening the ability of ancillary target collection along the swath underneath the planned orbital track. This could be overcome by additional sorties launched with different inclinations, thereby changing the target track. Within Johnston Island’s possible launch inclinations (between 17 and 70 degrees), the location of concentrated coverage is listed in Figure 5.

Figure 5: FASTBACK’s proposed areas of single and double coverage during one mission. (credit: NRO) |

Recovery operations

Planned recovery operations for FASTBACK conceptually used systems in place for other NRP efforts, namely the JC-130s from the 6594th Recovery Control Group (later renamed the 6594 Test Group on July 1, 1972). The group was stationed in Hawaii due to their Pacific Ocean area of operations, though for the FASTBACK launches group aircraft would be based in Bermuda for an Atlantic Ocean catch.

| If a country wants to maintain a balance of terror, without tipping over into nuclear conflict, no one should consider using well-known nuclear delivery systems for other purposes, especially during times of crisis and hair-trigger responses. |

A fleet of five aircraft would be deployed for each recovery operation over an area of 300–500 nautical miles (555–925 kilometers) in-track by 100 nautical miles (185 kilometers) cross-track. This large area would be significantly lessened with tracking transponders. Once the reentry package was recovered, the JC-130s would fly to Andrews AFB, Maryland. After sending the film to Rochester, New York for development, finished images would go to the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) in the Washington DC area for analysis.

Ground zero for World War III

For an island that was originally known for enormous stores of bird poop, Johnston Island stood on the edge of infamy for its role in nuclear testing and housing Program 437. The decision to use the facilities there for FASTBACK made logical sense when attempting greatest photographic coverage for a crisis reaction system. However, the use of a modified Minuteman missile—a known nuclear weapon carrier—at a location that was known for nuclear activities did not seem to create a stir in the system developers.

Figure 6: FASTBACK Launches or a Minuteman mass raid? Who could tell… (credit: Warner Bros.) |

While the Soviet Union’s early warning satellite system “OKO” did not launch until the mid-1970s, it is logical to presume FASTBACK’s presence through its Minuteman launch vehicle would have increased monitoring of Johnston Island by Soviet SIGINT ships. One question brought up by using known nuclear-related systems for non-nuclear operations (such as the AGM-86D Conventional Air-Launched Cruise Missile or BGM-109 Tomahawk missile): Can an adversary tell if the strike is using conventional high explosives or will the blast be large, loud, and create a mushroom cloud?

The obvious answer to this rhetorical question should be “no,” mainly for the element of surprise against an adversary. But if a country wants to maintain a balance of terror, without tipping over into nuclear conflict, no one should consider using well-known nuclear delivery systems for other purposes, especially during times of crisis and hair-trigger responses.

“B” means “Better”: FASTBACK and data return

A second variant of the system, designated FASTBACK-B, was proposed for use within the NRP, differentiated from the original FASTBACK with the inclusion of a digital data-return system through the Air Force Satellite Control Network (AFSCN). Where FASTBACK used a film-based camera, returning images to Earthy via a reentry system, FASTBACK-B incorporated on-board film development and a laser scanner read-out system that would beam digital images to ground users without having to wait for film return and subsequent development.

| The ingenuity of using recycled Minuteman ICBM rocket motors stands out as a dangerous gamble to an armchair historian looking through the rearview mirror of history but may have been a calculated risk to prevent conflicts leading up to World War III. |

Other significant differences with the FASTBACK-B concept included a different, but not better, launch site (explained below), extended on-orbit time of up to 30 days, and planned use of polar orbits versus the high inclination ones available from Johnston Atoll. Photographic swath width shrinks to 100 nautical miles, while the in-track imaging is limited to 4,600 square nautical miles (15,800 square kilometers) based on film storage capacity limits. Analog photograph conversion into digital bits occurs via a satellite-based wide-bandwidth laser scanner and ground transmission reception to the Vandenberg Tracking Station (COOK) or the New Hampshire Tracking Station (BOSS).

The launch location for FASTBACK-B is listed as the Western Test Range, but the only infrastructure within the range to launch Minuteman missiles was at Vandenberg AFB. The same rhetorical questions about confusing nuclear and non-nuclear systems may not be considered from a Vandenberg launch, due to the base purportedly only launching unarmed Minuteman test missiles over its decades-long history. However, one question would stand out to any launch observer off the coast of California or in the foothills surrounding the base: why is an “unarmed” Minuteman missile being launched northward, and not westward toward the Pacific Ocean test site at Kwajalein?

Questions abound from casual observation would have pulled back the veil of security during the first (and likely last) FASTBACK-B launch from Vandenberg, killing the system before it could operate effectively.

The rearview mirror of history

The FASTBACK and FASTBACK-B concepts continued the trend of innovation for companies and engineers looking to bolster the NRP’s capabilities during crisis reconnaissance operations. The ingenuity of using recycled Minuteman ICBM rocket motors stands out as a dangerous gamble to an armchair historian looking through the rearview mirror of history but may have been a calculated risk to prevent conflicts leading up to World War III. Regardless of the aborted developmental outcome of the FASTBACK series, system characteristics created for rapid reconnaissance, in both launch and information recovery, wove common threads throughout these developmental designs, eventually leading to the ultimate “winner” of the much-needed crisis reconnaissance system: the KENNEN electro- optical system.

References

- No Author. “Should The NRO Acquire an Interim System with Improved Response Time Prior To EOI?” Issue Paper. NRO For All 2022. C05096641. 1971.

- Martin Marietta. FASTBACK: A Fast Response Photographic Reconnaissance System. November 1970. NRO FOIA For All Collection.

- Hofmann, Frederick. Memorandum for the Record: Martin Company Briefing on FASTBACK. 16 November 1970. NRO FOIA For All Collection.

- Martin Marietta. “The FASTBACK B Vehicle: A Fast Response, Low-Cost Photo Reconnaissance System.” 26 March 1971. NRO FOIA For All Collection.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.