Space weather and spaceflightby Jeff Foust

|

| “Satellite collision avoidance is really not very robust to geomagnetic storms,” Parker said. “We basically have no ability to do collision avoidance in low Earth orbit during a storm.” |

Certainly, much the attention given to space weather has focused on the effects a major solar storm would have on communications, the power grid, and more. During the Space Weather Workshop last month in Boulder, Colorado, in a hotel a few minutes’ drive from the SWPC offices, many of the sessions focused on the terrestrial impacts of space weather in areas from aviation to precision agriculture: interference with GPS signals during the major “Gannon Storm” last May, at the peak of corn planting season, led to one estimate of $500 million in losses. Other sessions examined issues in communicating space weather to various audiences (including a panel that included the author.)

It was also clear from the workshop that the interest in space weather extends into space. As the number of satellites sharply increases, so does the concern about how space weather, directly or indirectly, affects those spacecraft and space situational awareness (SSA) in general. And, as NASA prepares to send humans to the Moon for the first time in more than 50 years, the agency and others are thinking about how to prepare for any solar storms that may take place.

“No ability to do collision avoidance”

For many years, satellite operators were concerned about how space weather might affect their satellites by damaging their electronics. While that concern remains, there is growing interest in how solar storms, by heating up and expanding the upper atmosphere, affect the orbits of satellites in low Earth orbit, particularly as megaconstellations are being deployed there.

That was noticed last year during both the Gannon Storm and another geomagnetic storm in October. In a talk at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in December, William Parker of MIT said that those events led to “mass migrations” of thousands of SpaceX Starlink satellites, which used their autonomous systems to raise their orbits simultaneously in response to the increased atmospheric drag caused by the storms.

He recapped that analysis at the Boulder workshop last month, noting that the mass maneuvers disrupt planning by other operators for collision avoidance. “When you have half of all the active satellites maneuvering at one time, you can basically throw all of that analysis out the window,” he said.

“Satellite collision avoidance is really not very robust to geomagnetic storms,” he said, due to those maneuvers as well as the errors in orbital positions caused by atmospheric drag from the storms. “We basically have no ability to do collision avoidance in low Earth orbit during a storm.”

Others at the meeting offered similar assessments. Dan Oltrogge of COMSPOC, a commercial SSA company, said the Gannon Storm created errors in the positions of satellites as large as hundreds of kilometers. Errors that large, he concluded, “really invalidates doing spaceflight safety.”

Satellite operators, they said, need better forecasts—or, at least, more information about the uncertainties of those forecasts—as well as better models of both solar activity and the effects that activity has on the atmosphere.

Some companies have already been burned by those forecasts. In 2019, Capella Space designed its Whitney series of radar imaging satellites based on predictions by SWPC for the upcoming solar cycle. Those predictions underestimated the amount of activity in the cycle, now reaching its peak, and thus the impact on those satellites.

| “The real answer we’re trying to get it is the answer to the question, ‘How long do I have before my satellite burns up?’” Shambaugh said. |

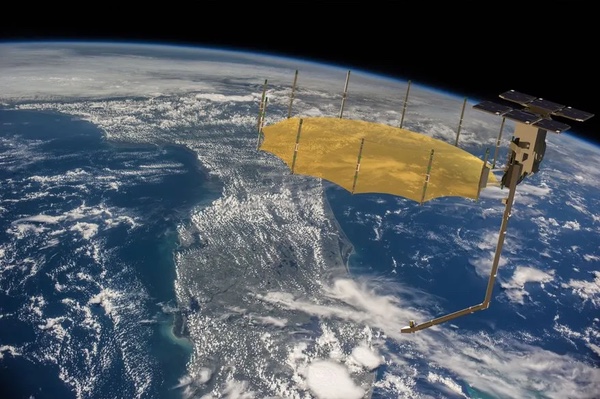

Scott Shambaugh, formerly a senior engineer at Capella, described those challenges in a paper last year. The higher solar activity increased atmospheric drag by a factor of two to three, increasing drag that shortened the satellites’ lifetime, particularly for the Whitney satellites with their large deployable radar antenna. The company scrambled to mitigate the problem but still lost six satellites in 2023 as they reentered earlier than planned.

“This represents a gap between the academic community and the operators in industry,” Shambaugh said at the workshop, one he’s seeking to fill. At the meeting he announced he has started a new company, called Leonid Space, that will offer satellite operators improved modeling of space weather to more accurately predict when their satellites will reenter.

“The real answer we’re trying to get it is the answer to the question, ‘How long do I have before my satellite burns up?’” he said. His company demonstrated that with an analysis of the four TROPICS cubesats NASA launched in 2023 to study tropical storms. The project initially thought the satellites could remain in orbit for up to nine years, revising that to five to six years last year. But the Leonid analysis finds that all four will likely reenter this July and August.

SWPC’s Space Weather Prediction Testbed will host an exercise to prepare for the Artemis 2 mission. (credit: J. Foust) |

Preparing for Artemis 2

Interest in space weather extends to human spaceflight. Artemis 2, scheduled to launch next year, will be the first mission since Apollo 17 in 1972 to send humans beyond low Earth orbit, and thus outside the protection of the Earth’s magnetosphere. That has put a new focus on the ability to predict and respond to space weather events with human lives on the line.

To prepare for that mission, SWPC will be hosting an exercise at the end of this month, extending into early May. The exercise will bring together NASA, NOAA, and other experts to examine how they would respond to a space weather event during Artemis 2 mission. The exercise will use actual data from a previous space weather event, although the participants won’t be told in advance which event.

“The goals we have for this exercise include enhancing our preparedness for human spaceflight endeavors, focusing on the Artemis 2 mission,” said Hazel Bain, a research scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder. That includes, she said, “really trying to explore and evaluate new space weather products and applications.”

That also involves embracing a new mindset for spaceflight operations. “Things are going to be different when we go to the Moon because we’re not under the magnetic field most of the time, so it’s always a constant threat,” said Steve Johnson of NASA’s Space Radiation and Analysis Group. “It’s a lot different from what we’re used to for station operations.”

That work featured analysis of the Orion spacecraft using data from several major solar proton events to determine when the crew would need to take action. On Artemis 2, which will fly a free-return trajectory around the Moon, there is nothing they can do to cut the mission short once they leave Earth orbit.

Instead, if a major solar storm takes place, the four-person crew will have to build a makeshift storm shelter inside Orion. “It takes all the waste bags and all the storage bags and making a little pillow fort,” said Rob Chambers of Lockheed Martin, prime contractor for Orion. “And then you climb in and cuddle up in a spoon position for as long as you guys say we have to stay.”

“That’s not like a wonderful way to explore,” he added, but noted it was the only option in the near term.

| “To make use of those six days“ of an Artemis landing, Johnson said, ”we have to have some way to try to figure out how to manage that exposure within acceptable limits.” |

There have been tests of other ways to protect astronauts from radiation, including a vest called AstroRad that was flown on Artemis 1. One instrumented manakin wore the vest and an identical one did not. Chambers said that the vest reduced the effective radiation dose by 40% to 61%, suggesting that it could allow astronauts to briefly exit the storm shelter to perform work elsewhere in Orion. “We can do more than cuddle up under a pillow fort when these things happen.”

Johnson said his group was thinking ahead to Artemis 3 and beyond, when astronauts are on the lunar surface. That involves balancing the safety of the astronauts on the Moon with the tight timelines of at least those early lunar landings.

“When an event starts, how soon do we have to come in to avoid an excessive exposure and, as an event decays, when can we go back out and not have excessive exposures?” he said. “We just can’t sit inside the whole time.”

Those early missions, he noted, will spend six days on the surface, a timeline dictated by the use of the near-rectilinear halo orbit for Orion and the Gateway. “To make use of those six days, we have to have some way to try to figure out how to manage that exposure within acceptable limits.”

How a shift of SWPC from NOAA to DHS might affect support for the Artemis missions, or improving forecasts for satellite operators, is uncertain. But space weather is increasingly no longer just a terrestrial issue.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.