The European Space Tug 1970–1972by Hans Dolfing

|

| As the development of Europe’s own rockets was not going well, discussion on telecommunication, satellites, and tugs provided different venues for space development. |

As part of these studies, the Space Shuttle was planned as reusable space delivery and return system. To go beyond LEO, an additional boost stage was necessary which became known as the Space Tug or Interorbital Transfer Tug (IOTT), and simply called “tug”. The tug mission models were to include geostationary round-trip and placement, as well as injection to planetary orbits. The tug was meant to meet payload requirements for the next decade.

The IPP and STS fostered tug studies on both sides of the Atlantic. This also relates to several EUROSPACE conferences to support the US and European cooperation between 1964 and 1970. The September 1970 conference included a note:

We are following a special approach, first, not to duplicate NASA’s work and secondly, to restrict ourselves to the field we are best qualified to handle: we have chosen to study the problem of the unmanned tug, in earth orbit, and we have decided to concentrate on transfer from the shuttle orbit to the geostationary or synchro¬nous orbit. The problem then remains what are the payload and costs versus the degree of reusability. In other words, we start from the concept of reusability which is the central feature of the new space transportation system and we apply it to the tug in a specific way. [11]

While NASA continued visionary studies between 1969 and 1971 on all aspects of the plan and was happy to discuss possible European cooperation, the American political world realized that the budgets were not there and future downscoping was in order. In spite of that, the American side studied the space tug concept in 1970. American pre-phase A studies for NASA included one by the Aerospace Corporation as well as by North American Rockwell (NAR). [6] As a report noted, “The Space Tug is a concept developed in NASA planning which would constitute a segment of a future space transportation. Its ultimate role would be to support a complete spectrum of manned and unmanned missions”[14]

Additional American studies included the “Saturn-V 4th stage,” “Chemical Orbit-to-Orbit Shuttle Study,” as well as the “Reusable Agena.” Propellant safety in space was studied as well the reuse of existing launchers and stages to form a tug.[5,16,17] Some studies emphasized a modular tug, for orbital transfer as well as lunar missions, with one or more propulsion stages and a specific impulse of 460. With missions of up to 30 days, an operational lifespan of three years was envisioned.[15]

On the European side, the origin of the European space tug studies is traced back to an European Launcher Development Organization (ELDO) meeting on April 9, 1970, where the minutes state, “As the Committee of Senior Officials of the European Space Conference are to be informed, the ELDO Secretariat will propose to its Council at its 42nd Session, to be held 27/28th April 1970, that two or three competitive feasibility studies on an interorbital transfer tug system (IOTT) should be undertaken in 1970.”[21]

As the development of Europe’s own rockets was not going well, discussion on telecommunication, satellites, and tugs provided different venues for space development with ELDO. The European space tug studies were approved July 3, 1970, with an initial budget of 500,000 MU, very roughly $500,000. Possible cooperation with NASA was firmly on the agenda.[22,29]

The European space tug pre-phase A studies were done in two parts, each roughly one year, between July 1970 to July 1972 and by two consortiums. One was led by Hawker Siddeley Dynamics (HSD) and the other by Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm (MBB). Both studied the tug in context of shuttle flights and applied to space station support, satellite placement, and lunar and interplanetary missions.

These European tug concepts were, of course, constrained by the dimensions of the shuttle payload bay at 60x15 feet (18x4.5 meters), which worked out to a the tug concept of about 4.2 to 4.4 meters in diameter with a length of 9 to 16 meters. The maximum mass the shuttle could take to LEO depended on the selected orbit, which worked out to a range of about 18 to 28 tons for polar to equatorial orbits.[26]

| The study looked at many options that ranged from a monolithic, one-size-fits-all approach all the way to a fully modular, plug-and-play concept. |

At the time, ELDO considered about 750 payloads to be launched in the foreseeable future. Therefore, one question was how flexible, modular, and reusable the tug should be to make economic sense. After all, something that can serve only one or two missions is effectively a single-use kick-stage. On the opposite side, a design that serves all payloads and mission might be prohibitively expensive. A comprise was found which balanced all criteria and could serve most of the projected payloads.

MBB study

One pre-phase A space tug study involved a total of ten European companies with MBB as the lead. Two relevant primary documents were recently located, one with 80 pages and one with 38 pages. These provide some new insights and confirm that the study consisted of a part 1 from July 1970 to January 1971 and a part 2 that continued till August 1972.[1,2,13,26]

The consortium partners included from British Aircraft Corp. (BAC), England; Société National Industrielle Aerospatiale (SNIAS), France; Construcciones Aeronauticas (CASA), Spain; Marconi, England; Selenia, Italy; L’Air Liquide, France; Eidgenössische Flugzeugwerke (FW), Switzerland; Société pour d’Etudes Technique et Constructions Aerospatiales (ETCA), Belgium; and Compagnie Industrielle Radioelectrique (CIR) from Switzerland. [1,2]

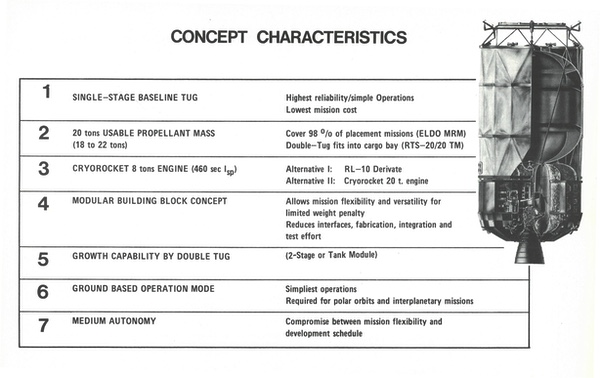

As an overview, the basic tug design, as shown in Figure 1 and 2, was a voluminous liquid hydrogen (LH2) tank on top with several smaller liquid oxygen (LOX) tanks below and a protruding engine between the LOX tanks. The visible lattice structure is structural reinforcement. Fuel cells would provide power instead of solar cells as envisioned during part 1. A medium level of autonomy was designed with three computers, which would provide backup for a single failure. Engines with thrust level of 8 to 20 tonnes were considered. Engine alternatives included the RL10 and two variants of the Cryorocket engine at either 8 or 20 tonnes thrust. All were feasible, but the eight-tonne engine with the better specific impulse of 460 was selected for the baseline tug. [1,27]

The baseline tug concept, or Reference Tug Systems (RTS), is summarized in Figure 2 and named RTS-20. This refers to a version which is fully fueled on the ground and weighed in at 20 tons. With a Shuttle in a 185-kilometer orbit at an inclination of 28.5 degrees, a fully loaded RTS-20 tug was projected to put about six tons of payload in a GEO orbit when used in expandable mode. This performance was reduced to between one and two tons of GEO payload if the tug was used in a reusable fashion and had to return to the shuttle. The delta-velocity (dV) requirement was about 4.3 kilometers per second just to go “up” to GEO plus a similar amount to return when in reusable mode. Tug support for a space station in a 55-degree orbit was considered as well.

Figure 2 : MBB baseline RTS-20. (credit: © Airbus Heritage [1]) |

With respect to its construction, the modularity of the concept was important. The study looked at many options that ranged from a monolithic, one-size-fits-all approach all the way to a fully modular, plug-and-play concept. As a fully modular design was found too expensive, the reference tug sat roughly in the middle of the modularity spectrum.

The space tug’s primary mission was to transport payloads from the shuttle’s LEO orbit to other relevant orbits. The destination orbits included MEO, GEO, as well as interplanetary destinations. For example, the use of the tug to launch a Venus or Mars mission was considered. In the reusable mode, the concept allowed an interplanetary probe with about 3.4 tons to be launched. The mass change of the tug was modeled extensively for the LEO to GEO transfer, as well as the required stellar navigation to stay on course with the use of various base orbits like 55-degree or polar orbits.

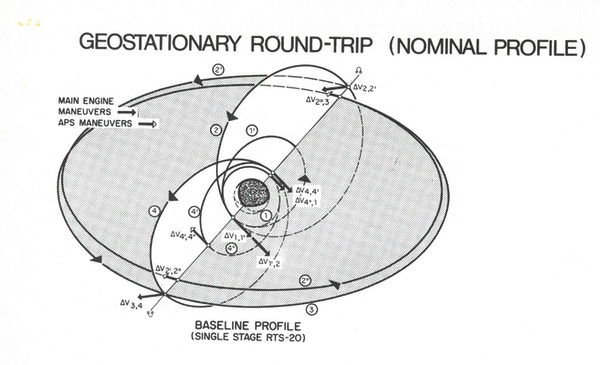

In the second part of the tug study, the focus was on the target of GEO transportation in a reusable mode, as market projections showed that would be the bulk of the missions. Figure 3 summarizes how the tug would maneuver from LEO to GEO. The first engine burn would move the tug into an elliptical orbit followed by a second burn to circularize the orbit in GEO plus a maneuver to move the payload to an elliptical orbit. As the tug was designed to be reused, corresponding maneuvers with a similar dV would follow to return to the orbiter.

Figure 3: GEO destination. (credit: © Airbus Heritage [1]) |

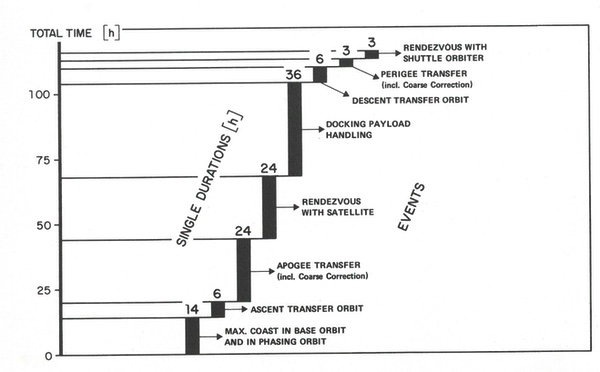

Figure 4 clarifies the durations and phasing of the tug maneuvers. The reference GEO mission and back was planned at just above 100 hours or nearly five days duration. Obviously, the engines were not running the whole time. Therefore, stability of fuel fluids needed consideration while coasting. The preferred solution was a design where the tug would rotate at 1 rpm while coasting.

Figure 4: Reusable tug mission timeline. (credit: © Airbus Heritage [1]) |

Another aspect to consider was thermal management during the long coasting. Something called “super insulation” was applied on the tanks which was a blanket of approximately 20 layers for an approximately one-centimeter-thick insulation.

For heavier GEO payloads in reusable mode, more tug performance was needed. One option was a single, heavy RTS-40, with 40 tons maximum fuel, but partially fueled to go up one shuttle and to be fully fueled once in orbit.

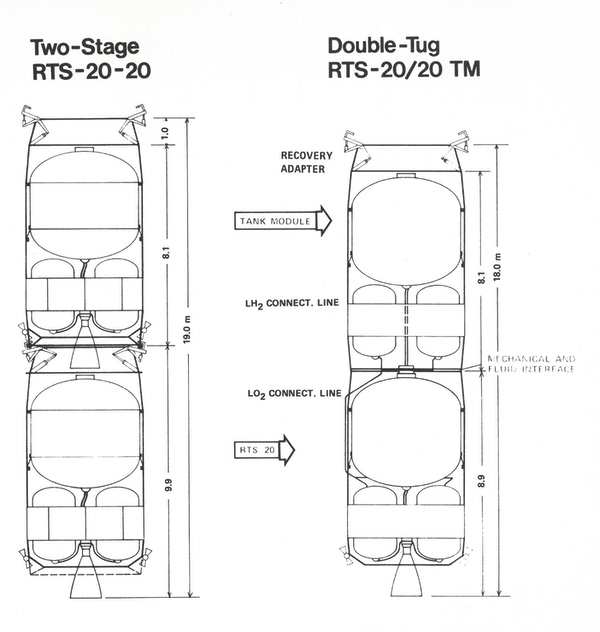

A more desirable option to increase performance was based on the modularity of design. In principle, two RTS-20 tugs could be stacked together and called an RTS-20/20 as shown in Figure 5. That would give a stack with two engines, two LH2 tanks, and eight LOX tanks total.

Figure 5: Modular tug stacks. (credit: © Airbus Heritage [1]) |

One partially fueled RTS-20 would be transported up, already mated to the payload, while the second fully fueled tug would be launched on a second mission. The combination of the two RTS-20 in space was not trivial but simplified by the sophisticated on-board computers of the tug. The docking of the two RTS-20 was designed to be fully automatic. If necessary, this scenario would call for a propellant transfer in space before use.

To improve GEO payload performance further, yet another alternative was considered, which started from a simplified version of the RTS-20 reference called RTS-20TM, with TM for Tank Module. This was designed as “just a tank and no engine.” The stack of RTS-20/20TM, as shown in Figure 5, posed a few usage questions.

One question for the RTS-20/20TM was how to assure a smooth burn to the desired orbit. As there was only one engine, what would be the most effective way to guarantee a smooth burn? This stack had two LH2 tanks and eight LOX tanks. One option was to burn the tanks of one stage first followed by the tanks of the second stage. A second option was to provide plumbing to burn all tanks at the same time. The study found concerns for a discontinuous burn when the first tug or stage would transition to second stage. Therefore, additional plumbing to run on all tanks simultaneously seemed the lesser evil and Figure 5 shows the example for the RTS-20/20TM. [1]

In general, the disadvantage for all heavy payloads was that it would require two shuttle flights and therefore cost significantly more. Clearly, the balance between reusability, cost, complexity, and payload mass was not easy at the time.

HSD study

With respect to the space tug study by the Hawker Siddeley Dynamics (HSD) consortium, one recently retrieved document contains 61 pages, lists all consortium partners, and provides many details.[4] Like the MBB study, its time frame was from July 1970 to August 1972. This particular document summarizes the second year of the study, aka “Part 2”. Its format is a report presentation which means these are not slides but basically typed lists of bullet points. In addition, there should be a wealth of information in a long list of HSD reports that are known but not retrieved yet.[13,28,29] Finally, there are three review articles about this HSD tug study.[18,19,20]

| With respect to future use and reusability, thought was given to lunar and planetary applications including the attachable landing legs, rescue operations for crewed space missions, and independent operations of the shuttle via a tank farm in orbit. |

The consortium partners are from all over Europe and were HSD, UK, as lead contractor, plus Société L’Air Liquide, France; Bell Telephone MG Co., Belgium; Contraves AG, Switzerland; Dornier System GmbH, Germany; ERNO GmbH, Germany; FIAT SpA, Italy; Fokker VFW, Netherlands; SA Engines Matra, France; and MONTEDEL SpA, Italy. [4,22]

With an eye on complexity and turnaround times, various small and large tugs were studied. Smaller tugs could be fully integrated on the ground with their payloads while larger tugs might require an extra shuttle mission and in-orbit assembly for a large payload to GEO. Therefore, this study compares designs with expendable versus reusable designs, as well as single, double, and multi-stage tugs and tanks, plus low and high autonomy for in orbit assembly.

The tug docking systems were required to attach to payloads as well as other tug stages. As an additional complication, contractors in these pre-phase A studies were also required to design a docking system independent of the final shuttle design. Guidance systems were studied for all mission phases of LEO to GEO and back using ground stations, radar while returning to the shuttle, and laser guidance for closeup maneuvers with the shuttle. Certain aspects of the tug such as propellant sloshing and maximum safety in transport were deemed solvable but details deferred to a later, more concrete study. [4, 5]

In the first part of this study, there were concepts such as two stacked 12-ton stages with a payload of 960 kilograms and the use of a single shuttle flight only. In addition, there was a concept with two 20-ton stages combined with a 2-ton payload and the use of two shuttle flights.

It was already known that the part 1 study underdelivered with a fully reusable GEO payload of less than one ton. However, the consortium came up with new ideas in part 2 of the study. Also, it was already known that the chosen shuttle LEO orbit could affect the GEO payload mass by up to 50%. For large GEO payloads of two tons or more, always at least two shuttle flights were needed given the contemporary constraints and technology. The ELDO target of 1.1-ton payload with one mission was deemed feasible with a 12-ton tug. [18,19]

In the second part of the study, with more emphasis on GEO missions, the study concentrated on a concept of a single liquid hydrogen tank forward of four separate liquid oxygen tanks. In between the LOX tanks was a single engine. Small tugs with 7.8 tons of propellant plus optional auxiliary tanks were considered as well as a large tug variant of 23 tons. [4]

With respect to future use and reusability, thought was given to lunar and planetary applications including the attachable landing legs, rescue operations for crewed space missions, and independent operations of the shuttle via a tank farm in orbit. At the time, the space traffic model and projected number of launches were very optimistic, which led to a belief that the breakeven point for the cost of conventional launchers versus such a reusable tug was only a few years away. [24]

As speculation, better technology a few decades later would have reduced the tug’s dry mass by probably 25%. The tug engine would probably have been more efficient, e.g., 10 seconds of extra specific impulse. Even with those improvements, it looks like shuttle missions with a reusable tug and GEO placement would have remained a challenge. [20]

End of the studies

Ultimately, the European Space Tug studies came to an abrupt halt in 1972. The Space Shuttle was selected on January 5, 1972, as the only part of NASA’s grand IPP plan going forward. The relationship between Europe and the US was sometimes complicated and after years of discussion, a cooperation along “clean interfaces” seemed like the best way to decide on how to move forward.

| With the hindsight of half a century, the idea of a heavy payload tugs close to the shuttle’s maximum payload mass were a bit of a stretch goal. |

After the United States and Europe had been talking for two years, the White House decided on May 18, 1972, unilaterally that an European Space Tug was a no-go. On that date, the Presidential Science advisor Edward E. David Jr. wrote a memo on “Post-Apollo relationships with the Europeans” to Henry Kissinger and Peter Flaningan and said, “I am opposed to European development of the tug.”[9] That was followed by a communication of Secretary of State William P. Rogers, who wrote to NASA administrator James C. Fletcher on June 1, 1972, that “The President has carefully studied the rationale and recommendations of your memoranda of April 29th, 1972 and May 5th, 1972 respectively, and has decided.” Including the note “3. That the Tug should be U.S. - built.” [10]

On the European side, documents shows that they heard on June 22, 1972, that “Tug is out as American position has changed” followed by an official cancellation on the European side on July 7, 1972. [7,8,12,28]

With the hindsight of half a century, the idea of a heavy payload tugs close to the shuttle’s maximum payload mass were a bit of a stretch goal. The International Space Station (ISS) orbits at 51 degrees and, at that orbit, reduced the shuttle’s cargo capacity. Reusable GEO placement of high mass payloads would have been a challenge. The tug studies’ payload projections were just a bit off the mark. Ffity years later, the GEO payloads can exceed six tons in some cases, which would have required a much higher performance tug.

Ultimately, a path was found and the space technology cooperation between the US and Europe continued. Instead of the European space tug, Spacelab was built which flew on the Shuttle in 1983. The European launcher development went through a dark period with cancellations of the Europa rocket but ultimately started a new chapter in 1975 with formation of ESA and a successful Ariane I launch in 1979. [25]

References

- D.E. Koelle et al, “Space tug systems study Pre-Phase A/Ext.”, Final presentation, Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm (MBB), 80 pages

- “European Space Tug System Study, Pre-Phase A Study Summary”, CTR 17/4/31, Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm, MBB Report No. UR-V-38(71), N73-19889, 38 pages, February 1971.

- “Study of the Use of Post-Apollo Transportation Elements for High-Energy Solar System Exploration Missions”, Estec Contract 1515/71 EL, Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm, MBB Final Report No. URV-52(72), N72-33878, 166 pages, June 1972.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG Phase A Study Part 2: Report Presentation”, Hawker Siddeley Dynamics Limited, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England, HSD-TP-7264, British Library Wq6/9239, 5 October 1972.

- “IN·SPACE PROPELLANT LOGISTICS AND SAFETY Volume I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY”, North American Rockwell, Downey, CA, NAS8-21692, N72-30797, SD72-SA-0054, Volume 1 to 3, 23 June 1972

- “Analysis of a reusable space tug”, North American Rockwell, NAS9-10925, N71-21453, NTRS 19710011978, June1970, Volume 2 out of 6.

- ESC-637, “Report of the ESC Delegation on discussion held with the U.S. Delegation on the European participation in the Post-Apollo program”, Washington 14-16 June 1972, European Space Conference (ESC), ELDO, ESC-637, CSE/CS(72)15, Neuilly, France, 22 June 1972

- ESC-654, “Tug Studies”, Letter by J.P. Causse (Deputy Secretary General ELDO) to P. Culbertson (NASA), European Space Conference (ESC), ELDO, ESC-654, CSE/CS(72)32, Neuilly, France, 22 June 1972

- “Post-Apollo relationships with the Europeans”, US Department of State, EO 12958, May 18th, 1972

- “Post-Apollo relationships with the Europeans”, US Department of State, EO 12958, June 1st, 1972

- J.P. Causse, Deputy Secretary General ELDO, Speech as part of “EUROSPACE”, 4th Europe-USA space conference, 1970, Venice, pp 407-422, 22 September 1970.

- G. Collins, “Europe in Space”, 1990, ISBN 978-0-312-05316-1

- “Index of ELDO Publications”, ELDO SP-1006, September 1977

- A. S. Kiersarsky, et al, “Pre-Phase A Tug Studies - Case 105-4”, Bellcomm, NTRS 19790072717, 3p, June 30, 1971

- P. Culbertson, “Space Tug”, N71-18430, Presentation by Philip E. Culbertson, Director, Advanced Manned Missions program, NASA at ELDO/NASA Space Transportation System Briefing, Bonn, Germany, July 7-8 1970

- “Reusable Agena Study”,”Final report, Executive Summary”, Lockheed Missiles & Space Company (LMSC) for NASA CR-120362, NAS8-29952, LMSC-D383069, NTRS 19740023215, Volume 1 of 2, 1973-1974.

- “Shuttle/Agena Study”,”Final report”, Lockheed Missiles & Space Company (LMSC), NAS9-11949, LMSC-D152635, NTRS 19720013175, 25 February 1972.

- D.G. Humphries, “The Choice of Space Tug”, Hawker Siddeley Dynamics, JBIS Vol. 26 Iss. 1, pp. 1-6, January 1973.

- G.J.N. Smith, C.E. Allen, “Space Tug Design”, Hawker Siddeley Dynamics, JBIS Vol. 25, Iss. 12, pp. 697-708, December 1972.

- D. Stott, M. Hempsell, “The European Space Tug: A reappraisal”, British Aerospace (BAe) , JBIS Vol.34, Iss. 7, pp. 294-299, July 1981.

- ELDO-1421, “Cooperation with NASA/ Approval and financing of a European competitive study on an inter orbital transfer tug (IOTT)”, ELDO/C (70)9 rev., 6 pages, Neuilly, 9th April 1970.

- ELDO-1439, “Decision on the approval and financing of a study concerning the interorbital transfer tug with a view to a possible cooperation with NASA”, ELDO/C(70)27(Final), 6 pages, Neuilly, 3rd July 1970.

- J.W. Cornelisse, K.F. Wakker, “Geosynchronous Space Tug Missions”, Report VTH-171, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, 133 pages, August 1972.

- R.G. Reichert, “Space Tug in ‘Kit-Type’ Philosophy, A possible European Contribution to the US Post Apollo Program”, in “ESTRATTO DAGLI ATTI UFFICIALl DELL’XI CONVEGNO INTERNAZIONALE SULLO SPAZIO”, II-6, Rome, April 1971, pp155-171, Dornier-System GmbH, Friedrichshafen (Germany).

- J. Krige, A. Russo. “A History of the European Space Agency, 1958 – 1987”, Volume I, The story of ESRO and ELDO, 1958 - 1973, ESA SP–1235, April 2000.

- Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm, “European Space Tug System Study, Pre-Phase A Study”, reports (not yet located)

- H. BREHME, “DESCRIPTION OF THE SPACE TUG MISSION COVERAGE COMPUTER PROGRAM”, MBB TN-R-01-191/72, X76-10392, 25p, 7 April 1972

- H KELLERMEIER, “CANDIDATE TUG SYSTEMS DEFINITION”,MBB TN-R01-192/72, X76-10393, 28p, 10 April 1972

- BOHNHOFF and KIENLEIN , “CANDIDATE TUG PERFORMANCE”, MBB TN-R01-193/72, X76-10394, 38 p, 21 April 1972

- W. SCHULTZE, “TUG OPERATIONAL PHASES AND PROCEDURES”, MBB TN-R01 -198/72, X76-10395, 20p, 13 June 1972

- W. SCHULTZE, “THE TUG AUTONOMY AND MISSION SUCCESS. PROBA¬BILITY REQUIREMENTS”, MBB-TN-R01-200/72), X76-10396, 16p, 26 Jun. 1972

- H. KELLERMEIER , “TASKS AND PROBLEMS FOR THE DESIGN OF AN INTERORBITAL SPACE TUG”, MBB-UR-62/70, X76-11032, 3rd DGLR Jahrestagung 1970, Dusseldorf. 3-4 Dec. 1970

- “PHASE A STUDY SPACE TUG. COMPREHENSIVE TUG CONCEPTS SIZE AND SYSTEMS ANALYSIS VS MISSION REQUIREMENT MODEL COVERAGE AND PROGRAM COST. VOLUME 2: SUMMARY PART 1,” MBB-URV-53-72, X76-11646, ELDO-CTR-17/4/64, 61p , May 1972

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG - PHASE A STUDY”, MBB UR-V-53(72), ELDO CTR 17/4/64. May 1972

- “EUROPEAN PHASE A STUDY SPACE TUG. COMPREHENSIVE TUG CONCEPTS SIZE AND SYSTEMS ANALYSIS VS. MISSION REQUIREMENT MODEL COVERAGE AND PROGRAM COST, VOLUME 2 SUMMARY PART 1 Final report”, MBB-URV-53-72-VOL-2-PT-1, N73-27765, ELDO CTR 17/4/64, 68p, May 1972

- “PHASE A STUDY SPACE TUG. VOLUME 3: SYSTEM DESIGN RTS-25 Final report”, by MBB, British Aircraft Corp, Marconi et al, MBB URV 56-72, X76-11647, ELDO CTR 17/4/64, 606p, September 1972

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG SYSTEM STUDY. PRE-PHASE A STUDY EXTENSION. Final Report”, by MBB, British Aircraft Corp, Marconi et al, MBB-URV-44-71, N73-19890, ELDO CTR 17/4/31, 513p, August 1971.

- H.SCHWEIG, “SOLAR AND NUCLEAR-ELECTRIC PROPULSION STAGES FOR TRANSFER INTO A 24H-ORBIT: FEASIBILITY STUDY”, MBB-DSP-6-427-0, X76-10157, ELDO-CTR-17/4/11, 229 p, March 1969

- “DESIGN STUDY FOR A MODULARIZED SOLAR ELECTRIC PROPULSION SYSTEM (SEPOS) ELDO LAUNCH Vehicle”, MBB UR-V-62-73, X76-10160, 183p, August 1973

- C. DONNAY, ANALYSIS OF TUG STUDIES MADE BY HSD AND MBB: ELECTRICAL POWER SYSTEM (POWER SUBSYSTEM), X76-11780, 10p, 23 Feb. 1972 - Cryorocket reports (not yet located)

- “SPACE TUG ENGINE STUDY, PHASE A ELDO Launch Vehicle Studies Final report”, X76-10169, ELDO-CTR-17/3/174, 118 p, 21 August 1972

- “STUDY OF A THERMAL NUCLEAR PROPULSION SYSTEM”, N73-24681, ELDO CTR-17/3/129, 125p, 28 Feb 1972 - Hawker Siddeley Dynamics, “European Space Tug System Study, Pre-Phase A Study”,

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG Pre-Phase A Study report”, HSD-TP-7227, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19891, 304p, January 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY Summary report”, HSD-TP-7264, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19900, 362p, August 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY, PART 2, Volume 1, Introduction, organization, planning”, HSD-TP-7264-VOL-1, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19901, 72p, August 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY, PART 2, Volume 2: Special purpose tug, reference tug system Final report”, HSD-TP-7264-VOL-2, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19902, 85p, August 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY, PART 2, Volume 3: Propellant and propulsion”, HSD-TP-7264-VOL-3, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19903, 89p, August 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY, PART 2, Volume 4: Guidance, control, rendezvous, integrated electronics”, HSD-TP-7264-VOL-4, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19904, 241p, August 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY, PART 2, Volume 5: Structure, configuration and kits”, HSD-TP-7264-VOL-5, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19905, 174p, August 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY, PART 2, Volume 6: Performance, economics, reliability, weights, costs and programs”, HSD-TP-7264-VOL-6, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19906, 253p, August 1971. - Hawker Siddeley Dynamics, “European Space Tug System Study, Pre-Phase A Study”, reports (not yet located)

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PART 2 STUDY DIGEST”, HSD-TP-7264A, N73-19892, 110p, 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY APPENDIX 1: STUDY LOGIC AND PLAN”, HSD-TP-7227-APP-1, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19893, 31p, January 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY APPENDIX 2: VEHICLE SELECTION AND ECONOMICS”, HSD-TP-7227-APP-2, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19894, 141p, January 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY APPENDIX 3: PROPELLANT CONTROL AND PROPULSION”, HSD-TP-7227-APP-3, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19895, 103p, January 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY APPENDIX 4: GUIDANCE CONTROL AND RENDEZVOUS”, HSD-TP-7227-APP-4, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19896, 165p, January 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY APPENDIX 5: INTEGRATED ELECTRONICS”, HSD-TP-7227-APP-5, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19897, 163p, January 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY APPENDIX 6: STRUCTURE AND CONFIGURATION”, HSD-TP-7227-APP-6, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19898, 166p, January 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY APPENDIX 7: WEIGHTS, COST AND DEVELOPMENT”, HSD-TP-7227-APP-7, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19899, 77p, January 1971.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG PRE PHASE A STUDY PART 1 Executive summary”, HSD-TP-7316, ELDO CTR-17/7/44, N73-19907, 82p, 1972.

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG. PHASE A STUDY, PART 2”, Volume 1, HSD-TP-7336-PT-2-VOL-1, X76-10346, 417p, August 1972

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG. PHASE A STUDY, PART 2”, Volume 2, HSD-TP-7336-PT-2-VOL-2, X76-10347, 403p, August 1972

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG. PHASE A STUDY, PART 2”, Volume 3, HSD-TP-7336-PT-2-VOL-3, X76-10348, 321p, August 1972

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG. PHASE A STUDY, PART 2”, Volume 4, HSD-TP-7336-PT-2-VOL-4, X76-10432, 226p, August 1972

- “EUROPEAN SPACE TUG. PHASE A STUDY, PART 2”, Volume 5, HSD-TP-7336-PT-2-VOL-5, X76-10349, 388p, August 1972

- D.G. Humphries, “THE CASE FOR A SMALL EUROPEAN SPACE TUG”, HSD-TP-7344, X76-10787, 16p, September 1972

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.