Countering threats to US commercial space systemsby Marc Berkowitz

|

| Russia is targeting and deliberately interfering with US commercial space systems that Ukraine is employing to support its self-defense and asserts they are legitimate military targets. |

This article examines how to counter threats to US commercial space systems. It discusses the commercial space marketplace, US policy regarding commercial space activities, the government’s interest in leveraging commercial space capabilities for national security, the threat to commercial space assets and operations, and alternative approaches for their protection and defense. It concludes by recommending how and when to protect and defend commercial space systems and assure they will continue to contribute to America’s economic and national security.

Commercial space marketplace

The commercial space market is robust and vibrant, with a mix of traditional, non-traditional, and new entrants, an expanding number of market segments, and increasing economic value. Indeed, the global space economy is forecast to grow from about $469 billion to more than $1 trillion by 2030. American private enterprises are the primary catalyst for this growth.

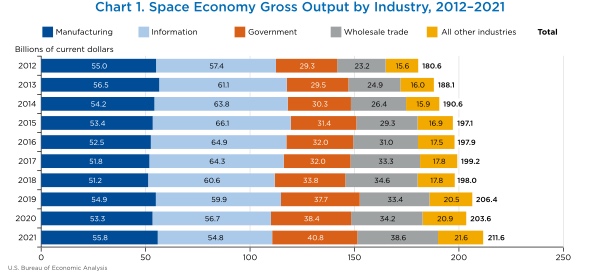

The United States is the global leader in space investment, innovation, and invention. American private investment now exceeds that of the public sector in most areas of space research and development. As evidenced by the most recent US government data, the US space economy accounted for $211.6 billion of gross output, $129.9 billion (0.6%) of gross domestic product, $51.1 billion of private industry compensation, and 360,000 private industry jobs in 2021 (Figure 1).[1]

Figure 1: Space Economy Gross Output, 2012–2021 |

Another indicator of the vibrancy of the commercial space market is the investment startup space ventures were able to attract. Such ventures begin as angel or venture capital-backed new starts. They differ from startup ventures from aerospace and defense contractors and large, publicly traded space companies. According to a study by Bryce Technologies, space startups attracted approximately $8.2 billion in total financing in 2022 despite the global economic downturn which prompted reduced venture funding across all industries.[2] . This involved 154 deals, more than 400 investors, and 123 companies based in more than 20 countries. The average size of the deals was $53 million and seven were more than $100 million. These involved SpaceX and accounted for $2.2 billion out of the $8.2 billion.

The international commercial space marketplace consists of both mature and emerging market segments. The mature segments are launch services, telecommunications, Earth observation, and navigation. Emerging segments include space situational awareness, tourism, in-space servicing and manufacturing, and resource extraction. The commercial or private space sector is one of four sectors in the United States’ space enterprise. The other three are federal government sectors (defense, intelligence, and civil) that interact with and regulate the commercial sector. In fact, the US government is concurrently a regulator, investor, and consumer of the commercial goods and services supplied by the private sector.

US Space Policy

US policy defines “commercial” space as goods, services, or activities provided by private sector enterprises that bear a reasonable portion of investment risk and responsibility, operate in accordance with typical market-based incentives for controlling cost and optimizing return on investment, and have the legal capacity to offer goods or services to existing or potential nongovernmental customers.[3] Presidential guidance directs that the US government shall support and enhance the international competitiveness of America’s space industry, use commercial goods and services to the maximum extent practicable, except for national security, foreign policy, or public safety reasons, and not compete with the commercial space sector.[4]

In addition, the US government has endeavored to streamline regulations on the commercial use of space. Presidential guidance directs the reform of the Executive Branch’s commercial space regulatory framework to ensure America is a leader in space commerce.[5] This includes commercial space transportation regulations, commercial remote sensing regulations, radio frequency spectrum management, and export licensing regulations.

US policy has succeeded in enabling the growth of commercial space activities. In addition to strengthening the US economy with jobs, technology, trade, and revenue, this creates opportunities to leverage the commercial space sector for US national security. Such opportunities include reforming government space acquisition practices and processes; accelerating capability delivery; accessing new sources of innovation and invention; saving or avoiding costs; focusing government investment on unique and/or advanced defense and intelligence capabilities; using competition as a catalyst for improved space capability, affordability, and agility; improving inter-sector relationships regarding resilience, protection, and defense of critical space missions and assets; and enhancing space mission resilience and the deterrence of aggression.[6]

Leveraging commercial space for national security

Commercial space is one of America’s main asymmetric advantages in the ongoing astropolitical competition. Consequently, the US national security space community has embarked on creation of “hybrid” (government and commercial) architectures that leverage space capabilities designed, developed, and produced by both the traditional aerospace and defense industry as well as new commercial enterprises to field systems rapidly, increase opportunities for technology insertion, and enhance the resilience of the national security space force structure and posture. Considering America’s reliance on space for both economic and national security as well as the array of threats posed to space systems, it is prudent to leverage the commercial space sector’s financial resources, technical innovations, and entrepreneurial skill, while managing the potential risks of doing so.

| The US government and the private sector must determine how much protection is required, under what circumstances, and for how long. Different degrees of protection may satisfy different mission needs. |

Indeed, recognizing that it will be more resilient and capable if it combines organic capabilities with the capabilities from other providers, the US Space Force recently issued a Commercial Space Strategy to “leverage the commercial sector’s innovative capabilities, scalable production, and rapid technology refresh rates to enhance the resilience of national security space architectures, strengthen deterrence, and support Combatant Commander objectives in times of peace, competition, crisis, conflict, and post-conflict.”[7] Consistent with this strategy, the Space Force will consider commercial support for space domain awareness; satellite communications; space access, mobility and logistics; tactical surveillance, reconnaissance, and tracking; environmental monitoring; cyberspace operations; command and control; and positioning, navigation, and timing.[8] It will not seek commercial support for missile warning, combat power projection, electromagnetic warfare, and nuclear detonation detection.[9]

Similarly, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) is pursuing a hybrid approach to its future intelligence space architecture.[10] As Dr. Troy Meink, the NRO’s principal deputy director, stated that the NRO sees value in leveraging new commercial capabilities for certain missions where small satellites can meet requirements at lower cost. The NRO has issued contracts for electro-optical, radar, radio frequency, and hyperspectral imaging contracts for the acquisition of commercial data.[11] 11

The Department of Defense (DoD) defines “protection” as “preservation of effectiveness and survivability of mission-related personnel, equipment, facilities, information, and infrastructure deployed or located within or outside the boundaries of a given operational area.”[12] Defense, security, survivability, assurance, operational continuity, and resilience, however, have all been used by US government officials as synonyms for protection. There are, of course, different degrees of protection that can be provided to commercial space systems. Not all forms of protection are equivalent. The US government and the private sector must determine how much protection is required, under what circumstances, and for how long. Different degrees of protection may satisfy different mission needs. Required levels of protection should be driven by mission, threat, vulnerability, and available alternatives.

The US government has long declared that unimpeded access to and use of space is a vital national interest because of its overriding importance to America’s safety, integrity, and survival.[13] US space policy states that space systems are sovereign property with the right of passage through and operations in space without interference.[14] “Purposeful interference,” with space systems, including supporting infrastructure, is an infringement on US sovereign rights.[15] The United States may respond to such interference at a time, place, and manner of its choosing, including with the use of force, consistent with its inherent right of self-defense.[16]

Despite this declaratory policy, the US government either has not responded or only issued diplomatic demarches in response to the increase in such purposeful interference incidents. The DoD only amended its space policy to state that it would protect and defend such assets if directed by the Secretary of Defense or other appropriate authority.[17] DoD’s Commercial Space Integration Strategy states that “in general, the Department will promote the security of commercial solutions through three lines of effort: norms and standards, threat information sharing, and financial protection mechanisms.”[18] In this regard, US Space Command, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, and NRO established a “Commercial Space Protection Tri-Seal Strategic Framework” to jointly share threat information to avoid or reduce harm to commercial satellites from potential threats.[19]

Threat to commercial space assets and operations

The geopolitical competition has extended to near Earth space and may expand to cislunar space, the region beyond geosynchronous Earth orbit and the Moon’s surface. The astropolitical dimension of the conflict has prompted the current and growing threat to US national interests in space. Adversaries have developed, tested, fielded, and operate anti-satellite (ASAT) or other offensive space control weapons systems to contest freedom of passage through and operations in space. Whether they are owned and operated by governments, international consortia, or commercial enterprises, spacecraft are being held at risk. As then-Vice Chief of Space Operations General David Thompson stated, “both China and Russia are regularly attacking U.S. satellites with non-kinetic means, including lasers, radio frequency jammers, and cyber-attacks.”[20]

Russia and China see space as a domain where the United States can be coerced given its dependence upon vulnerable space systems. They are pursuing an array of cyber, electronic warfare, kinetic energy, directed energy, nuclear, and orbital counterspace weapons.[21] Indeed, the White House recently confirmed media reports that Russia has developed and is preparing to deploy a nuclear-armed ASAT weapon on-orbit.[22] Similarly, Iran and North Korea have cyber, electronic warfare, and missile capabilities which can interfere with space assets and operations.[23]

The value of space systems for prestige, influence, knowledge, wealth, and power is what makes them lucrative targets. Political, symbolic, and economic as well as dedicated defense and intelligence space assets thus may be attacked. Conflict may begin in or extend to space to undermine US military combat effectiveness, intelligence collection, economic prosperity, societal cohesion and morale, and political resolve.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict highlights the increasing value and utility of commercial space operations for US and international security.[24] It also underscores the associated risk of being considered military targets by adversaries. Months prior to the invasion, Russia conducted a destructive test of a direct-ascent kinetic-energy ASAT. The test generated thousands of pieces of orbital debris that endangered both American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts on the International Space Station as well as harmed space environmental sustainability (Figure 2).[25]

Figure 2: Orbital Debris Track From Russian Kinetic Energy ASAT Test[26] |

While it prompted international opprobrium, the ASAT test served as a clear warning of Russia’s ability to hold key satellites at prompt risk of destruction.

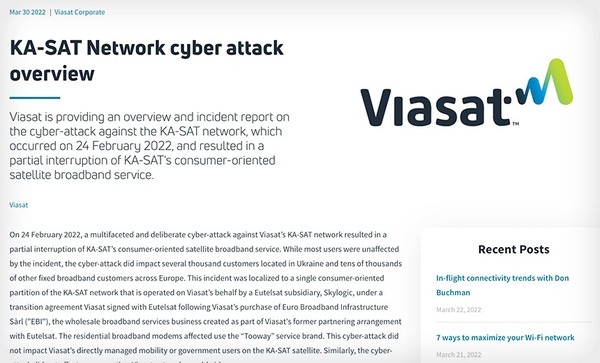

Moreover, Russia engaged commercial and civil space systems as a precursor to their large-scale invasion and during subsequent kinetic combat operations. An hour before the invasion, Russia launched a targeted denial of service cyberattack against Viasat’s KA-SAT ground network (Figure 3).[27]

Figure 3: Viasat’s KA-SAT Cyber-attack Summary[28] |

It has also repeatedly attempted to interfere with SpaceX’s Starlink satellite internet services.[29] In addition to commercial satellite Internet and telecommunications services, Russia jammed civil satellite positioning, timing, and navigation services with electronic warfare systems (Figure 4).[30]

Figure 4: Russian Zhitel and Tirada-2 Electronic Warfare Systems[31] |

In an ex post facto justification, a senior Russian Foreign Ministry official asserted that commercial assets are legitimate military targets. Konstantin Voronstov, deputy director of the Department for Non-Proliferation and Arms Control, said at the United Nations that:

I would like to draw special attention to the extremely dangerous tendency, which has surfaced in the course of the developments in Ukraine. I mean the use of outer space civil infrastructure facilities, including commercial ones, in armed conflicts by the United States and its allies…Quasi-civil infrastructure may be a legitimate target for a retaliation strike. [32]

Similarly, Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova said, “We are aware of Washington’s efforts to attract the private sector to serve its military space ambitions … [such systems] become a legitimate target for retaliatory measures, including military ones.”[33]

| The US government’s renewed interest in leveraging commercial space capabilities for national security will heighten the risk that commercial space assets operations will become military targets. |

As evidenced by Russian words and deeds, they are not inhibited in targeting commercial systems that are US sovereign property and being employed by numerous countries besides Ukraine. Russia clearly recognizes that third-party space systems not owned or operated by their adversary can impact the course and outcome of the conflict. Consequently, they are conducting sustained non-kinetic offensive space control operations for area denial and force protection.

The US government’s renewed interest in leveraging commercial space capabilities for national security, especially integrating commercial goods and services into hybrid architectures with both government and private sector capabilities, will heighten the risk that commercial space assets operations will become military targets. Consequently, all approaches for how to protect commercial space systems must be considered.

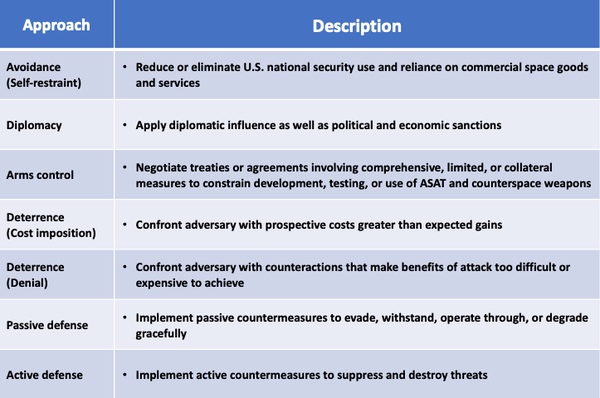

Protection and defense alternatives

There are numerous options for protecting and defending commercial space systems. As shown in Figure 5, these range from avoidance to active defense. Options vary, among other things, in terms of practicability, cost, and likelihood of success. None are mutually exclusive. While they could be implemented independently, a course of action with a combination of options is more likely to create synergistic benefits and be effective.

Figure 5: Options for Protecting and Defending Commercial Space Systems |

Avoidance, self-restraint, or strategic evasion would entail the US government greatly reducing or eliminating its use of, and reliance upon, commercial space goods and services for defense or intelligence purposes. The benefit of avoidance is that it could undercut an adversary’s motive for holding at risk and attacking commercial space systems. Its disadvantages are its impracticability as well as that an adversary may not believe America will not rely upon commercial space capabilities that have dual (civil and national security) uses and might target commercial assets anyway because of the impact of disrupting or eliminating their services.

Diplomacy involves negotiating with foreign nations or non-nation-state actors on tacit or formal agreements to protect commercial space systems. It can also involve bringing pressure, for example, through political or economic sanctions, to persuade a belligerent to adopt a policy of not interfering with commercial space systems providing services to non-combatants prior to hostilities or stop doing so if already engaged in hostilities. The advantages of diplomacy are that is it the lowest-cost option and may help to legitimize or provide political top cover for other approaches. Its disadvantages are an unfavorable track record and opportunity costs. Diplomatic initiatives may be unpersuasive, and sanctions may be ineffective as well as impose financial burdens on the US, its allies, and friends.

Arms control involves negotiating measures to prohibit or constrain the development, testing, or use of ASATs and counterspace weapons to minimize the costs and risks of a space arms competition or conflict involving space, as well as limit the scope and intensity of violence in the event of war. The advantages of space arms control are that it could inhibit or reduce the threat as well as the cost of defensive preparations. Its disadvantages include creating opportunities for adversaries to conduct political and legal warfare (lawfare), the problem of defining what constitutes a weapon, the variety of threats against space systems, dual-use technology, verifying compliance, and enforcement.

Deterrence by cost imposition, punishment, or retaliation entails confronting an adversary with prospective costs greater than expected gains.[34] Punitive threats could involve military action, economic sanctions, diplomatic penalties, or other measures that will punish or thwart the adversary if it does not comply. The advantage of deterrence by cost imposition is that it may restrain an adversary from threating or using force against commercial space assets. Its disadvantage is that it may fail. The opponent may not perceive the threat is credible, it may not be sufficient to produce restraint, the adversary also may be able to absorb the punishment, be willing to risk escalation, or, if the decision-maker is insane, a religious zealot, or terrorist, literally may be “beyond deterrence.”

| The US government should implement a comprehensive approach that integrates diplomacy, threat awareness, deterrence (by denial and cost imposition), as well as passive and active defenses to protect commercial space systems. |

Deterrence by denial involves acquiring and fielding capabilities and preparing potential counteractions that would make the benefits of attacking commercial space assets and operations appear too difficult or expensive to achieve.[35] Denial of benefits can be accomplished with defensive measures. The advantages of deterrence by denial are that it not only may inhibit or reduce the threat, but it also provides a hedge against deterrence failure. Its disadvantages are that it may not be effective if the threat is perceived as incredible, the adversary is willing to risk escalation, or is beyond deterrence.

Passive defenses involve measures to evade, withstand, operate thru, or degrade gracefully against ASAT or counterspace weapons effects. Such countermeasures include, for example, physical security, infrastructure protection, backups, autonomy, encryption, hardening, and proliferation.[36] The advantages of passive defenses are that they can counter specific types of weapons systems and effects, enable deterrence by denial, and hedge against deterrence failure. Its disadvantages are penalties of increased size, weight, or cost of acquiring and operating the satellite system.

Active defenses involve fielding military capabilities to suppress and destroy threats to space assets. The authority to “shoot back” at threats to commercial assets either could be retained by uniformed military personnel or the government could issue “letters of marque and reprisal” to allow private persons to conduct active defense or launch counterattacks against the space weapons of a foreign nation.[37] The advantages of active defenses are that they enable deterrence by denial, inhibit or reduce the threat, and hedge against deterrence failure, and limit damage. Its disadvantages are cost and concerns about “weaponizing” space.

Recommendations

Outer space is an increasingly complex and dangerous operating environment for government and commercial space systems. In order to determine the best mix of non-materiel and materiel solutions to address the threat to US vital national interests in space, the DoD should conduct rigorous, objective, data-driven analytic decision support to inform force design and acquisition decisions, including where commercial goods and services fit in national security space force structure and posture. Decisions regarding the employment of commercial capabilities for national security purposes should be based on multidisciplinary system engineering, architecture, economic, and operational analyses.

Such analyses should be used to determine mission utility, mission-critical dependencies, operational risks, vulnerabilities, costs, and policy implications that reliance or dependence upon commercial space systems would entail so the government can “use the right tool for the job.” In addition, the President, Secretary of Defense, and Director of National Intelligence should provide direction regarding the acceptable extent of reliance or dependence on commercial space capabilities for defense and intelligence space missions. This could range from deconfliction and coordination, to augmentation and integration, all the way to federation or interdependence.

Based on the aforementioned decision support and direction, the US government should implement a comprehensive approach that integrates diplomacy, threat awareness, deterrence (by denial and cost imposition), as well as passive and active defenses to protect commercial space systems. This includes fielding a dynamic, layered, defense in-depth with a mix of passive and active defenses to evade, withstand, operate through, degrade gracefully, suppress, and destroy threats to space systems. Such a defense in-depth will help to thwart an attack with successive layers and multiple countermeasures at each layer to defeat threat kill chains, rather than relying on a single line of defense.

The federal government should incorporate this comprehensive approach into declaratory policy statements and diplomatic engagements to convey US national interests and the stakes that would be involved in a conflict in the space domain to deter adversaries as well as reassure allies and partners. In addition, the President should provide guidance to the Director of National Intelligence to assess foreign capabilities and intentions regarding threats to commercial space assets and operations. The President should also provide guidance to the Secretary of Defense to prepare operations and contingency plans as well as rules of engagement, thresholds, and triggers for protection and defense of US citizens, property, and commercial assets as well as non-US forces, and foreign nationals or property in space.

The Secretary of Defense should then direct the combatant commanders to incorporate such protection and defense in their development of critical asset lists and defended asset lists. Policy reviews of war plans as well as war games and exercises should be conducted to evaluate such rules of engagement, thresholds, triggers., and defensive priorities. This will require the US government to determine what constitutes hostile actions and declarations of hostile intentions involving space systems. In comparison to a nuclear detonation or a kinetic strike in space, non-kinetic acts may not necessarily constitute an armed attack under international law. At what point (in scale, duration, or effect), for example, should electronic warfare jamming or spoofing be considered a hostile act?

Additionally, it will be up to the President and Congress to decide, given the circumstances, interests, stakes, and risks, whether deliberate interference with a dual-use commercial system is considered a casus belli or act or war, like the sinking of the Lusitania that killed 1,195 people, including 123 Americans, in 1915, or whether it does not, as is the case thus far during the Ukraine conflict. DoD can communicate America’s resolve to protect and defend commercial space assets via diplomatic exchanges, experiments, tests, demonstrations, exercises, deployments, and operations.

Moreover, the US government should exercise its influence on the commercial space sector as the monopsonist in the federal space marketplace. In this regard, federal departments and agencies must leverage and align the government’s roles vis-à-vis the commercial space sector as a regulator, consumer, and investor. They should engage the commercial space sector with a mix of incentives, inducements, and requirements to increase the protection of their goods and services. This should include financial investments in innovative capabilities, increased procurements of commercial space goods and services, classified information sharing, contractual mandates for traditional commercial insurance, commercial war risk insurance, or government provided insurance or indemnification, and requirements for selected threat countermeasures.

| Federal agencies should engage the commercial space sector with a mix of incentives, inducements, and requirements to increase the protection of their goods and services. |

The US government can educate the private space sector and foster its enlightened self-interest, among other things, by increasing the sector’s threat awareness via routine information sharing and space domain awareness support of commercial operations. It can also increase its collaboration with the private sector to contract for and utilize commercial systems, information, and analytic capabilities for such support. This can be accomplished, among other things, through the USSF’s Joint Commercial Operations cell, Commercial Space Office, and Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve, as well as the NRO’s Commercial Systems Program Office.

Furthermore, the DoD and intelligence community should engage US space system manufacturers, owners, and operators to influence the design, development, and operations of commercial space systems. They should also incorporate and specify protection requirements in competitions for procurements of commercial goods and services. Additionally, federal authorities (resident in the Departments of Commerce, Transportation, State, Homeland Security, and Justice as well as the Federal Communications Commission) and relationships with the private sector should be utilized to establish a consistent regulatory approach to mandate and enforce minimum levels of protection for commercial space systems to help safeguard US national and economic security.

Where the DoD or intelligence community determines it is prudent to employ commercial capabilities for national security space missions, they should selectively supply government furnished equipment for threat awareness, protection, or defense to the commercial vendors. Similarly, they should selectively fund commercial space enterprises to modify their systems for enhanced threat awareness, protection, or defense.

Finally, the federal government should assess the utility and feasibility of enabling legislation for indemnification, anchor tenancy, and advanced funding in exchange for the ability to leverage commercial space capabilities for national security. The precedent of legislation for indemnification of commercial asserts for such purposes was established in the cases of both the merchant marine and civil reserve aircraft fleets.[38]

References

- Department of Commerce, “U.S. Space Economy Statistics 2012-2021”.

- Bryce Technologies, Start-Up Space: Update on Investment in Commercial Space Ventures 2023./li>

- “National Space Policy of the United States of America,” The White House, December 9, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Space Policy Directive 2, Streamlining Regulations on Commercial Use of Space, May 24, 2018.

- See, for example, Marc J. Berkowitz, “Leveraging Commercial Space Capabilities for U.S. National Security,” National Security Space Association, February 22, 2022.

- U.S. Space Force Commercial Space Strategy (Washington, D.C.: Headquarters U.S. Space Force, April 8, 2024).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Dr. Troy Meink, NRO Principal Deputy Director, “Space Symposium Remarks,” April 9, 2024, 3d; and Dr. Christopher J. Scolese, Director, National Reconnaissance Office, “Testimony to House Armed Services Committee, Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, Hearing on Fiscal Year 2024 National Security Space Programs,” April 26, 2023.

- Sandra Erwin, “National Reconnaissance Office embracing mix of big and small satellites”, SpaceNews, March 18, 2024.

- Joint Publication 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, D.C.: The Joint Staff, April 2001 as amended through 2010), p. 375.

- See for example, William J. Clinton, A National Security Strategy for a New Century (Washington, D.C.: The White House, December 1999), p.12; and United States Space Priorities Framework (Washington, D.C.: The White House, December 2021), p.1.

- “National Space Policy of the United States of America.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Department of Defense Directive 3100.10, “Space Policy,” August 30, 2022.

- Commercial Space Integration Strategy, (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2024).

- “Tri-Seal Commercial Space Protection Framework,” National Reconnaissance Office, August 31, 2023.

- Josh Rogin, “A Shadow War in Space is Heating Up Fast,” The Washington Post, November 30, 2021.

- Defense Intelligence Agency, Challenges to Security in Space (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2022), pp. 17-18, 27-29.

- “Press Briefing by Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre and White House National Security Communications Advisor John Kirby,” The White House, February 15, 2024.

- Challenges to Security in Space, (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2022), pp. 30-32.

- See, for example, Marc J. Berkowitz, “Strategic Lessons for the Russia-Ukraine Conflict,” in David J. Trachtenberg, ed., Lessons Learned from Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine National Institute for Public Policy Occasional Paper, (Vol. 3, No. 10 (October 2023), pp. 11-20.

- “Russian Direct-Ascent Anti-Satellite Missile Test Creates Significant, Long-Lasting Space Debris,” U.S. Space Command Office of Public Affairs, November 15, 2021.

- “Russian ASAT Test Debris Visualization,” UK Space Agency, November 11, 2021.

- United Kingdom National Cyber Security Centre, “Russia Behind Cyber Attack with Europe-Wide Impact an Hour Before Ukraine Invasion”, May 10, 2022.

- “KA-SAT Network Cyber Attack Overview,” Viasat Corporate News, March 30, 2022.

- Alex Horton, “Russia Tests Secret Weapon to Target SpaceX’s Starlink in Ukraine,” The Washington Post, April 18, 2023.

- Juliana Suess, “Jamming and Cyber Attacks: How Space is Being Targeted in Ukraine,” Royal United Services Institute, April 5, 2022; and Georgi A. Angelov, “Suspected Russian GPS Jamming Risks Fresh Dangers in Black Sea Region”, Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty, October 26, 2023.

- “OSCE Spots Russia's Brand New Military Equipment in Occupied Donbas,” UNIAN, April 3, 2019.

- Konstantin Voronstov, “Statement at the Thematic Discussion on Outer Space (Disarmament Aspects) in the First Committee of the 77th Session of the UN General Assembly,” October 26, 2022.

- Guy Faulconbridge and Dmitry Antonov, “Russia responds icily to U.S. hint on arms control talks with Moscow and Beijing”, Reuters, March 30, 2024.

- See, for example, Marc J. Berkowitz, “Dominance or Deterrence: The Role of Military Power in Addressing Challenges to U.S. National Security,” Comparative Strategy, (October 17, 2022)

- Ibid.

- See, for example, U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment, Anti-Satellite Weapons, Countermeasures, and Arms Control (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1985).

- See, for example, James D. Rendelman and Robert E. Ryals, “Private Defense of Space Systems and Letters of Marque and Reprisal,” AIAA Space 2015, August 28, 2015/

- 46 U.S. Code, Merchant Marine Act, 1920; and 10 U.S. Code, Civil Reserve Air Fleet

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.