The satellite eavesdropping stations of Russia’s intelligence services (part 1)by Bart Hendrickx

|

| Some ground stations have been targets of Ukrainian drone attacks in recent months, a clear sign that they are believed to play a considerable role in Russia’s intelligence collection efforts. |

The researchers soon realized that two questions would have to be addressed before a decision was made to intercept an enemy satellite. The first was to determine the purpose of the satellite, in order to assess whether it was worth attacking, and the second to accurately calculate its orbital parameters in order to ensure a successful intercept. The latter task could largely be accomplished with ground-based optical and radar systems. While the satellite’s orbit would also provide important clues about its purpose, the researchers concluded that additional information on its mission could be gleaned from intercepting the signals that it downlinked to the ground. They estimated that this would increase the chances of positively identifying its purpose by 20 to 30%. It would also allow to determine if space objects flying over Russian territory were active satellites or merely space junk.

In early 1963, representatives of the 4th Directorate first approached officials of both the KGB and GRU to discuss the wisdom and feasibility of creating a ground-based network of stations to eavesdrop on foreign satellites. They had good reason to raise this matter with the country’s intelligence agencies since both already had departments specializing in signals intelligence (SIGINT). The KGB (Committee for State Security), which was subordinate to the USSR Council of Ministers (the Soviet government), was responsible for both internal security and foreign intelligence, performing functions similar to those of the FBI and CIA in the United States. The GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate) was and still is the foreign military intelligence agency of the Armed Forces’ General Staff and the equivalent of the US Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), although their functions do not entirely overlap. The departments within the KGB and GRU responsible for SIGINT were the 16th Directorate and the 6th Directorate respectively. The GRU was also entrusted with processing data obtained by Soviet photoreconnaissance and electronic intelligence satellites.

Although the idea of setting up a foreign satellite SIGINT network was presented to both the KGB and GRU, there seems to have been more support for it in the ranks of the GRU. This was most likely because the potential ASAT targets it would help identify would primarily be military satellites. A vital role in its ultimate approval is said to have been played by Mikhail I. Rogatkin, the deputy commander of the GRU’s 6th Directorate. The official go-ahead for the Zvezda network came in the form of a Communist Party and government decree. According to one Russian social media site, the decree (nr. 509-194) was signed on June 30, 1965. This makes sense, because another Party decree (nr. 507-192) issued on the same day is known to have given the go-ahead for developing the country’s ground-based space surveillance system, abbreviated in Russian as SKKP.

The fact that there were separate decrees on Zvezda and SKKP underlines that they were independent networks run by different organizations. SKKP was a network of radar and optical systems to provide tracking and other data on satellites and fell under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Defense’s 4th Directorate. Zvezda, the SIGINT system, was in the hands of the GRU. Still, there may have been at least some interaction between the two networks. For instance, Zvezda may well have relied on trajectory measurements from SKKP to keep track of target satellites. Identification of potential ASAT targets does seem to have become much less of a priority for Zvezda at an early stage, with the focus soon shifting to communications intelligence, that is the interception of voice communications relayed by satellite (more on that in part 2 of this article).

Although it looks like Zvezda was approved in 1965, it would appear that actual work on the network began in 1966. This can be deduced from several pins and pennants issued to mark anniversaries of the system. Many of them show what appears to be the official emblem of Zvezda with a big star in the center and two smaller stars in the upper left and right, possibly symbolizing two orbiting satellites.

Pin commemorating Zvezda’s 50th anniversary in 2016. Source: Russian collector site. |

According to one source, the initial goal of Zvezda was to construct three SIGINT sites, which would relay the collected information to a data processing center in the Moscow area. Known as Military Unit 51428, it was built in a place called Zagoryanskiy in the Shcholkovo region in the northeastern outskirts of the capital. It was reportedly officially established on April 15, 1966, which may be considered the formal birth date of the Zvezda network. It served as the headquarters of Zvezda and its commander was in overall charge of the network. Zvezda was initially led by Yevgeniy G. Kolokolov, who was replaced in 1974 by Stepan I. Ternovoi.

| In order to be able to intercept signals from foreign satellites, the Zvezda sites had to be located on the periphery of the Soviet Union’s territory. |

Eventually, the Zvezda network would grow to consist of 11 sites on Soviet territory. The first tier was declared operational in 1972 and the second (called Zvezda-A) in 1978. Some of the parabolic antennas for Zvezda were placed at existing GRU sites equipped with a radio direction finding system called Krug (“circle”). These were large circular antenna arrays (sometimes called wullenwebers after their German World War Two progenitor) that had been used by the GRU since the early 1950s to pinpoint the position of NATO strategic bombers and reconnaissance aircraft through the method of triangulation. The sites also had other names apart from their Military Unit numbers. At least some were called “Independent Centers for Radio Reconnaissance of Space Objects” (OPRRKO), preceded by a specific number.

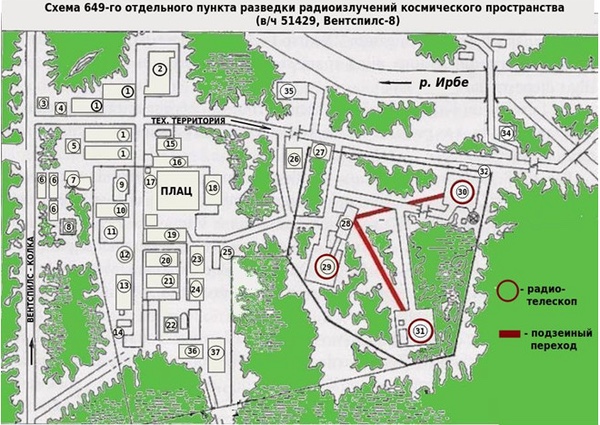

In order to be able to intercept signals from foreign satellites, the Zvezda sites had to be located on the periphery of the Soviet Union’s territory. The first priority was to build a site close to the country’s western border. Three locations were considered, namely the region of Kaliningrad (the Russian exclave between Lithuania and Poland) and the areas of Mukachevo in Ukraine and Ventspils in Latvia, both republics of the Soviet Union at the time. The choice fell on Ventspils, where construction work got underway not long after the approval of Zvezda. This was a major construction effort. The site (designated Military Unit 51429) had to be built from scratch in a remote location some 20 kilometers northeast of Ventspils and was to house three big dish antennas, various technical support facilities as well as a residential area. It seems to have reached some limited operational capability before the end of the 1960s.

Map of the Zvezda station near Ventspils, Latvia. The residential area is on the left and the operations zone on the right. It had three parabolic antennas with diameters of 8 meters (nr. 29), 32 meters (nr. 30) and 16 meters (nr. 31). The latter two were connected via tunnels with a technical building (nr. 28). Source |

There is conflicting information on exactly when the other sites were incorporated into the system. Four more were built in the western part of the country, more specifically in the vicinity of Moscow and Odessa (Ukraine) as well as in Georgia and Azerbaijan. The site near Odessa seems to have been replaced in the late 1980s by another one in the same area that also had a Krug system.

Zvezda station in Chabanka near Odessa with a 12-meter parabolic antenna. Source |

Deeper inland, close to the country’s southern border, there was a station in Maksimovshchina near Irkutsk in Siberia. Finally, there were two sites in the country’s Far East, one near Yakovlevka and another in Chukotka.

According to various sources, elements of the Zvezda system were also deployed outside the Soviet Union in friendly Communist nations. This made it possible to expand the range of target satellites. The biggest Soviet SIGINT base abroad was in Cuba near Torrens and for some reason was referred to by the CIA as Lourdes. From later revelations it turned out that the site was operated jointly by the GRU, the KGB, and the Soviet Navy, although the GRU seems to have been the prime user. The GRU signals intelligence team (called “Trostnik”) arrived first in late 1963 and was followed later in the 1960s by the Navy team (“Platan”) and in the 1970s by the KGB team (“Orbita”). The Lourdes site was capable of monitoring a wide array of commercial and government communications in the southeastern United States and between the United States and Europe. This included intercepting microwave and shortwave transmissions and picking up telemetry from rockets launched from Cape Canaveral. Gathering foreign satellite intelligence was only one of its tasks. Both the GRU and KGB were involved in this, but the details are sketchy. Some Lourdes veterans claim that the GRU’s satellite SIGINT division in Cuba was not formally incorporated into the Zvezda network until 1993 under the name “10th Radio Electronic Center” (10 RETs).

Other Zvezda units were reportedly located in Vietnam, Mongolia, and Burma (Myanmar). The one in Vietnam was in Cam Ranh Bay, which was home to a major US military base during the Vietnam War until it was captured by North Vietnamese forces in 1975. In 1979 it was leased to the Soviet Union for use as a naval and SIGINT base. The Zvezda unit in Mongolia was part of a larger Soviet intelligence team sent to the country in the late 1960s under the name “Expedition Horizon”. Nothing more is known about the Zvezda unit in Burma, except that it was situated in the capital Rangoon (now Yangon). All these facilities were probably also engaged in other types of SIGINT collection, with the main focus being on China. [1]

| Most of the Zvezda sites on the Russian mainland remain operational today. How many exactly there are is a closely guarded secret. |

It is not clear if the CIA had a complete picture of the GRU’s satellite eavesdropping network on Soviet territory. Declassified documents mention only the stations near Ventspils (referred to there as the “Vicak Space Tracking Facility”), Yakovlevka (called “Andreyevka satellite communications station”), Maksimovshchina (“Kuda RADCOM receiver station”) and Akstafa in Azerbaijan. None of these were specifically linked to the GRU and only the ones near Ventspils and Yakovlevka were recognized as being used for communications satellite intelligence. This was because some of the parabolic antennas seen there were identical to those observed at the site in Lourdes, Cuba. It should be noted though that the documents declassified to date may provide only limited insight into the CIA’s true understanding of the Zvezda network. [2]

Post-Soviet era

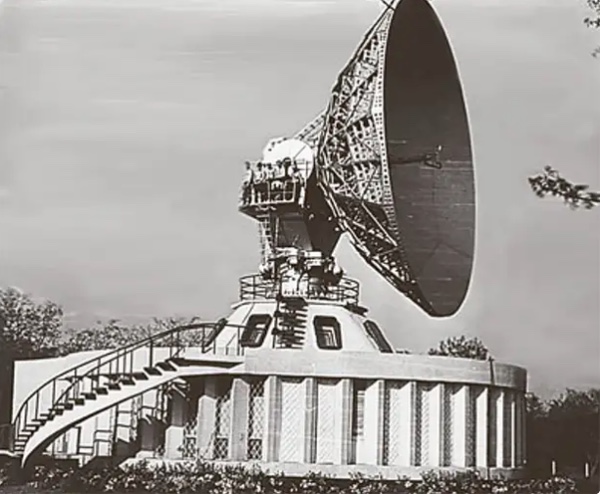

The disintegration of the USSR in late 1991 led to the closure of the Zvezda facilities that were located in the former Soviet republics of Latvia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. Latvian sources claim that Russian troops deliberately disabled much of the hardware at the site near Ventspils before definitively pulling out of Latvia in 1994. However, the two antennas that remained (the 16-meter and 32-meter ones) were refurbished for astronomical observations and became the core of the Ventspils International Radio Astronomy Center (VIRAC). The 16-meter dish antenna was replaced by a new one last decade. The nearby residential area, called Irbene, is now abandoned and has become a popular destination for urban explorers.

VIRAC’s 32-meter radio telescope (RT-32), originally part of the GRU’s Zvezda network. Source: Wikipedia |

The Zvezda facility in Velikiy Dalnik near Odessa in Ukraine fell in the hands of the Ukrainian army and became known as Military Unit A2571 and the 96th Satellite Radio Intelligence Center. In late 2017, the Ukrainian government allocated money to turn the facility over to the country’s intelligence services, but it is unclear if this actually happened. A Russian strike on the site was reported in March 2022, shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Its current status is unknown.

Most of the Zvezda sites on the Russian mainland remain operational today. How many exactly there are is a closely guarded secret. One way of identifying them is by looking for pennants of military units belonging to the network. These occasionally appear on Russian collector forums and can be recognized by the telltale emblem of the Zvezda network (one big star in the center and two smaller stars on top). Their locations can be determined via a variety of online sources and Google Earth imagery, which also provides some clues about their current status. Unmistakable signs of ongoing activity are changing antenna orientations, the appearance of new antennas and the presence of vehicles in nearby car parks.

Pennants of military units belonging to the Zvezda network. One is dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the GRU. Source: Russian collector forum. |

A total of nine units can be positively identified as belonging to Zvezda, four of which had their origins in the Soviet days. The network’s headquarters (Military Unit 51428) is still in Zagoryanskiy in Moscow’s Shcholkovo region. It is currently headed by Yevgeniy A. Nesterov, who presumably also acts as commander of the entire Zvezda network. Satellite imagery of the site shows only administrative buildings and a few small dish antennas, meaning that it is probably used only for collection and analysis of data gathered by the other sites.

Other Soviet-era sites that are clearly still active are near Yakovlevka in the Far East and Irkutsk in Siberia. In the middle of last decade, there were plans to expand the role of the site near Yakovlevka by building an optical observatory that was to become part of a military space surveillance system called Pritsel. However, there are no signs of it in the most recent Google Earth imagery from November 2022. [3]

There is some uncertainty about the status of the Zvezda site in Shcholkovo (Military Unit 63553), located some four kilometers east of the network’s headquarters, right next to a major space tracking center known as OKIK 14. There are some indications from online sources that the unit may have been disbanded, but a few new smaller dish antennas have shown up at this location in recent years next to the 16-meter antenna that has been around since the Soviet days. A Zvezda unit that was formed near Beringovskiy in Chukotka in 1984 was closed down in 2001 and replaced the following year by a new one about 200 kilometers to the north in Tavaivaam near the city of Anadyr.

16-meter antenna at Zvezda unit 63553 in Shcholkovo. Source: Russian social media. |

The loss of a number of Zvezda units in former Soviet republics was compensated by the creation of new ones within several hundred kilometers on Russian territory. As can be learned from a picture posted on a Russian social media site, a decision was made in 1994 to transfer at least some of the personnel of the former Zvezda site in Ventspils, Latvia, to an already existing GRU facility in Toivorovo (nr. 41480) in the St.-Petersburg region. This already had a Krug radio direction finding system and was now gradually expanded with parabolic antennas for the Zvezda network.

A new unit (25137) was set up even closer to Latvia in the city of Kaliningrad. Based on Google Earth imagery, it was built sometime between 2003 and 2007. Whereas all the others are in relatively remote locations, this one, remarkably enough, is in the middle of a residential area. In April 2022, Ukraine’s military intelligence service published a list of employees of the unit, claiming they had been involved in war crimes in Ukraine. It is unclear what kind of combat role they could have had there. [4]

Zvezda unit 25137 in the city of Kaliningrad. Source: Google Street View |

Another new Zvezda facility (nr. 33443) was constructed near Mikhailovsk in the Stavropol region in southwestern Russia, about 500 kilometers north of the abandoned site in Azerbaijan (nr. 12151). It is visible in the earliest available Google Earth imagery from 2002. Evidence that it serves as a replacement for station 12151 comes from the fact that both unit numbers are seen on some pennants and pins.

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 allowed Russia to build a new Zvezda facility (nr. 65372) in the area of Sevastopol, which is just over 300 kilometers south of the unit near Odessa that fell in the hands of Ukraine after the collapse of the USSR. Both the new Zvezda units (33443 and 63572) were targets of Ukrainian drone attacks in July 2024. [5]

| Meanwhile, there are some indications that Russia may be planning to revive its SIGINT activities in Cuba. |

At least two of the Zvezda units stationed abroad (the ones in Cuba and Vietnam) continued to operate for another decade until the then newly elected President Vladimir Putin decided to close them down in 2001. As can be learned from a handful of online sources, the Cuban GRU unit (or at least part of it) was re-located to Klimovsk about 50 kilometers south of Moscow to form the new Military Unit 47747. It became part of an already existing GRU site in Klimovsk called Military Unit 34608, also informally known as Gudok (“horn”, “whistle”). This has existed since the Soviet days. A history of the GRU published in 1999 identified it as a center that collected and processed data from the GRU’s SIGINT stations on Soviet territory and abroad and claimed that a similar role was performed by a facility in Vatutinki near Moscow. [6] If that is true, the division of labor between them and the Zvezda headquarters in Zagoryanskiy is not entirely clear. Possibly, Klimovsk and Vatutinki were (and still are) nerve centers for the GRU’s overall SIGINT collection effort and Zagoryanskiy focuses solely on satellite-related SIGINT.

The Cuban roots of Military Unit 47747 are evident from this pennant showing both the Russian and Cuban flags. Source: forum of Lourdes veterans. |

Satellite imagery shows the appearance of numerous parabolic antennas at the site in Klimovsk after 2005, some of which may have been transferred from Cuba. Military Unit 47747 was formally disbanded in 2013, but it looks like that was no more than a bureaucratic move. Judging from satellite images, the antenna field in Klimovsk (referred to by some sources as “Zone 5”) continues to be active to the present day. While there is no evidence that it is part of Zvezda, it is hard to imagine it is not. Military Unit 34608 was attacked by Ukrainian drones in August 2024. It is not known if Zone 5 was the target of the attack and, if so, whether it was damaged. This GRU unit is spread over a significant area and also includes two other zones, one with Krug direction finding antennas and another with unidentified antennas that may be related to tropospheric or ionospheric communication. [7]

Meanwhile, there are some indications that Russia may be planning to revive its SIGINT activities in Cuba. A recent investigation by The Insider shows that GRU employees disguised as diplomats (including veterans of Military Unit 47747) have been deployed to the island, possibly to take part in that work. [8] However, no evidence has been presented so far that actual hardware is already being constructed. Recent research has also uncovered the presence of Chinese SIGINT facilities in Cuba and it has been speculated that China and Russia may share signals intelligence data.

Table 1: GRU satellite eavesdropping stations on Soviet/Russian territory.

| MILITARY UNIT NR. | OTHER NAME(S)* | LOCATION** | NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51428 | 99 GTsSS | Zagoryanskiy (Moscow region) | Network headquarters. No major antennas. |

| 63553 | 407 OPRRKO | Shcholkovo (Moscow region) | Probably active. |

| 34608 (47747) | 10 RETs | Klimovsk (Moscow region) | Active. Not confirmed as being part of Zvezda. Co-located with Krug system. Attacked by Ukraine in August 2024. |

| 51870 | 1580 OPRRKO | Maksimovshchina (CIA: Kuda) (Irkutsk region) | Active. Co-located with Krug system. |

| 51430 | 649 OPRRKO | Yakovlevka (CIA: Andreyevka) (Far East) | Active. |

| 41480 | 876 ORPUS | Toivorovo (St.-Petersburg region) | Active. Co-located with Krug system. |

| 25137 | 1237 TsS RER | Kaliningrad | Active. Set up between 2003 and 2007. |

| 33443 | Moskovskoye (Stavropol region) | Active. Replaced Military Unit 12151. Attacked by Ukraine in July 2024. | |

| 65372 | Sevastopol (Crimea) | Active. Set up in 2015. Attacked by Ukraine in July 2024. | |

| 90099 | Tavaivaam (Chukotka) | Active. Replaced Military Unit 51595 in 2002. Co-located with unfinished Krug system. | |

| 51595 | 902 ORPU | Beringovskiy (Chukotka) | Inactive. Shut down in 2001. Co-located with Krug system. |

| 51429 | 649 OPRRKO | Ventspils (CIA: Vicak) (Latvia) | Inactive. Two antennas now used for radio astronomy. |

| 48657 | 539 OPRRKO | Chabanka (Odessa region/Ukraine) | Inactive. Presumably shut down in the late 1980s and replaced by Military Unit 42028. |

| 42028/A-2571 | 449 OPRRKO/96 OTsRRKO | Velikiy Dalnik (Odessa region/Ukraine) | Owned by Ukraine. Co-located with Krug system. Attacked by Russia in March 2022. Status unknown. |

| 12151 | Agstafa (Azerbaijan) | Inactive. Replaced by Military Unit 33443. | |

| 51868 | Gardabani (Georgia) | Inactive. Co-located with Krug system. |

*Some of these names may no longer be in use

**The hyperlinked place names lead to the most recent Google Earth imagery of the sites. The place names are those usually given by Russian sources or those of the most nearby places in Google Earth imagery. Alternative place names given in CIA documents are added.

The KGB/FSB network

Soviet era

As explained earlier, the KGB had been involved in the discussions leading up to the creation of the GRU’s Zvezda network in the mid-1960s. Although Zvezda became the responsibility of the GRU, the KGB seems to have played at least some kind of role in the project. For instance, there was a KGB division at the Zvezda site near Ventspils in Latvia which had a different number (93364) than its GRU neighbor (51429). There are also some indications that the KGB had a division at the big GRU SIGINT site near Yakovlevka in Russia’s Far East and, as mentioned before, GRU and KGB teams were co-deployed at the SIGINT site in Lourdes, Cuba.

However, the KGB’s 16th Directorate (responsible for SIGINT) eventually also established its own dedicated network of satellite listening stations. It is not known if the network was officially created at a specific moment or even if it has an overall name. The satellite interception hardware was installed at already existing KGB sites that were equipped with conventional antennas for picking up high-frequency (HF) radio transmissions. As the emphasis shifted to foreign satellite intelligence in the 1970s and 1980s, many of the HF antennas were gradually replaced by parabolic dish antennas.

The existence of the Soviet-era KGB network came to light in 2012 with the declassification of a 1983 CIA report titled “KGB COMINT Collection Sites”. [9] The stations were spread across Soviet territory in much the same way as those of the GRU’s Zvezda network. The headquarters were situated near Chekhov, some 70 kilometers south of Moscow. Unlike the headquarters of the Zvezda system, this was also engaged in intelligence collection itself. A handful of sources refer to it as the Central Special Service Radio Node (TsRUSS), whereas the other sites belonging to the network were called Independent Special Service Radio Nodes (ORUSS). Another name seen for them is Special Communications Center (TsSS). Even though the KGB was not a military organization, all the stations were also assigned Military Unit numbers in a possible attempt to cover up their real owner.

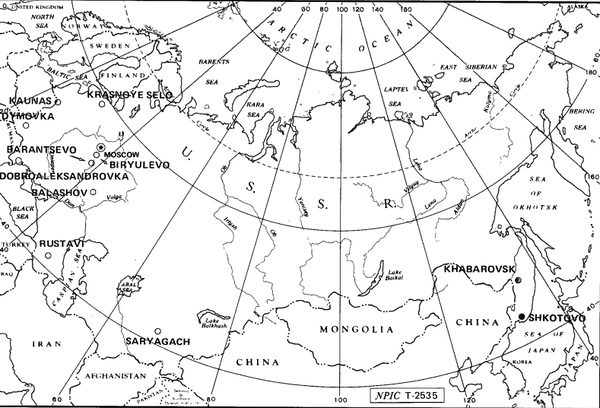

There were eight stations in the western part of the country: two in the Moscow area (including the headquarters), one near Leningrad, one in Lithuania, one near Saratov, one in Georgia and two in Ukraine (some sources mention a third one in Balaklava in Crimea, but there is no further information on this). Further inland, close to the southern border, there was a station in Kazakhstan, just a few kilometers from the border with Uzbekistan. Two more stations were in the Far East of the USSR near Khabarovsk and Vladivostok.

CIA map showing the location of Soviet-era KGB satellite eavesdropping stations. Source |

Post-Soviet era

After the break-up of the Soviet Union, the KGB split up into several smaller entities. The 16th Main Directorate, responsible for SIGINT, was absorbed by a new organization called the Federal Agency of Government Communications and Information (FAPSI), more or less the equivalent of the US National Security Agency. Within FAPSI, the 16th Main Directorate was reorganized as the 3rd Main Directorate, also known as the Main Directorate for Radio-Electronic Intelligence of Communications Systems (GURRS). After the dissolution of FAPSI in 2003, the 3rd Main Directorate (or at least part of it) was transferred to the Federal Security Service (FSB), the domestic security and counterintelligence agency that had evolved from the KGB’s internal security departments. There it became known as the 16th Center, also called the Center for Radio-Electronic Intelligence by Means of Communication (TsRRSS) and Military Unit 71330. Aside from its SIGINT activities, the 16th Center also seems to have taken on an important role in cyberwarfare. It has been in the news several times in recent years because of its alleged involvement in cyber operations against critical infrastructure in various countries.

| The existence of the Soviet-era KGB network came to light in 2012 with the declassification of a 1983 CIA report titled “KGB COMINT Collection Sites”. |

In the wake of the USSR’s collapse, FAPSI had to abandon the stations located in former Soviet republics, but the ones situated within the boundaries of the Russian Federation (six in all) remained active. This was not realized until 2013, when National Security Agency veteran and SIGINT historian Matthew Aid used the declassified CIA report on the Soviet-era KGB stations to analyze their status with the help of satellite imagery. [10] It has since become possible to learn more about the fate of the abandoned stations and also to identify several new ones that have been built to compensate for their loss.

The site in Georgia (nr. 61615) was closed down, but its personnel were moved to a new SIGINT site (nr. 11380) in Dubovyy Rynok in the Krasnodar region about 400 kilometers from the border with Georgia. Another station belonging to the FSB’s 16th Center (nr. 03110) is right next to the Georgian border in Vesyoloye. It has several antennas covered by radomes, but it is not clear if these are used to eavesdrop on satellites. [11]

New FSB COMINT collection site in Dubovyy Rynok in the Krasnodar region in southwestern Russia. Source: Google Earth. |

The station in in Kazakhstan (nr. 83521) remained in the hands of FAPSI until it was turned over to the Kazakh authorities in 1998. It was renamed Military Unit 2020 and placed under the authority of the Border Service of Kazakhstan’s National Security Committee, the country’s intelligence agency. Judging from Google Earth images, it is still active. Most of the Russian personnel was transferred to a new site in Verbnoye in the Kaliningrad region which retained the unit number of the former Kazakh station. It is just about 200 kilometers west of the former KGB station in Linksmakalnis in Lithuania, which was closed down after the breakup of the Soviet Union, and has presumably taken over at least part of its functions. Additional coverage of the Baltic region is provided by another new station (Military Unit 49911) near Georgiyevskaya in the Pskov region, just a few kilometers from the border with Estonia.

FSB site nr. 49911 in the Pskov region. Source |

The two Soviet-era sites in Ukraine, situated in Dobroaleksandrovka in the Odessa region and near Lypikva in the Lviv region, became the property of Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU), which turned them over to the country’s newly formed Foreign Intelligence Service (SZRU) in 2004. In late 2020, a tender was published for repair work at the station near Dobroaleksandrovka (known as Ovidiopol-2), which was interpreted by some Russian media at the time as a sign that it was to be transferred to NATO not only for signals intelligence but also for electronic jamming of Russian satellites. According to Russian media reports, the site was “totally destroyed” in a Russian attack in March 2024, a claim that it is impossible to verify in the absence of recent satellite imagery. The status of the other Ukrainian SIGINT site near Lypivka is unknown. There have so far been no reports of any Russian attacks at this location.

Russia, in turn, regained control of a facility near Alushta in Crimea featuring a 25-meter dish antenna and two smaller ones. According to some sources, the site was established in the late 1960s for space tracking. After the collapse of the USSR, it was taken over by Ukraine’s intelligence services and apparently repurposed for SIGINT, although it is unknown how much work was actually done with it. Following the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the site was renamed Military Unit 28735 and became the property of the FSB, which most likely uses it for foreign satellite intelligence. The station was reported to be the scene of Ukrainian drone and missile attacks in December 2023 and May 2024 and it is not known to what extent it has been damaged.

FSB Military Unit 28735 on the shores of the Black Sea. Source |

Table 2: KGB/FSB satellite eavesdropping stations.

| MILITARY UNIT NR. | OTHER NAME(S)* | LOCATION** | NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51952 | TsRUSS/17 TsSS | Nerastannoye (CIA: Barantsevo) (Moscow region) | Network headquarters. Active. |

| 61608 | 1 ORUSS/20 TsSS | Tsaritsyno (CIA: Biryulevo) (Moscow region) | Active. |

| 61240 | 4 ORUSS/23 TsSS | Mikhailovka (CIA: Krasnoye Selo) (St.-Petersburg region) | Active. |

| 44231 | 19 TsSS | Voskhod (CIA: Balashov) (Saratov region) | Active. |

| 83417 | 25 TsSS | Shkotovo (Vladivostok region) | Active. |

| 70822 | 18 TsSS | Vostochnoye (CIA: Khabarovsk) (Khabarovsk region) | Active. |

| 83521 | 21 TsSS | Verbnoye (Kaliningrad region) | Active. Transferred from Kazakhstan. |

| 49911 | 22 TsSS | Georgiyevskaya (Pskov region) | Active. |

| 11380 | - | Dubovyy Rynok (Krasnodar region) | Active. Replaced Military Unit 61615. |

| E6362/K1401/28735 | - | Alushta (Crimea) | Active. Taken over from Ukraine. Attacked by Ukraine in December 2023 and May 2024. |

| 71272 | 6 ORUSS | Linksmakalnis (CIA: Kaunas) (Lithuania) | Inactive. |

| 83525/E6398/K1412 | Lypivka (CIA: Dymovka) (Lviv region, Ukraine) | Status unknown. Owned by Ukraine. | |

| 21489/E6282/K1415 | 8 ORUSS | Dobroaleksandrovka (Odessa region/Ukraine) | Active. Owned by Ukraine. Attacked by Russia in March 2024. |

| 83521/2020 | 10 ORUSS | Saryagash (Kazakhstan) | Active. Owned by Kazakhstan. Russian personnel moved to Verbnoye, Kaliningrad region. |

| 61615 | Gardabani (CIA: Rustavi) (Georgia) | Inactive. Replaced by Military Unit 11380. |

*Some of these names may no longer be in use

**The hyperlinked place names lead to the most recent Google Earth imagery of the sites. The place names are those usually given by Russian sources or those of the most nearby places in Google Earth imagery. Alternative place names given in CIA documents are added.

References

- Among the sources used for the Soviet-era history of Zvezda are: Memoirs of Aleksandr Gorelik in a history of the 45 SNII research institute, 2005 ; History of the GRU’s SIGINT activities by Mikhail Boltunov, 2011, p. 156-160 ; Memoirs of GRU veteran Oleg Krivopalov, 2011. Krivopalov served at Zvezda unit nr. 51430 near Yakovlevka in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In 2017 he published a book entirely dedicated to the history of this Zvezda unit, but this is not available online. Bibliographical details are here.

- CIA documents related to the GRU stations were published in October 1977 (Similarity between electronics facilities at Lourdes, Cuba, and Vicak, USSR), August 1980 (Lourdes central Sigint complex) and March 1982 (Activity at selected Soviet space tracking facilities).

- Tender documentation published in July 2016. More on Pritsel in this thread on the NASA Spaceflight Forum (see Replies 2 and 10).

- List published by Ukraine’s military intelligence service in April 2022.

- S. Syngaivska, Over 450 km behind lines: Ukraine targets secret Russian base with the Zvezda space reconnaissance system, Defense Express, July 4, 2024.

- History of the GRU by A. Kolpakidi and D. Prokhorov, 1999, p. 44.

- Mysterious Gudok: what is the strategic intelligence center attacked by Ukraine near Moscow, Defense Express, August 22, 2024.

- S. Kanev, Our men in Havana: arrival of GRU specialists in Cuba points to Russia reviving its base for spying on the US, The Insider, June 27, 2023.

- KGB COMINT collection stations, USSR, CIA report published in October 1983.

- Blogpost by Matthew Aid, July 2, 2013.

- The latest Google Earth imagery of the FSB SIGINT site 03110 in Vesyoloye is here. The fact that it is subordinate to the FSB’s 16th Center (Military Unit 71330) can be determined from court documentation published in 2017.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.