Gemini’s wing and a prayer: Postscriptby Dwayne A. Day

|

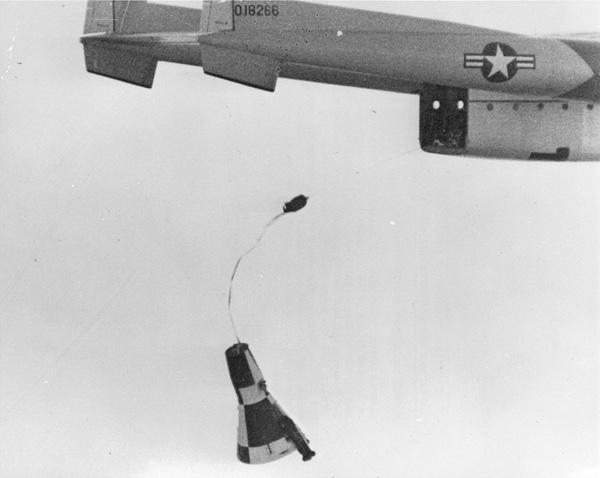

Drop test of a Gemini boilerplate vehicle in 1962 over west Texas. This vehicle was equipped with two solid rocket motors that fired three meters above the ground to cushion the impact. (credit: NASA) |

From catching spacecraft to dropping them

The Air Force’s 446th Airlift Wing, then the 446th Troop Carrier Wing, began working with NASA in October 1961. The unit was based out of Ellington Air Force Base, a short distance north from NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center (now known as Johnson Space Center). From 1961 to 1967, the 446th helped NASA test their Mercury and, later, Gemini spacecraft, by dropping boilerplates from the unit's C-119J "Flying Boxcars."

The C-119J was different from other C-119 models in that it was modified to catch reentry vehicles that had returned from orbit. Officially, this was part of the Air Force’s Discoverer program. But in reality, Discoverer was a cover story for the top secret CORONA reconnaissance program. As part of the 6594th Test Group, the C-119Js flew out of Hawaii to the northwest to perform their recoveries. But as one officer explained, the C-119 “was a two-engine plane in a four-engine ocean,” and in September 1961 the C-119Js were retired from this mission, replaced by much more capable C-130s. The C-119Js were then transferred to Ellington.

Gemini boilerplate vehicle in 1962 at Gary Air Field in Texas. This and similar tests explored alternative "soft" landing techniques for Mercury and later Gemini programs. (credit: NASA) |

At Ellington Field in Texas, the C-119J aircraft received adapted rear fuselages to drop boilerplate spacecraft from higher altitudes to test their parachute systems. In 1962, NASA conducted a series of drop tests of Gemini boilerplate vehicles equipped with parachutes and solid rocket motors that would fire just before the vehicle touched ground, an approach that was developed by the Soviet Union and is still used today with their Soyuz spacecraft.

This is most likely the El Kabong I boilerplate vehicle being loaded into a C-119J “Flying Boxcar” in 1965. El Kabong was used to test the parasail landing system. Although not adopted by the Gemini program, the parasail was considered for later space programs because it provided some controllability during descent. (credit: NASA) |

A later set of photographs, probably from 1965, appear to show the El Kabong I boilerplate that was used to test the parasail. The parasail was proposed for the “Big Gemini” spacecraft, and decades later it was proposed for the X-38 spacecraft. The El Kabong I boilerplate had recesses for its skid landing gear (as opposed to the Tow Test Vehicles 1 and 2, which had fixed landing gear.) The boilerplate also had a recess for two solid rocket motors that would fire before the vehicle touched down. These were angled forward and down, to halt the vehicle’s diagonal movement as it came down under the parasail. There was also a proposal to equip the Apollo Command Module with braking rockets. None of these proposals were extensively pursued. The drop tests were conducted over western Texas, and operating over land was much safer for the two-engine planes than the northern Pacific.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.