The real space race: China will send a crew to orbit Mars by 2050by Kristin Burke

|

| By applying lessons learned from China’s release of information on its timeline for a crewed lunar landing, this report shows that there is already Chinese top leadership support for a crewed Martian mission. |

This report considers an initial orbit-only mission, to accurately reflect what the CAS forecast says and to support follow-on studies. The CAS technology forecast specifically distinguished between a “crewed Lunar landing around 2030” and “crewed Mars exploration around 2050,” i.e. it does not say Mars landing.[4] Within this scope, this report discusses what Chinese researchers have said about relevant launch windows and highlights select technology milestones for space watchers to track. Last, this report poses three questions policymakers should consider when determining the implications for the United States, as well as flags alternative space missions the PRC could use to celebrate its second centennial.

What did we learn from the Lunar case?

This report applies two lessons learned from China’s gradual announcement of its plan to land a crew on the Moon:

- Chinese statements from informed individuals may be just as authoritative as statements from official CMSE representatives.

- Limited publicly available information on key technologies to enable the Chinese mission shouldn’t be a strong reason to discount statements from informed individuals. In other words, the two types of information are separate but equal indicators.

Generally speaking, when a Chinese official makes an announcement to national Chinese media, outside observers have confidence that those statements reflect top leaders’ views. The reason for that is because the CCP manages the media and PRC officials are sensitive to toeing the party line to protect their careers. This fact influenced seasoned Western space watchers to discount State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) statements about a Chinese crewed lunar landing.[5] To some, it seemed more likely that the SOE rocket engineers’ business incentives, rather than CCP support for a lunar mission, drove the engineers’ proposed timelines. (SOE economic success, after all, is also a CCP goal.)

For example, just after CAS published its 2009 space technology forecast, two vocal space SOE representatives—now-retired China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT) representative Long Lehao and now retired China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) representative Ye Peijian—stated that, “the [crewed lunar] mission is technically possible in 2025.”[6] Those same representatives in 2021 and in 2022 said, “a crewed landing [on the Moon] is entirely possible by 2030.”[7] At last, in mid- 2023, CMSE announced that China will attempt to land taikonauts on the Moon “before 2030,” and outside observers finally accepted their timeline.[8]

Regarding lesson one, Western space watchers do not fully understand the relationship between China’s official messaging and SOE statements, especially in a national strategic industry with a long legacy like the space sector. In the case of assessing China’s commitment to a crewed lunar landing, Western space watchers had less confidence in SOE and China National Space Administration leaders’ (CNSA) statements.[9] Instead, space watchers waited for official announcements from CMSE because CMSE is directly in charge of the astronaut program.[10] In this case, some SOE representatives turned out to be well informed. It is still important to be cautious, however, because the rising generation of Chinese space program managers may not have the same access to information.

Regarding lesson two, information on necessary equipment, such as the lunar spacesuits and the crewed lunar lander, wasn’t publicly available until after CMSE’s announcement.[11] Technology readiness is usually a major factor in leaders’ willingness to make official announcements, so outside observers naturally looked for other signs in absence of confirmation from CMSE. However, technological developments take more effort to spot and when observing China, other signals are just as important. In China, aspirational statements indicate leadership intent. When official media repeats high level aspirations, local stakeholders can take action.[12]

For example, the CAS 40-year technology forecast was indeed aspirational, but more authoritative than originally expected. The People’s Daily in 2013 publicized CAS’s timeline with the headline, “CAS: China expects to achieve crewed Lunar landing and build a Lunar base around 2030.”[13] The People’s Daily article goes on to say that China’s lunar base will enable “crewed Mars voyages.”[14] This example illustrates that an organization like CAS can represent top leadership intent and steer technology developers at national and local levels in the leader’s desired direction.

The major lesson learned is that repeated statements of aspiration matter. If outside observers wait to confirm technology readiness, they may discount other important signals and fail to examine the relationship between key SOE and CNSA stakeholders and the CCP.[15] ,

Why does China aspire to conduct crewed Mars exploration by 2050?

China’s domestic drivers are just as important, if not more important, than external drivers for its ambition for a crewed Mars mission by 2050. Many signs indicate that the CCP intends a crewed Mars mission as one of many steps to symbolically and materially support China’s second centennial goal of achieving national rejuvenation at the 100th anniversary of the founding of the PRC in 2049.[16] In general, Chinese leaders often use space missions to celebrate key events.[17]

In particular, China’s first centennial for the 100th anniversary of the CCP was in 2021 and they celebrated with the successful landing of the robotic Tianwen-1 Mars rover. The CCP’s 100th anniversary was on July 1, 2021; Tianwen-1 entered Mars orbit in February and successfully landed in May.[18] Xi Jinping’s congratulatory message said, “On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the CCP, the Tianwen-1 mission successfully landed…”[19]

| For China’s second centennial, Xi Jinping expects “national rejuvenation” by 2049. Space plays an important role in China’s plan for national rejuvenation and a global first such as a crewed mission to Mars would be worth celebrating. |

More broadly, Chinese leaders marked the first centennial with achieving what they called “a moderately prosperous society,” which included both economic and social components.[20] Even in this regard, the Chinese space sector played a role. The opening of China’s commercial space sector in 2014 was part of a slew of policy shifts to widen the social benefits of national strategic industries towards achieving the first centennial goal.[21] Since then, China has continued to expand the benefits of the space industrial base for the crewed space program and deep space exploration across provinces beyond national level organizations.[22] This diversification of Chinese organizations and localities contributing to space technologies makes identifying key developments more complex for outside observers.

For China’s second centennial, Xi Jinping expects “national rejuvenation” by 2049.[23] Space plays an important role in China’s plan for national rejuvenation and a global first such as a crewed mission to Mars would be worth celebrating. For example, Xi Jinping recently said, “the spirit of space exploration can further enhance the national confidence and pride of the Chinese people…and [enhance] realizing national rejuvenation.”[24] Apart from the symbolism and national pride, the CCP also intends China’s space program to materially contribute to the second centennial goal through spurring innovation. Xi Jinping in a 2017 speech said that by 2035 China will become a global leader in innovation.[25] And in particular, a widely cited Chinese space industry report stated that by 2045 China will take the lead in select space technology areas.[26]

From the Chinese perspective, the domestic drivers for the completion of a crewed Mars mission by 2049 are just as strong, if not stronger, than the external drivers. That said, achieving a global first for its crewed space program would also cement China’s position as a top global space leader, equal to the United States. Competition with the United States is just one aspect of the external drivers. Just as important, leading global space exploration would allow the CCP to demonstrate that China has met its second centennial goal to become “a global leader in terms of composite national strength and international influence” and “a proud and active member of the community of nations.”[27] A link between China’s national rejuvenation and international influence implies that China will continue to find ways for international participation in its space program, likely to include the missions to Mars.

How committed is China’s government to crewed Mars exploration by 2050?

Applying lessons learned, both the authoritative CMSE and informed SOE representatives have already openly discussed that China is planning a crewed Mars mission. For example, in an interview at the annual National People’s Congress in 2018 the CMSE Chief Designer Zhang Baoan said the technology for a crewed mission to the Moon can be used to ferry a crew around Mars.[28] The CMSE website published Chief Engineer Zhou Jianping’s statements in 2021 and 2022 that, “We will aim for Mars.”[29] Even more telling, Chinese official media quoted China’s first taikonaut Yang Liwei in 2022 saying that, “China’s manned space program will go deeper into space…and there will be crewed exploration of Mars.”[30] If space watchers follow the same logic as in the lunar case, these statements should confirm Chinese leaders’ intent.

Apart from intent, SOE and CNSA representatives are again leading messaging of possible timelines for a Chinese crewed Mars mission around 2050. For example, as early as 2015, one of the same SOE representatives, Long Lehao, said that the earliest possible crewed Mars mission would be 2035.[31] A different SOE leader, Wang Xiaojun, in 2020 and at the 2021 Global Space Exploration (GLEX) Conference also stated that the earliest date for a crewed mission was around 2035.[32]

Even CNSA representatives are publicizing China’s crewed Mars mission at international forums. CNSA’s 2023 and 2024 presentations at the UN Committee of Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) depicted a crewed deep space orbiting vehicle around 2040.[33] Representatives from China’s new Deep Space Exploration Lab (DSEL) showed the crewed vehicle returning atmospheric samples from Venus in 2033 and a Mars research base in 2038.[34] This may very well foreshadow that “around 2050” is shifting to “by 2050.”

|

SOE and CNSA messaging is also focused on domestic audiences, which strengthens the likelihood that these timelines are sincere projections. In 2019 and 2022 interviews, key CNSA officials discussed how lunar technology linchpins like the new crewed orbiting vehicle will also be used for crewed Mars missions.[35] For example, in 2019 the CNSA website published an interview with the ShenZhou spacecraft’s Chief Designer, Qi Fayun, who said that “China will go to the Moon and Mars….so [we] need a new crewed vehicle.”[36] Representatives from China’s new Deep Space Exploration Lab showed the earlier timeline for a deep space crewed vehicle first at a domestic conference.[37] Before SOE representative Wang Xiaojun made his presentation to the 2021 GLEX Conference in Russia, he made the presentation at a domestic conference in 2020.[38]

Mars launch windows and related Chinese research

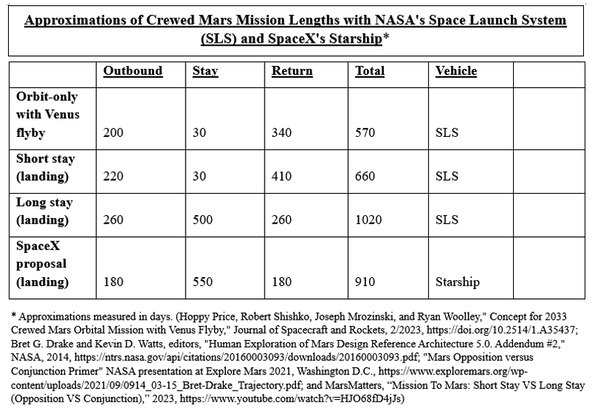

Physics primarily determines when a country can feasibly launch a crew to Mars. Mars and Earth are at the closest points in their orbits approximately every 26 months. Within the 26-month cycle, the best time to launch a crew may be during peak solar activity. While all radiation is a problem for the crew, it may be possible to shield against more severe solar activity. While at the same time, the increase in solar particles can limit the impact of other high energy particles coming from outside the solar system, which are more harmful.[39] The solar cycle peaks approximately every 11 years; a solar maximum is ongoing. Furthermore, the shapes of Earth and Mars’ orbits around the Sun create an additional benefit every 15–17 years when Mars is at its closest to the Sun. These beneficial launch conditions will overlap around 2033 and 2048 which would allow countries to launch large equipment with still shorter cruise timelines.[40] (See table)

Given these opportune launch windows, Chinese technical research unsurprisingly also considers both a general 2030s and a 2040s timeframe. Based on this report’s cursory search for Chinese analysis on an initial orbit-only crewed Mars mission, three different perspectives surfaced, each summarized below. Most of the reports also discussed a crewed Mars landing, but this report only highlights elements related to an orbit-only mission by 2050.

|

The first perspective is from technologists such as rocket and spacecraft designers, who need to provide the basic systems for transport. In 2014, researchers from a Shanghai municipal key lab and the SOE Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (SAST) outlined systems for a two person crewed launch in 2033 with a return around 2037, via Venus flyby.[41] They built off of a 2009 NASA study, and similarly proposed multiple launches to assemble and fuel payloads in Earth orbit.[42] The Shanghai team’s forecast assumed the rocket capabilities of the Long March 5 (LM-5) and, at that time, a yet-to-be-developed heavy launch vehicle in their proposal. Also assuming the LM-5, in 2015, the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics and the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT) showed the fuel needed to send a six-person crew to Mars, though they did not include details on the launch window.[43]

At a 2020 Chinese domestic conference and again in 2021 at the international GLEX conference in Russia, CALT representative Wang Xiaojun outlined a three-step plan. He proposed starting with robotic missions for site selection in 2033 and the first crewed orbit-only mission occurring around 2035.[44] Also in 2021, Wang Xiaojun and a colleague published a technical article which added more detail to the timeline he presented at GLEX, a timeline which relied on nuclear propulsion.[45] Their article described an ultimate crewed landing on Mars in the 2040s and did not expand on the orbit-only mission described briefly at GLEX. (Their paper described a mission that would include a 180- to 200-day transit both ways, and a 500-day surface stay, for a mission total of approximately 2.5 years using nuclear propulsion.) The paper also did not reference using a Venus flyby.

Other researchers at Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics in 2022 published an English article with a detailed proposal for a crewed launch in 2037 with return in 2040.[46] They specifically considered use of the Long March 9 (LM-9), which is China’s non-crew rated heavy launch vehicle that will also be used to launch modules to the Moon. (Readers should note that the author did not find Chinese researchers discussing the crew-rated Long March 10 (LM-10) in simulations for a Mars mission, which would be a necessary step.) Most recently, a Chinese presentation at another domestic conference described six LM-9 launches to low Mars orbit to assemble the “62.8 ton astronaut life support payload.”[47]

| If Chinese taikonauts beat US astronauts to Mars, how much impact will that have on the US-China competition for global influence? |

The second perspective which surfaced is regarding radiation and crew safety. Generally speaking, CMSE has actively publicized NASA’s radiation studies from the Martian surface and new methods of simulating galactic cosmic radiation to understand human health in deep space.[48] Additionally in 2021, Xinhua’s Science and Technology Division published a summary of a study from international and Chinese researchers recommending the mid-2030s for a crewed mission to Mars to co-occur with peak solar activity.[49] A Chinese-led study followed up with radiation data from Tianwen-1’s transit and similarly recommended crewed transit during solar maximum.[50] The Chinese-led study also made initial proposals for in-transit shielding during the more active solar eruptions from solar maximum.[51] CMSE’s own studies on radiation and human health are usually based on experiments at the Chinese Space Station (CSS). In one interview, however, Li Yinghui, the Director of the National Key Laboratory of Aerospace Medicine at CMSE’s Astronaut Research and Training Center generally discussed a crewed Mars mission saying that a “shorter transit time is better.”[52]

The third perspective is also related to crew safety, but in terms of navigation and communications. Researchers at the PLA National University of Defense Technology and SOE China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) in 2022 said that there is an “urgent need” to find a solution for enabling “autonomous navigation for a crewed Mars mission.”[53] The article’s findings were summarized on the CMSE website in 2023 saying that the researchers had determined an “autonomous navigation method to provide an effective guarantee for the implementation of China's crewed Mars exploration program in the future.”[54] Regarding the crew’s ability to communicate with Earth while in transit, Chinese experts tested a new crewed voice system on the CSS and said that it can be a reference case for crewed communications on Mars.[55] Chinese researchers from a Guangdong Province national key lab, the Harbin Institute of Technology, and an international researcher in 2024 proposed a multi-planet backbone relay system between China’s ground stations in the PRC and Argentina.[56] They showed how they could have at least the Mars, Venus, and Uranus links launched and interconnected for “a mission between January 1, 2040 to December 31, 2041,” but they did not specify it was for a crewed mission.

Milestones to watch

To support follow-on studies, this report focuses on an initial crewed orbit-only Mars mission. At a minimum, two technologies are necessary for an orbit-only mission. Watching for these will help space watchers assess China’s progress towards meeting its goal for a mission around 2050 and assessing the likelihood that the PRC could launch in the 2040s.

First, China’s LM-10 is the crew-rated rocket that will be used for both the lunar and Mars missions according to the official statements discussed above. China will first test launch the LM-10A, a single-stage version of the planned three-stage rocket, in 2026.[57] After that test, China will release a date for the test launch for the three-stage LM-10. The Chief Designer of the LM-10 is Zhang Zhi, who has published a technical report on key components of the LM-10, such as the engine, in 2022.[58] Zhang Zhi has not publicly discussed the role of LM-10 and the Mars mission, based on available information. However, in a 2019 Xinhua interview, he said that the LM-9 will enable a crewed Mars landing.[59] He was previously the LM-9 Chief Designer.[60]

The LM-10 is more important than the LM-9 for a crewed orbit-only mission. While Chinese state media in recent months continues to publish CALT representative Long Lehao’s statements that the LM-9 will be used for a crewed landing on Mars, readers need to remember that the LM-9 is not crewed rated.[61] The LM-9 would be used to launch the habitat modules for a crewed landing, which is outside the scope of this report. Crew-rated rockets undergo more testing and take more time.

China would also need its new crewed spaceship, MengZhou, for an orbit-only mission, presumably with modifications. The MengZhou Chief Designer, Ma Xiaobing, is not often in the media, and based on this review, he has not discussed Mars. According to state media and a rare article of Ma Xiaobing’s 2023 tour of companies engineering components for MengZhou, the spacecraft development is proceeding as planned.[62] A test flight to lunar orbit is the next step to watch.

Three questions to determine the implications for the US

There are three questions which US policymakers should consider when determining the implications of this research. The first is: If Chinese taikonauts beat US astronauts to Mars, how much impact will that have on the US-China competition for global influence? And a follow-on question would be: Is that the only impact? (Another way to ask the latter question is: How confidently can one link a crewed mission to Mars with achieving specific national priorities like the military’s ability to fight and win in next-generation warfare, or to significant technology spillovers in the US economy?)

If the answers to both questions are “yes,” it is important to recall China’s multipronged rationale. As discussed above, from China’s perspective, the domestic drivers are just as strong as the international drivers for its planned crewed exploration of Mars. The domestic drivers include not just important symbolism that China has achieved national rejuvenation, but the domestic drivers are also tied to economic goals intended to widen the benefits of the space industrial base.

The third question policymakers should consider is: Will SpaceX and other commercial companies seek Mars exploration cost-sharing and collaboration with China, if the US is not equally ambitious? Currently, US commercial companies’ plans for Mars are not completely contingent on a US government customer. Will that always be the case? Given the nascent international Mars probe data-sharing agreements, there is a basis for deepening international collaboration for future Mars exploration cost-sharing.[63]

Alternative analysis

As detailed above, there is ample evidence to suggest that a major space goal will play a role in the PRC’s celebration of its second centennial anniversary in 2049. Based on the research for this report, there are two alternative missions the PRC may pursue depending on how its domestic and international environment develop in the coming decade. A third, more cautious scenario, is also included to stimulate thinking on how international events could hypothetically delay the PRC.

- Crewed Mars landing by 2050. The Chinese technical papers mentioned in this report also discussed a crewed landing.[64] In addition to Chinese research on Mars habitat modules and spacesuits, it is clear that a crewed Mars landing is among the goals for China’s Mars program.[65] They are already messaging a Mars research station.[66] The question is, would China attempt a crewed landing before 2049?

- Crewed asteroid landing by 2050. In China’s 2010-era research on crewed missions to Mars, researchers also outlined a crewed mission to an asteroid for space resource utilization.[67] The crewed asteroid mission was likely their attempt to mirror NASA’s similarly stated ambitions, which may have also been deprioritized. China’s most recent reference to a crewed asteroid mission in a technical report was a 2024 paper about deep space transportation systems.[68] The capabilities China is developing for planned missions such as the robotic planetary defense mission, asteroid sample return mission, and mission to the outer edge of the solar system could potentially enable the PRC to shift to a crewed asteroid mission if desired.[69]

- High risk perception around 2050. The CCP wants to celebrate national rejuvenation, but not at the risk of embarrassment. While China regularly launches a crew to the CSS around its national holidays, China has not recently been involved in a major war or economic crisis. Without such an event, China space watchers have not seen instances where China has delayed its human spaceflight program. (CMSE has delayed launching the CSS telescope, but its delay is related to technology readiness and ongoing internal decisions about the role of the human spaceflight program in Earth observation and space science.) A much more thorough analysis is needed, but based on past Shenzhou launches to the CSS, there are some hiccups in the timeline that might be related to international security events. The longest time between launches was Shenzhou 11 (October 2016) and Shenzhou 12 (June 2021), which was separated by multiple North Korean intercontinental ballistic missile tests, particularly in 2017, some of which passed over Japan leading to additional United Nation sanctions.[70] The second longest spread was between the Shenzhou 6 (October 2005), Shenzhou 7 (September 2008), and Shenzhou 8 (October 2011), separated by China’s 2007 anti-satellite missile test and the United States’ 2008 Burnt Frost anti-satellite demonstration.[71]

Conclusion

There are ample authoritative signs that the PRC is progressing towards its goal to conduct an orbit-only crewed mission to Mars before 2050. In addition to authoritative statements from CMSE, which had been lacking in the crewed Lunar landing timeline, China’s other informed experts are again messaging a timeline that could result in a Chinese crewed Mars launch in the 2040s launch window. To determine the impact of Chinese taikonauts beating U.S. astronauts to Mars, this paper proposed analysts support policymakers by attempting measurable answers to three questions: 1. What would be the impact on the US-China competition for global influence?; 2. While there may be a perception of fading influence in the space sector, but is that the only impact?; and 3. If US commercial space companies stay committed to their ambitions for Mars, would that justify them in collaborating with other countries, even potentially China? Answers to those questions are beyond the scope of this paper. The main aim of this paper is to show that based on lessons learned, the PRC has already officially announced it will celebrate the founding of the PRC with a crewed Mars mission.

Endnotes

- Huadong Guo, Ji Wu, “Space Science & Technology in China: A Roadmap to 2050,” Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2010, and人民网 (People’s Daily), “中科院:中国预计在2030年前后实现载人登月建月球基地,” (Chinese Academy of Sciences: China is expected to achieve a manned landing on the moon and build a lunar base around 2030), 12/2/2013,

- Zhao Lei, “China aims to make manned moon landing before 2030,” China Daily, 5/30/2023.

- Burke, Kristin, “How to Assess the PRC’s Crewed Mars Mission Timeline”, 5/2024.

- Burke, Kristin, “How to Assess the PRC’s Crewed Mars Mission Timeline”, 5/2024.

- Michael Wilner, “Racing to the moon and Mars, U.S. intelligence sees China advancing with remarkable speed,” McClatchyDC, original 2023, updated 1/16/2015.

- 中国教育和科研计算机网网络中心 (China Education and Scientific Research Computer Network Network Center), “中国2025年前后可实现载人登月,”( China will be able to land a manned person on the moon around 2025), 7/12/2010, and 新浪 (Sina), “中国载人登月着陆点可能选择月球南极,” (China's manned lunar landing site may choose the south), 11/7/2010.

- 人民网 (People’s Daily), “龙乐豪院士在抖音开讲 分享中国航天发展历程与最新进展,” (Academician Long Lehao gave a lecture on Douyin to share the development process and latest progress of China's aerospace industry), 7/15/2022, and Andrew Jones, “Chinese crewed moon landing possible by 2030, says senior space figure,” SpaceNews, 11/15/2021.

- Marsha Freeman, “Systems and Infrastructure Needed to Enable A Chinese Crewed Lunar Landing,” U.S. Air Force China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), 7/2022, and Zhao Lei, “China aims to make manned moon landing before 2030,” China Daily, 5/30/2023.

- 中国新闻网 (China News Network), “中国在载人登月方面未来有何规划?国家航天局回应,” (What are China's future plans for a manned landing on the moon? The China National Space Administration responded), 12/17/2020.

- Michael Wilner, “Racing to the moon and Mars, U.S. intelligence sees China advancing with remarkable speed,” McClatchyDC, original 2023, updated 1/16/2015, and Kristin Burke, “Understanding China’s Space Leading Small Groups—The Best Way to Determine the PLA’s Influence,” U.S. Air Force China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), 7/2022.

- Marsha Freeman, “Systems and Infrastructure Needed to Enable A Chinese Crewed Lunar Landing,” U.S. Air Force China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), 7/2022, and Zhao Lei, “China aims to make manned moon landing before 2030,” China Daily, 5/30/2023.

- Anna L. Ahlers, “Chapter 10: Technocracy on the ground: cadre competence, expert involvement, and scientific advice in China's local governance,” Handbook on Local Governance in China, edited by Ceren Ergenc and David S.G. Goodman, 9/2023.

- 人民日报 (People’s Daily), “中科院:中国预计在2030年前后实现载人登月建月球基地,” (Chinese Academy of Sciences: China is expected to achieve a manned landing on the moon and build a lunar base around 2030), 12/2/2013.

- 人民日报 (People’s Daily), “中科院:中国预计在2030年前后实现载人登月建月球基地,” (Chinese Academy of Sciences: China is expected to achieve a manned landing on the moon and build a lunar base around 2030), 12/2/2013.

- Kristin Burke, “Understanding China’s Space Leading Small Groups— The Best Way to Determine the PLA’s Influence,” 7/2022.

- People’s Republic of China, “Achieving Rejuvenation Is the Dream of the Chinese People,” Xi Jinping speech, 11/29/2012.

- Kevin Pollpeter, Timothy Ditter, Anthony Miller and Brian Waidelich, “China’s Space Narrative,” U.S. Air Force China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), 2020.

- China National Space Administration, “Tianwen-1: China successfully launches probe in first Mars mission,” 7/23/2020, and China National Space Administration, “China shows first high-def pictures of Mars taken by Tianwen-1,” 3/4/2021.

- 人民日报 (People’s Daily), “习近平代表党中央、国务院和中央军委祝贺我国首次火星探测任务天问一号探测器成功着陆火星的贺电,” (Xi Jinping, on behalf of the CPC Central Committee, the State Council and the Central Military Commission, sent a congratulatory message congratulating China's first Mars exploration mission, the Tianwen-1 probe, on its successful landing on Mars), 5/15/2021.

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “Xi declares China a moderately prosperous society in all respects,” 7/1/2021.

- 付毅飞, (Fu Yifei), “盘点中国航天“十三五”:商业航天发展稳步推进,” (Taking stock of China's aerospace "13th Five-Year Plan": the development of commercial aerospace has been steadily advancing), 央视网 (CCTV), 9/28/2020, and 吉林省发展和改革委员会 (Jilin Province NDRC), “吉林一号”:亮出“白金名片,” ("Jilin No. 1": Show the "platinum business card"), 10/14/2017.

- 中国航天局, (China National Space Administration), “安徽聚力发展航天和空天信息产业 加快科技强省建设纪实,” (Anhui has made concerted efforts to develop the aerospace and aerospace information industries and accelerated the construction of a strong province in science and technology), 5/5/2023; 湖北省发展和改革委员会.(Hubei Provincial Development and Reform Commission), “聚焦“箭、星、网、端”一体发力 全力打造商业航天星箭制造产业集群”, (Focus on the integration of "arrows, satellites, networks, and terminals" to build a commercial aerospace star and arrow manufacturing industry cluster), 11/27/2024; 山东省人民政府办公厅, (General Office of Shandong Provincial People's Government), “山东省人民政府办公厅关于印发山东省航空航天产业发展规划的通知”, (Notice of the General Office of the People's Government of Shandong Province on Printing and Distributing the Development Plan of the Aerospace Industry in Shandong Province), 3/1/2024; Burke, Kristin, “Trends That Impact Perceptions of the Chinese Space Program,” U.S. Air Force China Aerospace Studies Institute, 8/2023; and Jones, Andrew, “China embraces commercial participation in moon mission for the first time,” SpaceNews, 1/27/2025, and Jones, Andrew, “China invites bids for lunar satellite to support crewed moon landing missions,” 2/14/2025.

- People’s Republic of China, “Achieving Rejuvenation Is the Dream of the Chinese People,” Xi Jinping speech, 11/29/2012.

- The National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, “Xi calls for accelerating progress in China's space endeavors,” 9/24/2024.

- The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, “Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” (2017 updated 2021), and U.S.-China Security and Economic Commission Annual Report, “Section 1: The Chinese Communist Party's Ambitions and Challenges at Its Centennial,” 11/2021.

- U.S. Office of the Director for National Intelligence, “Chinese Space Activities Will Increasingly Challenge US Interests Through 2030,” 4/2021, and 人民日报 (People’s Daily), “我国发布未来航天运输系统路线图,” (China released a roadmap for the future space transportation system), 11/17/2017.

- The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, “Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” (2017 updated 2021), and U.S.-China Security and Economic Commission Annual Report, “Section 1: The Chinese Communist Party's Ambitions and Challenges at Its Centennial,” 11/2021.

- 经济日报 (Economic Daily), “张柏楠代表:下一代载人飞船可登月探火,” (Deputy Zhang Bonan: The next generation of manned spacecraft can land on the moon and explore fire), 3/19/2018

- 中国载人航天工程网 (China Manned Space Engineering Network), “面对面 | 总结经验,直面挑战,周建平总师展望中国载人航天新征程,” (Face to face | Summing up experience and facing challenges, Chief Engineer Zhou Jianping looked forward to the new journey of China's manned spaceflight), 10/25/2021, and 航天员杂志QQ, (Astronaut Magazine on QQ), “两会航天声音|普通人进入中国空间站,神舟飞船可用于太空旅行,火星采样任务…,” (Ordinary people enter the Chinese space station, and the ShenZhou spacecraft can be used for space travel and Mars sampling missions), 3/11/2022

- 中国青年报 (China Youth Daily), “飞天圆梦三十载,中国走向更远深空,” (Thirty years after the dream of flying into the sky, China has gone further into deep space), 11/29/2022, and 人民网 (People’s Daily), “航天新征程|杨利伟:中国人将走向更远的深空,” (Yang Liwei: Chinese will go farther into deep space), 11/25/2022.

- 新华 (Xinhua), “不是科幻:中国星际穿越故事,” (Not Science Fiction: A Chinese Interstellar Story), 3/9/2015

- 澎湃新闻 (The Paper), “中国运载火箭技术研究院院长:未来载人火星探测构想分3步,” (President of the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology: The concept of future manned Mars exploration is divided into three step), 9/18/2020, and 中国航天报 (China Aerospace News on Weixin), “中国载人火星探测“三步走”设想,” (China's manned Mars exploration "three-step" concept), 6/2021,

- China National Space Administration, “China Space International Cooperation: Future Plans and Prospects,” UNOOSA, 6/2023, and China National Space Administration, “China’s Deep Space Exploration,” UNOOSA, 1/30/2024.

- China 航天 (China Aerospace), “中国最新发展路线图,” (China’s latest development roadmap…,) 微博 (Weibo), 3/25/2025

- 中国航天局 (China National Space Administration), “期待,中国深空探测“大动作”!” (Looking forward to China's deep space exploration "big move"!), 11/28/2022l

- 中国航天局, (China National Space Administration), “中国正研制新型可重复使用载人飞船瞄准月球火星,” (China is developing a new reusable manned spacecraft aimed at the moon and Mars), 9/12/2019

- China 航天 (China Aerospace), “中国最新发展路线图,” (China’s latest development roadmap) 微博 (Weibo), 3/25/2025

- 澎湃新闻 (The Paper), “中国运载火箭技术研究院院长:未来载人火星探测构想分3步,” (President of the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology: The concept of future manned Mars exploration is divided into three step), 9/18/2020, and 中国航天报 (China Aerospace News on Weixin), “中国载人火星探测“三步走”设想,” (China's manned Mars exploration "three-step" concept), 6/2021

- Lora Bailey, et al, “A Lean, Fast Mars Round-trip Mission Architecture: Using Current Technologies for a Human Mission in the 2030s,” NASA JSC, 2014, and Dobynde, Shprits, et al, “Beating 1 Sievert: Optimal Radiation Shielding of Astronauts on a Mission to Mars,” Space Weather, 8/2021, 10.1029/2021SW002749

- Guzek, B., Horton, J., and Joyner, R., “Analyzing Mission Opportunities for Earth to Mars Roundtrip Missions,” 42nd AAS Annual Guidance and Control Conference, 2019

- 王小军 and 汪小卫, (Wang Xiaojun and Wang Xiaowei), “载人火星探测任务构架及其航天运输系统研究,” (Research on the manned Mars exploration mission architecture and its space transportation system), 7/2021, and 朱新波,谢华,徐亮,and 陆希 (Zhu Xinbo, Xie Hua, Xu Liang, and Lu Xi), “载人火星探测任务方案构想,” (Configuration of Manned Mars Exploration Mission), 上海航天, (Aerospace Shanghai), 1/2014, 1006—1630(2014)01—0022—07

- Drake, Hoffman and Beaty, “Human Exploration of Mars Design Reference Architecture 5.0,” National Aeronautics and Space Administration , 7/2009

- 高朝辉, 童科伟, 时剑波, 申麟 (GAO Zhaohui, TONG Kewei, SHI Jianbo, SHEN Lin), "载人火星和小行星探测任务初步分析," (Analysis of the Manned Mars and Asteroid Missions), 2015

- 中国航天报 (China Aerospace News), “中国载人火星探测“三步走”设想,” (China's manned Mars exploration "three-step" concept), 6/2021; 赵挪亚 (Zhao Nuoya), “载人登陆火星三步走,中国科学家打算这么干,” (The manned landing on Mars is a three-step process, and Chinese scientists plan to do just that), 观察者网 (Observer), 6/26/2021; and 张静 (Zhang Jing), “中国运载火箭技术研究院院长:未来载人火星探测构想分3步,” 澎湃新闻 (The Paper) 9/18/2020, https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_9244413

- 王小军 and 汪小卫, (Wang Xiaojun and Wang Xiaowei), “载人火星探测任务构架及其航天运输系统研究,” (Research on the manned Mars exploration mission architecture and its space transportation system), 7/2021, and 朱新波,谢华,徐亮,and 陆希 (Zhu Xinbo, Xie Hua, Xu Liang, and Lu Xi), “载人火星探测任务方案构想,” (Configuration of Manned Mars Exploration Mission), 上海航天, (Aerospace Shanghai), 1/2014, 1006—1630(2014)01—0022—07

- Diyang Shen, Yuxian Yue and Xiaohui Wang, “Manned Mars Mission Analysis Using Mission Architecture Matrix Method,” Aerospace, 2022,

- China 航天 (China Aerospace), “我国载人火星探测设想,” (My country's manned Mars exploration concept..), 微博 (Weibo), 4/11/2025

- 中国载人航天工程网 (China Manned Space Engineering Network), “载人火星任务带电粒子辐射探测方案与应用技术研究,” (Research on charged particle radiation detection scheme and application technology of manned Mars mission), 10/22/2018, and 中国载人航天工程网 (China Manned Space Engineering Network), “NASA模拟宇宙射线研究对航天员健康的影响,” (NASA simulates the effects of cosmic ray research on astronauts' health), 7/20/2020

- 国家自然科学基金委员会 (National Natural Science Foundation of China), “本世纪30年代中期,载人登陆火星时机最佳” (In the mid-30s of this century, the best time for a manned landing on Mars was possible), 新华 科技日报 (Science and Technology Daily), 9/15/2021, and M. I. Dobynde, et. al., “Beating 1 Sievert: Optimal Radiation Shielding of Astronauts on a Mission to Mars,” Space Weather, 8/5/2021, 10.1029/2021SW002749

- Jingnan Guo, et. al., “Radiation environment for future human exploration on the surface of Mars: the current understanding based on MSL/RAD dose measurements,” Astron Astrophys Review, 9/20/2021, and M. I. Dobynde, et. al., “Beating 1 Sievert: Optimal Radiation Shielding of Astronauts on a Mission to Mars,” Space Weather, 8/5/2021, 10.1029/2021SW002749

- Jingnan Guo, et. al., “Radiation environment for future human exploration on the surface of Mars: the current understanding based on MSL/RAD dose measurements,” Astron Astrophys Review, 9/20/2021, and M. I. Dobynde, et. al., “Beating 1 Sievert: Optimal Radiation Shielding of Astronauts on a Mission to Mars,” Space Weather, 8/5/2021, 10.1029/2021SW002749

- 北青网, (Beiqing Net), “航天医学成果有哪些 如何走向深空探测?第一届航天医学前沿论坛在京举行,” (What are the achievements of aerospace medicine? How to move towards deep space exploration? The first Aerospace Medicine Frontier Forum was held in Beijing), 9/22/2023

- 中国载人航天工程网 (CMSE), “脉冲星导航在载人火星探测中的应用,” (Application of pulsar navigation in manned Mars exploration), 2/27/2023

- 中国载人航天工程网 (CMSE), “脉冲星导航在载人火星探测中的应用,” (Application of pulsar navigation in manned Mars exploration), 2/27/2023

- Yusheng Yi, et al, “Design of manned spacecraft voice communication system based on multi-terminal and multi-link,” International Conference on Communications and Broadband Networking, 10/2024/li>

- Jun Cao, Jian Jiao, Hao Liu, Rongxing Lu, and Qinyu Zhang, “Two-layer Lagrange-based relay network topology and trajectory design for solar system explorations,” 6/2024

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China's manned lunar exploration program under steady progress,” 3/3/2025; China Daily, “China aims for more ambitious space missions in 2025,” 1/16/2025; and Andrew Jones, “China’s new rocket for crew and moon to launch in 2026,” SpaceNews, 11/6/2024

- 中国载人航天 (CMSE), “新一代载人登月运载火箭总体方案和关键技术,” (The overall plan and key technologies of the new generation of manned lunar launch vehicles),2/21/2023, and 灰机wiki (HuiJi Wiki), “YF-75E,” 2025

- 新华 (Xinhua), “长七、长九、长十一……新一代运载火箭将助力中国航天走得更远,” (Long seven, long nine, long eleven...... The new generation of launch vehicles will help China's space industry go further), 5/16/2019

- Wikipedia, “长征九号运载火箭,” (LM-9), 2018

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China's new-generation Long March rockets to facilitate manned lunar, Mars missions,” 12/6/2024, and China Daily, “China aims for more ambitious space missions in 2025,” 1/16/2025,

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China's new-generation Long March rockets to facilitate manned lunar, Mars missions,” 12/6/2024; China Daily, “China aims for more ambitious space missions in 2025,” 1/16/2025; and 航天新光 (Aerospace Newlight), “五院新一代载人飞船总师马晓兵一行到公司调研,” (Ma Xiaobing, chief engineer of the new generation of manned spacecraft of the Fifth Academy, and his party visited the company for investigation), 6/8/2023/li>

- Jeff Foust, “NASA exchanged data with China on Mars orbiters,” SpaceNews 3/20/2021; NASA, “NASA, UAE Mars Missions Agree to Share Science Data,” 4/12/2022; and European Space Agency, “International collaboration,” 2025

- 王小军 and 汪小卫, (Wang Xiaojun and Wang Xiaowei), “载人火星探测任务构架及其航天运输系统研究,” (Research on the manned Mars exploration mission architecture and its space transportation system), 7/2021, and 朱新波,谢华,徐亮, and 陆希 (Zhu Xinbo, Xie Hua, Xu Liang, and Lu Xi), “载人火星探测任务方案构想,” (Configuration of Manned Mars Exploration Mission), 上海航天, (Aerospace Shanghai), 1/2014, 1006—1630(2014)01—0022—07 and Diyang Shen, Yuxian Yue and Xiaohui Wang, “Manned Mars Mission Analysis Using Mission Architecture Matrix Method,” Aerospace, 2022

- 赵建军, 甄文龙, 吕功煊, (Zhao Jianjun, Zhen Wenlong, Lv Gongxuan), “面向载人火星探测的CO2电解制氧技术发展现状与展望,” (Research Progress and Perspectives of Oxygen Production by CO2 Electrolysis for Manned Mars Exploration), 中国航天(Aerospace China), 2024 and Hongli Sun, Mengfan Duan, Yifan Wu, et.a., "Designing sustainable built environments for Mars habitation: Integrating innovations in architecture, systems, and human well-being," Nexus Review, 2024

- Andrew Jones, “China planetary roadmap for exploration,” X, 3/26/2025

- 高朝辉, 童科伟, 时剑波, 申麟 (GAO Zhaohui, TONG Kewei, SHI Jianbo, SHEN Lin), "载人火星和小行星探测任务初步分析," (Analysis of the Manned Mars and Asteroid Missions), 2015, and 张泽旭, 郑博, 周浩, 崔祜涛 (HANG Zexu, ZHENG Bo, ZHOU Hao, CUI Hutao), "载人小行星探测任务总体方案研究," (Overall Scheme of Manned Asteroid Exploration Mission), 2015

- 鲁宇,张烽, 汪小卫 (Lu Yu, Zhang Feng, Wang Xiaowei), "走向深空的航天运输系统," (Space Transportation Systems to Deep Space), 12/2024, 10.19963/j.cnki.2097-4302.2024.03.004

- Jeff Foust, “China reschedules planetary defense mission for 2027 launch,” SpaceNews, 7/16/2024; Andrew Jones, “China readies Tianwen-2 asteroid sample return spacecraft for launch,” SpaceNews, 2/20/2025; and Andrew Jones, “AI to power China’s mission to the edges of the solar system,” SpaceNews, 2/21/2025,.

- United States Mission to the United Nations, “FACT SHEET: Resolution 2371 (2017) Strengthening Sanctions on North Korea,” 2017, and Matt Stiles, “2017 was the year when North Korea became a threat to the U.S. mainland ,” Los Angeles Times, 12/28/2017

- Wikipedia, “ShenZhou Spacecraft,” and Dwayne A. Day, “Burning Frost, the view from the ground: shooting down a spy satellite in 2008”, 6/21/2021.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.