Strategies for lunar developmentby Jeff Foust

|

| “Governments change, budgets change. Is that really a reliable, sustainable model?” asked Davidson. |

Even if NASA did lead a lunar base, he said, how willing would other countries be to serve as “second-class citizens” in an outpost, he asked. On the other hand, a more commercial approach might lead to versions of company towns, he said, which has its own problems. “No one wants to live in a company town.”

The panel he was on was examining a different approach called the Lunar Development Cooperative, or LDC. The concept is the brainchild of Michael Castle-Miller, who has worked in international development projects known as “special jurisdictions,” like ports and trade zones, set up to stimulate economic growth in a region.

He got interested in the Moon six years ago attending another ISDC. “We started talking about a framework that would borrow some of the tools and things that I work on on Earth to support a lunar economy,” he said.

He and some others have spent the last several years fleshing out how those terrestrial approaches could be used on the Moon, which now take the form of the LDC concept. “The LDC will fund the development and public services for anyone operating on the Moon who becomes a member,” he said.

Membership would be open to both governments and companies, and those who join would have to agree to certain rules to support sustainable activities on the Moon. “We want to make the LDC humanity’s holding company for the Moon,” he said, with shares in it available to almost anyone.

One benefit of the LDC is financing for that lunar infrastructure. “This structure allows for blended financing,” he explained, an approach used on Earth for seaports and similar large infrastructure projects. “Sovereigns are lowering the risk for high-risk, high-cost infrastructure that doesn’t produce a return on investment for a long period of time. That unlocks a lot more private capital to be invested.”

The benefits of the LDC, they argue, go beyond financing. One thing the LDC would develop is a “site use register” where organizations who are members would record their planned uses of the Moon. Other members of the LDC would pledge not to interfere with those uses. Those rights could be marketable to other members, he added, effectively a form of property rights that gets around the prohibitions in the Outer Space Treaty to countries making territorial claims on the Moon.

Those who make those claims, though, would have to pay registration fees to the LDC that would become a primary source of income to the cooperative. “They’re not a tax,” Castle-Miller explained. “The fees will be based on the value of the rights they have in the LDC registry.” The value of the rights, he said, would be based on the demand for infrastructure the LDC would provide, like power and landing pads, needed for those uses. The fees would also ensure that the organizations registering potential uses will, in fact, implement them, rather than squatting on territory.

He envisions that would lead to a “virtuous cycle” where the LDC invests in infrastructure that is in demand for members, increasing the value of the registry and in turn the fees charged to members to support LDC operations.

But what about an organization—a company or a country—that doesn’t want to join the LDC? He argued if they tried to operate near LDC infrastructure, they would find themselves in constant conflict with LDC members as it tried to build its own infrastructure. (Or, he added, it could try to seize the LDC infrastructure, something that would lead to “major international backlash.”) More likely, he concluded, that entity would go elsewhere and be undisturbed.

| “We want to make the LDC humanity’s holding company for the Moon,” Castle-Miller said. |

While Castle-Miller and others have been working on the LDC concept for a few years, including a white paper on the concept, he acknowledged it is still in its early stages. “We’re not going to launch the LDC right away,” he said, focusing for now on research to lay the groundwork for it through stakeholder engagement and build support, and determining what infrastructure to develop first. “We’re between four and five years of this support building before we’re really ready to launch the LDC.”

The LDC is not the first concept for coordinating infrastructure development on the Moon. A study a decade ago for an “Evolvable Lunar Architecture” proposed an International Lunar Authority to oversee development, something that Davidson said was patterned on a port authority like the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which operates infrastructure ranging from bridges to airports.

“This is the weakest part of the ELA study,” he said of that governance concept. “If you lived in New York or New Jersey, you wouldn’t think this is such a great authority,” citing high tolls, crumbling infrastructure, and political bias.

“If I could do it over again,” he said of the earlier study, “I would pull out all that Lunar Authority stuff and put LDC in its place.”

Lunar markets

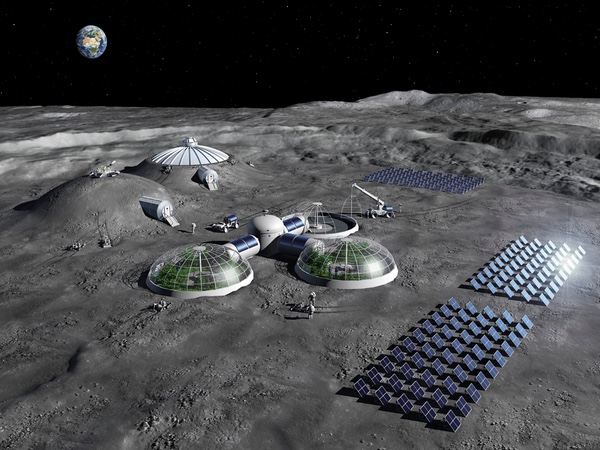

The LDC offers one approach to setting up infrastructure on the Moon to support government or commercial activities. A more fundamental question, though, is what people will be doing on the Moon to require that infrastructure.

In other sessions at ISDC, people took a skeptical approach to some proposed activities on the Moon. That included extracting helium-3, the isotope long associated with (as-yet undeveloped) fusion reactors but which has other applications, like quantum computing. Startups like Interlune have developed plans for robotic missions to prospect and, eventually, extract helium-3 from lunar regolith.

“I’ve been hearing about helium-3 on the Moon since the ’80s,” said Thomas Matula of Sul Ross State University. “But the world has changed since the ’80s.”

He noted helium-3 is far more abundant on Earth than previously thought. Meanwhile, the current market for heium-3 is $800 million annually. “It’s a small market that’s easily undercut by production from Earth,” he said, which he argued extends to other lunar mining concepts.

| “To me, the water at the south pole of the Moon is still at the level of a scientific curiosity. It’s not a resource yet,” Lee concluded. |

Water ice deposits in permanently shadowed craters at the south pole of the Moon could be another product, supporting lunar activities and potentially fueling other spacecraft. The problem, said Pascal Lee of the SETI Institute, is that water is in very low concentrations that would costly to extract: one cubic meter of regolith would yield just five liters of water.

“To me, the water at the south pole of the Moon is still at the level of a scientific curiosity. It’s not a resource yet,” he concluded. It would be technically feasible, but challenging, to extract it, putting its economic viability in doubt. “Meanwhile, a single Starship landing can bring 125 metric tons of water.”

That push for resources, he said, was putting the cart before the horse. “We have to bite the bullet of setting up an exploration and logistics base, not a mining operation up front.”

Another question is what will be taking place on the Moon that will require humans. “What are we going to do on the Moon that is of sufficient value to risk human life? It’s not clear to me right now that there’s anything like that other than geopolitical reasons,” said Rand Simberg.

“The only reason to have large numbers of people on the Moon is that people want to be on the Moon for whatever reason,” he concluded.

In those sessions, people identified other commercial markets at the Moon, such as providing commercial and navigation services. Matula suggested a Starship lander could deliver a large number of teleoperated rovers to the Moon, time on which could be sold to scientists or others. “How many people here would pay $1,000 an hour to run a rover on the Moon?”

The infrastructure needed for robotic rovers, research missions, and potentially small government bases is far different from sprawling outposts and mining installations. An LDC may be a solution to a problem that may not exist for decades, if ever.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.