Review: Sallyby Jeff Foust

|

| “We didn’t plan to hide anything,” O’Shaughnessy recalls in the film. “It hurt me, but I’m not sure it hurt Sally.” |

But, some time last week, the article disappeared from the NASA website: it was there on January 25, according to The Internet Archive, but gone by January 29. The deletion could be for any number of reasons: a site update gone awry, for example. (Other NASA articles about shuttle program history don’t seem affected.) The timing of it, though, suggested to some that it was linked to executive orders by the Trump Administration targeting diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, perhaps since the article made a passing reference to diversity at the very end. “As a legacy of the diversity represented in the astronaut Class of 1978, during the Artemis program, NASA will land the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon.”

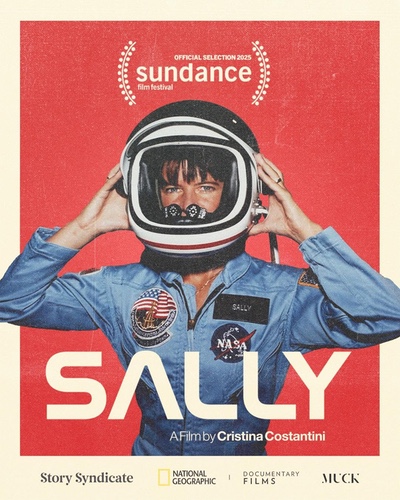

That came to mind while watching a new documentary about the most famous member of that 1978 class. Sally, which premiered last week at the Sundance Film Festival (including online screenings), is a movie about the life of Sally Ride, the first American woman in space. It is also a tale about her relationship with Tam O’Shaughnessy, the woman who was Ride’s life partner for years, a relationship hidden from the public until Ride’s death in 2012.

Director Cristina Costantini generally follows a chronological approach to Ride’s life, moving quickly into the astronaut selection process, the media whirlwind that enveloped Ride and the other women selected in that class, training, and Ride’s flight on STS-7. Interweaved with that is Ride’s links to O’Shaughnessy: the two met as tweens at a tennis event and rekindled the friendship as adults, which only later became romantic. The latter part of the film, after Ride leaves NASA, is devoted more closely to that relationship as they work together publicly through efforts like the Sally Ride Science educational projects while privately becoming partners.

Many of the details about Ride’s professional life in the film are not new, although there are some interesting anecdotes on the margins, such as about Ride’s competitiveness. Sullivan described an incident where she was training to use the shuttle’s robotic arm when she noticed Ride moving behind her, going to the deck below in the simulator. Moments later, the arm stops moving. Sullivan, investigating the problem, found circuit breakers pulled from a panel that Ride had just passed by. “Was Sally just helpfully playing instructor and seeing if I could figure it out,” she said, “or just messing with my head?”

The core of the film, though, is Ride’s relationship with O’Shaughnessy and how that evolved over the years. O’Shaughnessy is interviewed extensively, sharing photos and letters from Ride. A central question the movie grapples with is why Ride wanted to keep her relationship with O’Shaughnessy private, even up to the end of her life. “We didn’t plan to hide anything,” O’Shaughnessy recalls in the film. “It hurt me, but I’m not sure it hurt Sally.”

| Costantini described the reenactments as a way to “recreate this love story” with imagery that didn’t exist, going so far as to shoot the scenes on film to give them a more historical feel. |

One reason, the film speculates, is that Ride did not grow up in a family that shared their feelings much. But there was also a fear that Ride could lose her chance to go to space, and all the public praise she received, if she was more open, citing the experience of tennis star Billie Jean King when she was outed in that era. (King, interviewed in the film, said it was “downhill for a lot of years” for her after that. “It must have served as a warning.”)

Sally makes extensive use of archival footage and previously recorded interviews with Ride, along with interviews of O’Shaughnessy, former astronauts like Sullivan, Anna Fisher, Mike Mullane, and Steve Hawley, who was briefly married to Ride. Her sister, Bear, and mother are also interviewed.

One interesting, if somewhat jarring, technique, is the use of reenactments of meetings between Ride and O’Shaughnessy over the years, from their initial encounter at a tennis event to Ride’s deathbed. There is no dialogue associated with these reenactments, and sometimes the viewer seems like they are an interloper eavesdropping on private, intimate events. In an interview after a screening of the movie, Costantini described the reenactments as a way to “recreate this love story” with imagery that didn’t exist, going so far as to shoot the scenes on film to give them a more historical feel.

“It bought back some great, great, unbelievable memories,” O’Shaughnessy added. “I think it added to the film because, otherwise, you can’t get a picture for what it was like.”

The film is backed by National Geographic, which hasn’t yet disclosed its distribution plans for Sally, but once it is available in theaters or streaming, it is worth seeing. Perhaps by then the NASA article about the astronaut class Ride was a part of will be back online, in some form.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.