Power lifting: Cold War satellite reconnaissance and the Buran space shuttleby Dwayne A. Day and Harry Stranger

|

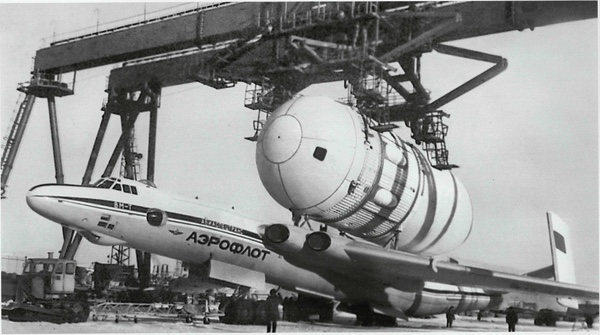

In the late 1970s, American satellites spotted new construction at the Soviet Union's Baikonur launch complex in Kazakhstan, including a new large runway that the CIA determined was for landing a spaceplane. In 1980, no large crane was visible at the airfield. In 1981 a crane nearly identical to the one outside Moscow was erected. It is seen here in summer 1982. In late 1982 it was used for removing space vehicle components off the top of transport aircraft. (credit: HEXAGON photo via Harry Stranger)  |

Eyes overhead

The Soviet Union was a highly secret society during the Cold War, and although the United States employed a vast array of sources and methods to gather information on Soviet weapons systems, the most productive tools were reconnaissance satellites. Documents were hard to obtain, spies were difficult to recruit, communications could be encrypted—but it was impossible to conceal the construction of new facilities, and new rockets and large spacecraft had to be transported, putting them at risk of detection from overhead. American photo-interpreters honed skills and techniques to identify new construction associated with Soviet space and rocket programs.

| Documents were hard to obtain, spies were difficult to recruit, communications could be encrypted—but it was impossible to conceal the construction of new facilities, and new rockets and large spacecraft had to be transported, putting them at risk of detection from overhead. |

By 1980, the CIA determined that the Soviet Union was not only building a new heavy-lift launch vehicle, but also a space shuttle to rival the NASA space shuttle program. In May 1978, the CIA detected new facility construction at Baikonur and by August 1979 determined that it was a new launch pad for a new rocket. In actuality, it was only a test stand for the rocket (something the N1 never had), but years later was modified to serve as the launch pad. Also in 1979, the Soviets began constructing a large airfield at Baikonur, and the CIA suspected that this airfield was for landing a spaceplane.

By 1981, the Soviet Union also began building a twin-bay facility. Although it is unknown how quickly the CIA determined this building’s primary function, it correctly concluded that this facility was for servicing an orbiter. By 1983, the Soviets performed launch vehicle/pad compatibility testing, making it clear what kind of vehicle the Soviets were developing. Finally, in December 1984, a satellite photographed two space shuttle orbiter vehicles at a Soviet airfield, although only one was an actual flight vehicle. The United States had limited information as to why the Soviet Union had begun such a program, but the satellite photos indicated that Soviet space shuttle efforts were extensive and expensive. (See “Target Moscow: Soviet suspicions about the military uses of the American Space Shuttle (part 1),” The Space Review, January 27, 2020.)

A major new clue—or really, two major clues—were discovered in 1981. Sometime that year, American satellites photographed Baikonur and a sprawling airbase outside of Moscow, and detected similar construction at both sites. This time it was something unique.

The large airfield that the Russians call Zhukovsky and the CIA called Ramenskoye was the Soviet equivalent to Edwards Air Force Base and the location where new aircraft were tested. In summer 1980, no large crane was spotted in satellite photos. It was erected in 1981 and first used to lift rocket components in 1982. (credit: HEXAGON photo via Harry Stranger) |

The cranes appear

The airbase outside of Moscow was referred to as Zhukovsky by the Russians, after a nearby suburb. But during the Cold War the CIA referred to it by the name of another Moscow suburb, Ramenskoye. Officially known as the Flight Research Institute (or LII), the base the Soviet equivalent to the famed Edwards Air Force Base in California, and the place was where the Soviet Union built and tested new prototype aircraft. The Soviet aircraft industry was busy in 1981, a banner year for new discoveries by American intelligence satellites. Whenever a new aircraft was spotted, the CIA gave it an alphabetical designation. In 1981, the intelligence analysts spotted RAM-J, later known as the Su-25 Frogfoot ground attack aircraft, the RAM-L, soon known as the famous MiG-29 Fulcrum, and the real prize, the RAM-P, later known as the Tu-160 swing-wing strategic bomber.

| Documents were hard to obtain, spies were difficult to recruit, communications could be encrypted—but it was impossible to conceal the construction of new facilities, and new rockets and large spacecraft had to be transported, putting them at risk of detection from overhead. |

But in addition to all the new aircraft, what intelligence analysts also spotted at Ramenskoye in 1981 was a large structure consisting of two horizontal beams with a central connector. It was a lifting device, a crane capable of picking up a large object, and with a wide enough stance so that an aircraft could be moved underneath and the object attached on its top. This discovery would have reminded intelligence analysts of a similar device constructed by NASA to enable a space shuttle orbiter to be lifted onto the back of its 747 carrier aircraft. A nearly identical structure was also photographed under construction at Baikonur on the edge of the large runway that had been started in 1979. It is unknown who in the intelligence community first made the connection, but the conclusion was obvious: something being built at Ramenskoye was going to be transported to Baikonur. Because Ramenskoye built prototype test aircraft, the Soviets must have been planning to transport one to the space center atop an aircraft.

Recently declassified photos taken by American HEXAGON reconnaissance satellites of the two locations tell a bit of the story. A July 1980 image of Ramenskoye shows no structure at the location, but by June 1982 it is clearly visible. A June 1980 image of the airfield at Baikonur does not show any structure, but one is present by June 1982. These are the only currently available satellite images of these sites during this time, but the United States certainly took many more satellite photos during these intervals, including very-high-resolution images that would have provided excellent indications of the mechanical construction of the crane.

The first test flight of any major item at LII associated with the new rocket program took place in January 1982, at a time when Moscow was almost certainly cloud covered. The first transport of any major item from Ramenskoye to Baikonur took place in December 1982. That involved the forward and aft covers of the rocket’s giant liquid hydrogen tank joined together, placed atop an M-4 bomber converted to a transport aircraft. The combination of the two looked odd, like a gangly bird carrying a large egg on its back. It is unknown if American satellites spotted this event, but the Soviet landmass was much more cloud-covered in winter, and opportunities for satellite photography are rare. An M-4 transport aircraft was initially used to ferry both rocket components and eventually the space shuttle orbiter. Later it would be replaced by a much more impressive aircraft, the mighty An-225 Mrya (“Dream,”) which was destroyed in 2022 during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The large crane was used for lifting Energia rocket components, or the Buran space shuttle orbiter, atop a Myasishchev M-4 transport aircraft. Later, the much larger, custom-built An-225 aircraft was used. Photos like this were not publicly available until decades after the end of the Cold War. The US intelligence community had to look down from orbit to see activity like this, provided the skies were clear. (credit: "Myasishchev M-4 and 3M: The First Soviet Strategic Jet Bomber," Peter Gorin and Dmitriy Komissarov) |

The June 1982 satellite photo of Ramenskoye also shows that a large object or objects were underneath the big lifting device, although the resolution of the available images is insufficient to identify them. By this time the United States had probably already observed preparations for transport of some hardware to Baikonur.

The first launch of the heavy-lift rocket, named Energia, took place from Baikonur in May 1987. The first and only launch of the Soviet Buran space shuttle, which was carried on the side of an Energia, occurred in November 1988. That flight did not include a crew, and soon the program was grounded and eventually canceled due to its expense.

With Energia and Buran both grounded, movement at the launch site and between Baikonur and Ramenskoye ceased, and for a second time the Soviet Union abandoned a heavy-lift launch vehicle program. Today, the remains of Energia and Buran are mostly slowly decaying in Kazakhstan, visited only by birds, mice, and the occasional urban explorer, willing to risk arrest for an opportunity to glimpse relics from a bygone space era.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.