Redirecting NASA’s focus: why the Gateway program should be cancelledby Gerald Black

|

| We need to pursue human deep space programs that will inspire the public and the next generation of scientists and engineers, and which also provide the best science return. The Gateway is an unneeded and costly diversion that should promptly be relegated to the dustbin of history. |

NASA’s Artemis program is years behind schedule, its costs have ballooned out of control, and the architecture is too complex. The remedy is to eliminate costly parts of the Artemis architecture that are unnecessary, namely the Space Launch System (SLS), the Orion spacecraft, and the Gateway. My recent article described how the SLS and Orion programs could be phased out and replaced with an architecture based solely on the Starship. This article calls for an immediate end to the Gateway program.

We need to pursue human deep space programs that will inspire the public and the next generation of scientists and engineers, and which also provide the best science return. The Artemis program, with its goal of returning astronauts to the lunar surface and establishing a permanent presence on the Moon, fits this bill well. So does the new initiative to land the first humans on Mars, which was announced by President Trump in his second inaugural address. But the Gateway does not. The Gateway is an unneeded and costly diversion that should promptly be relegated to the dustbin of history.

Given the current fiscal climate, it’s unrealistic to expect a substantial increase in NASA’s budget. In fact, with the ongoing push to slash spending, it’s more likely to decrease. Therefore, to achieve our ambitious goals, we must prioritize the Artemis program and the program to land the first humans on Mars. These initiatives will require significant funding, and balancing this with the rest of NASA’s responsibilities, such as science missions and aeronautics, will be challenging. However, by eliminating the SLS, Orion, and Gateway programs and reallocating their funds, we can ensure that our focus and resources are directed where they are most needed.

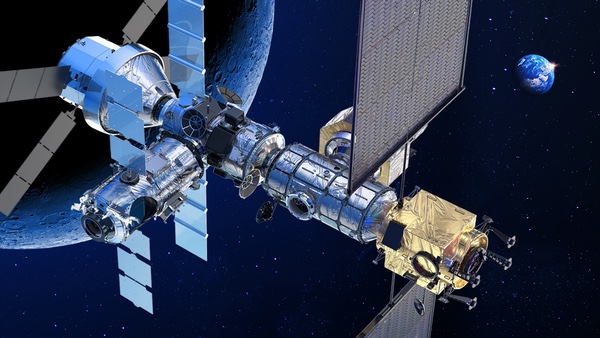

The first two modules of the Gateway are scheduled to launch together to low Earth orbit on a Falcon Heavy rocket in 2027. Then, these two modules would utilize the Gateway’s solar electric propulsion on a lengthy trip to lunar orbit. Other Gateway modules and elements would launch in later years.

Gateway costs have been escalating. According to a July 2024 report by the Government Accountability Office, NASA currently projects that the first two Gateway modules alone will cost $5.3 billion. However, this report reveals that the combined mass of the two modules has exceeded the mass target, which may affect their ability to reach the proper lunar orbit. This report also reveals that the Gateway cannot maintain attitude control when large vehicles such as the Starship lunar lander are attached. Fixing these problems will undoubtedly further drive up the costs. And logistics missions to resupply the Gateway will be an ongoing drain on NASA’s budget.

Some of our international partners have agreed to contribute modules and other elements for the Gateway. But other countries would much rather have their astronauts walking on the Moon, not just orbiting above it. NASA would do better to have our international partners develop lunar habitats, power systems, pressurized rovers, lunar landers for logistics purposes, and other needed lunar surface infrastructure.

The original rationale for the Gateway was that it is needed as a staging point for lunar surface missions and for missions to Mars. But it is more efficient to simply transport astronauts and cargo directly to and from the lunar surface, rather than detouring to the Gateway for no discernable reason. Detouring to the Gateway is detrimental, since it requires extra propellant. To make up for this, the Starship lunar lander would require more refueling flights, adding to the cost of the crewed lunar landing missions. Robert Zubrin refers to the Gateway as the “Lunar Orbit Tollbooth” in this op-ed critical of the Gateway.

Nor is the Gateway useful for human missions to Mars. It is simply more efficient to refuel in Earth orbit and transport crews directly to Mars, bypassing lunar orbit. This is the route that SpaceX has proposed for Mars missions using the Starship.

| Establishing a permanent presence on the Moon and landing humans on Mars are lofty goals that will ultimately yield untold benefits for people on Earth. But these projects will need adequate funding to be successful. |

Instead of a low lunar orbit, the Gateway uses a near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO). This orbit was chosen mostly because the underpowered Orion service module propulsion system is not capable of transporting Orion to a low lunar orbit and back. But the NRHO has drawbacks, including the fact that an abort from the lunar surface can take as long as 3.6 days to reach the safety of the Gateway. For a discussion of the drawbacks of the NRHO see this talk by former NASA administrator Michael Griffin.

The Gateway is designed to support a crew for months at a time or longer, but for what purpose? Microgravity experiments can be more easily accomplished in low Earth orbit, and lunar science can be accomplished much less expensively by robotic lunar orbiters. Certainly, the crew could perform more useful work if they were on the lunar surface.

In lunar orbit, the crew would be subjected to the deleterious effects of radiation (double that of low Earth orbit) and microgravity. Under these conditions, frequent crew rotation is prudent. But a lengthy stay is less of a problem for a crew on the lunar surface. They would be protected from radiation by a habitat covered with lunar regolith, and lunar gravity (16% of Earth’s gravity) may be less harmful than microgravity.

In the future it may well be beneficial to have a propellant depot in lunar orbit, or at the Earth-Moon L1 Lagrange point. The propellant depot could be used to store propellants produced on the Moon. But the propellant depot does not need to be a crewed facility such as the Gateway.

Establishing a permanent presence on the Moon and landing humans on Mars are lofty goals that will ultimately yield untold benefits for people on Earth. But these projects will need adequate funding to be successful. We must focus our efforts on these goals, not wasteful side projects that have no benefit other than creating jobs and lining the pockets of the contractors.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.