The new wave of asteroid mining venturesby Jeff Foust

|

| “We made it through our whole test campaign and we’re feeling pretty good about it,” Gialich said. “But anybody that’s flown in space knows feeling good is the first sign that you [expletive] it up.” |

AstroForge is among the handful of startups that mark a new wave of asteroid mining ventures, years after companies like Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources faded away. These companies, hoping not to repeat the mistakes of their predecessors in their quest to tap into the wealth promised by asteroids, are raising money and building spacecraft to serve as precursors for later mining missions.

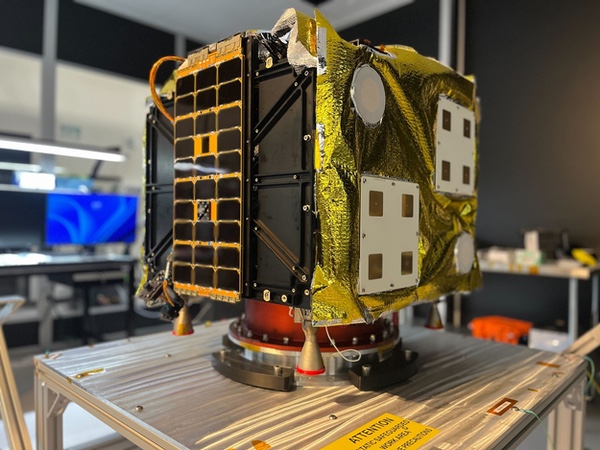

In the case of AstroForge, that meant quickly developing its first asteroid reconnaissance mission. The company, which has raised $55 million to date, including $40 million in a Series A round last August, decided to take development of Odin in-house last year after it ran into problems with the company it had hired to build it.

“I thought that the chances of us getting there with the vendor we had selected had gone to zero,” Gialich said last summer, a few months after that insourcing decision. (He did not identify the vendor, but AstroForge had previously disclosed it was working with smallsat manufacturer OrbAstro.)

Development of Odin became a sprint for AstroForge because the company did not want to lose its ride: a secondary payload opportunity on the Falcon 9 launch of the Intuitive Machines IM-2 lunar lander. “I told the team, we’re either on IM-2 or we’re not a company. Those are our two options,” he said last summer.

By late January, Odin was ready. That required many long hours as well as some unconventional testing techniques: AstroForge posted on social media an image of the spacecraft rolled out into a parking lot. “Testing out our long range imagers on the local birds,” it said.

AstroForge was finally ready to disclose the asteroid Odin would visit: 2022 OB5, a near Earth asteroid about 100 meters across thought to be metallic. The company had not publicly disclosed that object, to the consternation of scientists and others in the industry.

“There’s been a lot of pushback on what asteroid we’re going to from the scientific community,” he said before launch, concluding it was now time to work with astronomers. “I would like more information on the asteroid, and a great way to get more information before launch is to announce which one it is for amateur astronomers to go look at.”

If all went well, Odin would fly by 2022 OB5 about 300 days after launch, collecting data to see if the asteroid was, in fact, metallic. If it was, it could become a prime target for future missions planned by AstroForge to mine the asteroid and refine those materials, returning precious metals to Earth.

That is, if all went well. “I am [expletive] terrified,” he said, then describing how he told the team that they should be scared given how fast the company went in building Odin. “We made it through our whole test campaign and we’re feeling pretty good about it. But anybody that’s flown in space knows feeling good is the first sign that you [expletive] it up.”

He argued, though, it was better to try and fail—fail fast, to use the term bandied about by many startups—than to wait years for a perfect spacecraft. “We’ve got to go for it. I respect Planetary Resources a lot, but they didn’t have the balls to try. We’ve got the balls to try. Hopefully our brains are good enough to pull it off.”

On February 26, that Falcon 9 carrying IM-2, Odin, and two other secondary payloads lifted off from the Kennedy Space Center. Soon, AstroForge was running into problems with Odin.

The company originally thought they were having problems with their ground station because while they were getting a carrier signal from the spacecraft, there was no telemetry associated with it. Gialich said in a video update February 28 that AstroForge has run into a variety of issues with those ground stations, from broken equipment to terrestrial interference, in the days leading up to the launch.

| Its best guesses are that either the spacecraft couldn’t properly deploy its solar panels and thus had limited power or that it is tumbling and is not able to point its antennas towards Earth. |

Another possibility was that Odin was in a “really slow, uncontrolled tumble,” but he appeared to dismiss that in favor of the ground station problems. The company planned steps to get the spacecraft to turn on a power amplifier for its transmitter, he said, with the goal of “getting more data from the spacecraft so we can make sure its state is in a good place.”

However, by March 1 AstroForge had returned to the hypothesis that Odin was in a slow tumble. “There is still a chance that we are going to be able to recover the vehicle,” Gialich said, “but I think we all know that hope is fading.”

On March 6, AstroForge acknowledged that Odin’s mission was over. The company published a detailed, blow-by-blow account of its efforts to contact Odin and the problems it experienced. Its best guesses are that either the spacecraft couldn’t properly deploy its solar panels and thus had limited power (a possibility detected in pre-launch testing), or that it is tumbling and is not able to point its antennas towards Earth.

AstroForge is unbowed by the failure. The company says it spent just $3.5 million on Odin and is already working on its next spacecraft, Vestri, targeted for launch as a secondary on the IM-3 mission Intuitive Machines plans to launch as soon as early 2026. Vestri will be bigger with improved propulsion and avionics. The company also plans to hire “principal-level” engineers with spacecraft experience to augment a workforce that had more experience on launch vehicles.

Karman+ plans to launch its first asteroid mission, called High Frontier, as soon as 2027. (credit: Karman+) |

Mining asteroids for water and propellant

As AstroForge was preparing for the launch of Odin, another startup announced its interest in asteroid mining. Karman+ said February 19 it raised $20 million in seed funding from several investors for its work on asteroid mining missions.

While AstroForge is focused on mining metallic asteroids for precious metals, Karman+ is looking for other classes of asteroids that might harbor hydrated minerals. The company wants to mine those asteroids and extract the water from them.

Teun van den Dries, co-founder and CEO of Karman+, studied aerospace engineering in college but went into software, founding a company that did data analysis for commercial real estate. He kept tabs, though, on the industry from the sidelines.

“The prior generation of asteroid mining companies were friends that I cheered on from the sidelines, and watched them try and then subsequently collapse,” he said in an interview. “This will happen in my lifetime. Someone will make this work.”

After he sold his first company, he turned his attention to asteroid mining. “I’ve thought about this is as, what is the highest leverage thing I can do with my time?” he said. “This is definitely one of them. If this works, it will be transformational for both the space economy as well as Earth’s economy.”

| “I’ve thought about this is as, what is the highest leverage thing I can do with my time?” van den Dries said. “This is definitely one of them.” |

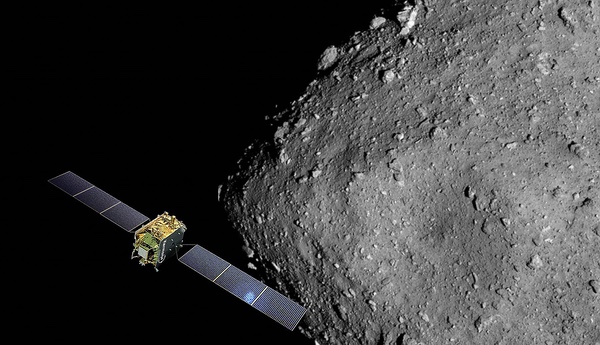

Karman+—the name, he said, is based on the approach of harnessing space resources, those above the 100-kilometer Kármán Line, to do things in space not possible today—is working on its first mission, proposed for launch in 2027. It will go to an asteroid and attempt excavate material on the “kilogram scale,” or much more than the grams of samples collected by Japan’s Hayabusa missions or NASA’s OSIRIS-REx.

Like AstroForge, the company has moved much of its spacecraft development in-house. “We initially figured that we’d be able to outsource roughly 80% of the spacecraft. In the last two years, that has shifted to roughly 20%,” he said, citing difficulties in getting components. The funding the company has raised is more than enough to complete the spacecraft, which van den Dries says should cost less than current estimates of $17 million.

That first mission won’t attempt to bring any asteroid material back to Earth. “We optimized this mission to be low cost and capable of doing as many of the tests and things that we want to do at the asteroid,” he said, including testing navigation and instruments as well as gathering asteroid material.

The company is focused on water because that can serve as fuel—either on its own or broken down into hydrogen and oxygen—for refueling spacecraft. The problem, though, is that very few spacecraft use such propellants, preferring hydrazine or other storable propellants for chemical thrusters or xenon and other noble gases for electric thrusters.

The approach Karman+ is taking is to be the initial customer for that asteroid-derived water. “Our spacecraft is, in a very literal sense, dual use. We have a mining configuration, which is the one that is going out to the asteroids,” van den Dries said. “But we also have what is effectively, if we swap out the excavation equipment for a grappling arm, a very effective tow truck.”

| “There’s a debate to be had about whether space mining is legal. We can discuss whether it’s technologically feasible, economical, within our jurisdiction, or if it’s even safe,” said Rep. Dexter. |

That tow-truck version of the Karman+ spacecraft would serve as a life-extension vehicle, similar to what SpaceLogistics, a Northrop Grumman subsidiary, has been doing for several years with its Mission Extension Vehicles. The spacecraft would attach to a satellite and take over maneuvering.

“Rather than refuel the customer spacecraft, we refuel our own tow truck, which is a system that we control end-to-end,” he said. “Because we can refill our own spacecraft, it drastically reduces our internal cost for these kinds of missions.”

He dismissed competition from other orbital transfer vehicles, including those that might take advantage of the low-cost launch promised by SpaceX’s Starship. “That would be true if cheap launch existed. There's no such thing,” he argued. “SpaceX does a great job marketing and then raises their prices by 10% every year, and has done that every year for the last decade.”

He added that he did not see Starship as a threat for GEO missions since that vehicle requires refueling to get to GEO. “We have an order of magnitude cost difference in our benefit because of the refueling architecture that is in a GEO configuration impossible to beat,” he said, adding that Karman+ did not plan to serve the low Earth orbit market.

Space mining vs. Spaceballs

Asteroid mining has gotten renewed attention from Congress as well, with the oversight subcommittee of the House National Resources Committee holding a hearing on the topic February 25.

“What seems like a far-off concept is no longer so,” said Rep. Paul Gosar (R-AZ), chairman of the subcommittee. “Resource extraction in space is right around the corner.”

Much of the 90-minute hearing, though, had little to do with asteroid mining. One of the witnesses, Richard Painter, a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School, acknowledged he had little expertise in asteroid mining, but instead discussed that, if asteroid mining was supported with public money, the taxpayers should get a return on that investment. He also discussed conflicts of interest where government officials might benefit personally from public expenditures.

That included Elon Musk, the de facto head of the Trump Administration’s Department of Government Efficiency while also remaining CEO of SpaceX. “Mr. Musk can’t be involved with SpaceX and having anything to do with space mining in the United States government. That would just be flat-out corrupt,” he said. (The US government has, so far, not made any sizable direct investments in any space mining ventures, whether or not they are connected to SpaceX.)

There were two executives on the panel representing space resources companies. Steven Place, senior policy advisor for AstroForge, offered several recommendations, ranging from having the government be the “offtaker of last resort” for space mining companies and for NASA to provide companies with more access to the Deep Space Network for their asteroid mining missions.

Saurav Shroff, CEO of Starpath, offered his own recommendations on topics such as increasing the speed of launch licensing and modernizing planetary protection rules. He said his company is working on technology to create a “rocket propellant refinery” on the Moon. He claimed that system would be ready to launch by the middle of next year “that is twice as powerful as the most powerful satellite ever made, the International Space Station, at a fraction of the cost.” He didn’t elaborate on that system and in what ways it was more “powerful” than the ISS, or how it would get it to the Moon. The company has announced only $12 million in funding to date.

The committee members didn’t seem interested in the recommendations from Place or Shroff. “There’s a debate to be had about whether space mining is legal. We can discuss whether it’s technologically feasible, economical, within our jurisdiction, or if it’s even safe,” said Rep. Maxine Dexter (D-OR), ranking member of the subcommittee.

“But the key question for today is whether investing in such an expensive venture at this time is necessary to meet our critical mineral needs. The answer to that question is decidedly no,” she concluded.

| “What I've noticed about aerospace is it's still full of a bunch of people that are low risk individuals,” Gialich said. “We're the one that is saying, like, we think we can take more risk and we think we can actually change the world.” |

Rep. Jared Huffman (D-CA), ranking member of the full committee, offered even sharper criticism, noting that space mining did not appear to be in the jurisdiction of the committee and that other issues, like cuts to federal agencies within the committee’s jurisdiction, were more important. “For those who have been longing to a sequel to the movie Spaceballs, this is your lucky day,” he said. “For everyone else, we can marvel at just how tone-deaf House Republicans are.”

He argued the companies testifying were seeking federal subsidies for their work through NASA support and a “price floor” for space resources they mine. “It does take some space balls, in this moment, to come in and ask for federal money.”

Even a Republican member was skeptical of the utility of asteroid mining. “Why is it that we are literally looking to outer space for these minerals, minerals we’re blessed with right here in the United States of America?” asked Rep. Pete Stauber (R-MN).

He asked one witness, Misael Cabrera of the University of Arizona, how much cheaper it would be to obtain the same amount of minerals—121 grams—as OSIRIS-REx did from the asteroid Bennu for $1.2 billion. “I can’t, frankly, do that math in my head,” Cabrera responded, but acknowledged it would be “much more inexpensive.”

Congress might be skeptical of asteroid mining, but true believers like AstroForge’s Gialich are pressing ahead. “What I've noticed about aerospace is it's still full of a bunch of people that are low risk individuals,” he said in the company’s post about the end of the Odin mission. He contrasted it to AI conferences where people are “high on drugs” and claiming they’re going to “make God.”

“And you’re like, where are those people in the aerospace community? We’re that person, right? We're the one that is saying, like, we think we can take more risk and we think we can actually change the world.”

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.