This spacecraft will self-destruct in 5, 4, 3, 2…by Dwayne A. Day

|

| What Albarracin had recovered, although no one knew it yet, was the forward satellite recovery vehicle (SRV) from CORONA reconnaissance mission 1005. |

Johnson’s concern about a CORONA vehicle in enemy hands wasn’t simply theoretical. In April, there was widespread concern that the second Discoverer satellite—which was the cover story for the CORONA program—had fallen on Spitsbergen Island in the Arctic. Air Force officers raced to the scene but did not locate the craft, and suspected that the Soviet Union might have retrieved it instead. This incident formed the basis for the novel and later movie Ice Station Zebra. There is no evidence the vehicle was recovered.

More to the point, a key Air Force official involved in the launch believed it was highly unlikely that the vehicle could have come down and hit the only bit of dry land amid millions of square kilometers of ocean. Discoverer 2 did not have a classified payload onboard, and the reentry vehicles were designed so that they would only float for 24 hours before sinking. But there was a real possibility that a future satellite, with exposed film showing Soviet targets, could be recovered by somebody other than the US government.

No self-destruct system was added to the reentry vehicles, but several future incidents probably made people involved in the program rethink that early decision.

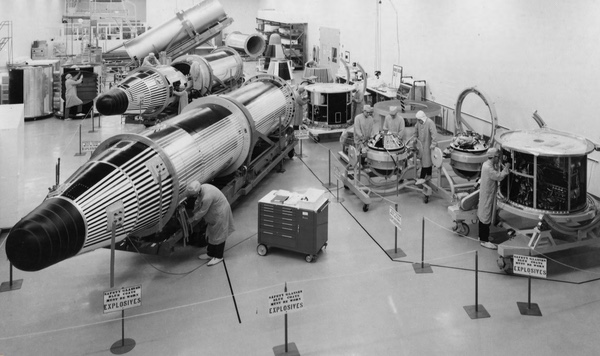

In 1964, a reentry vehicle from a CORONA reconnaissance satellite fell in Venezuela. Here a CORONA is being tested prior to shipment to the launch site in California. (credit: NRO) |

Falling star

Five years later, on Sunday, August 1, 1964, the phone rang on the desk of the US Army attaché at the United States Embassy in Caracas. The caller was a Venezuelan commercial photographer named Leonardo Davilla. He reported that what appeared to be part of a space vehicle had been found on July 7 on a farm in a remote rural region of the Andes Mountains near La Fria in Tachira State, near the Columbian border. Two farm workers had reported it to their employer, Facundo Albarracin, who had them move the object onto his own farm. News reached San Cristobal, where Davilla learned of it and traveled to see it. Davilla told the Army officer that the object carried markings that read “United States” and “Secret.” What Davilla did not mention to the Army officer was that he had photographed the object, and that Albarracin had been trying to sell it.

What Albarracin had recovered, although no one knew it yet, was the forward satellite recovery vehicle (SRV) from CORONA reconnaissance mission 1005.

Star-crossed mission

On April 27, 1964, a Thrust Augmented Thor Agena D rocket had lifted off from Vandenberg Air Force Base and arced to the south over the Pacific Ocean. Aboard was the fifth KH-4A CORONA reconnaissance satellite, with its J-1 camera. The KH-4A improved upon its predecessor the KH-4 by incorporating a second satellite recovery vehicle, more than doubling the amount of reconnaissance imagery produced by each mission. Each SRV contained a film-return “bucket”—so-called because it looked a lot like a steel kettle, with two spools of reconnaissance film.

The camera was programmed to turn on soon after the satellite reached orbit, operating intermittently for four days and filling up its first satellite recovery vehicle, which was then ejected over the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii for recovery. The SRV would be snatched out of the air by an aircraft and returned to the United States for processing. The satellite would then shut down for a week or more, operating in “zombie mode,” with electrical power and stabilization control gas closed off. One day before the camera was to be operated again, the spacecraft was reactivated. It would photograph more reconnaissance targets for another four-day period before the second SRV was ejected and recovered.

The launch of the April 1964 mission, labeled number 1005, was uneventful. But after 350 camera operations the film for the “slave” camera—the panoramic camera located in the forward part of the vehicle—broke. Shortly afterward, the Agena power supply failed. On April 30, ground controllers ordered the spacecraft to eject its first SRV for reentry on southbound revolution number 47. The vehicle verified receipt of the command but did not carry it out. Various ground stations repeatedly sent commands to the satellite on 26 subsequent passes through May 20. On May 19, the vehicle no longer acknowledged the receipt of the commands. Ground controllers assumed that the vehicle was headed for an uncontrolled reentry and would burn up, as had other spacecraft.

The US satellite tracking network kept close watch on the capsule. Early calculations of its decay rate led to a prediction that it would impact in the Pacific, west of the coast of South America and about 10 degrees north of the South Pole—far from inhabited land. But later calculations based upon better orbital trace measurements indicated that the capsule would probably come down somewhere in Venezuela. Observation stations in the Caribbean were alerted to watch the skies on May 26, the anticipated date of reentry. At six minutes after midnight, on northbound orbit number 452, observers in Maracaibo, Venezuela, reported five bright objects passing overhead, heading for the South American coast and presumably the ocean. Nearly six weeks later, the two farm workers stumbled upon the wreckage.

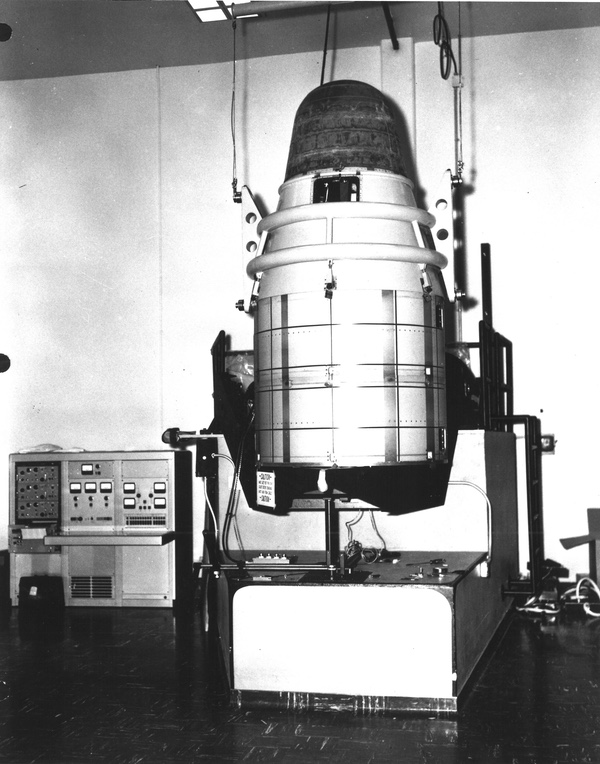

In 1964, the reentry vehicle from a CORONA reconnaissance satellite fell on a farm in Venezuela. Photographs of the vehicle appeared in at least one newspaper. The film rolls are visible inside the vehicle. (credit: NRO) |

The Venezuelan chase

When Leonardo Davilla called the US embassy on August 1 and spoke to the Army attaché, he apparently was not very convincing, because the Army officer initially did nothing. But Davilla called back on the following Monday. The Army attaché then called the embassy’s Air attaché to notify him of what Davilla had said. The two officers were unable to find an aircraft to take them to Facundo Albarracin’s farm. On Tuesday they interviewed a commercial pilot who had seen the object and had returned to Caracas with a souvenir piece. The Army attaché flew to La Fria, the village nearest to where the object had reportedly been found. But when he arrived, he learned that the Venezuelan army had arrived first and had taken it to San Cristobal, the provincial capital. He then headed to San Cristobal, where he examined it himself.

| Apparently, the United States had to buy back its spacecraft from the Venezuelans, but not before the Minister of Defense apparently decided to keep the radio transmitter beacon as a souvenir. |

The capsule was not in good shape. It had been heavily damaged in the impact. Even worse, in the three weeks since it had been found, local farmers had hacked away at its skin. They had noticed a gold disc attached to the upper section of the capsule. This disc, made of real gold, was used as a heat dispersion mechanism during reentry. As this and other discs melted, they sheathed the capsule in foil-thick pure gold. The farmers had hacked at the vehicle looking for more of the discs. Various passerby had also removed pieces, and the farmer whose ranch the vehicle had landed on reportedly gave the strobe beacon light to one of his children as a toy. One farmer had used the parachute lines as a harness for his horse.

The Army attaché also found an American nickel and a quarter in the wreckage. On at least one previous mission coins had been found hidden inside a recovered reconnaissance capsule and the Air Force had issued an injunction against such practices. Obviously, the injunction was being ignored. In addition to the coins, the attaché reported finding the film that remained in the bucket. He described it as “well-cooked.”

The Venezuelan army ignored the American Army officer’s request to release the object to US authorities. The Venezuelan army, with the American in tow, flew the wreckage to Caracas and promised to deliver it to the Americans on the following day, Friday, August 6. But when the object reached Caracas, it was taken directly to the office of the Venezuelan Minister of Defense. It did not return to American hands until Tuesday, August 10. Apparently, the United States had to buy back its spacecraft from the Venezuelans, but not before the Minister of Defense apparently decided to keep the radio transmitter beacon as a souvenir.

The spooks arrive

By this time Air Force officers attached to the CIA had arrived in Caracas to retrieve the object. They reported that the impact and souvenir-hunters “have pretty well reduced internal equipment to junk.” The impact had compressed the capsule to about two-thirds of its original length. The spooled film was beyond salvage. Part of the ablator was missing, along with most of the parachute cover, the parachute (which had not deployed), the thrust cone, the rocket motor, and all but one of the gold discs.

By now many people knew about or had seen the top-secret equipment. But what was worse was that the story had spread beyond the people associated with the object’s recovery. On August 4, the local Reuters correspondent had reported the find in a dispatch that was picked up by several wire services. The story appeared in the Washington Star and the New York Times on August 5, before the capsule was even back in American hands. Photos appeared in the San Cristobal newspaper, Diario Catolico, clearly showing the film-takeup reels inside the battered capsule. One reel was full, the other nearly empty. To a trained eye, these would be rather obvious indicators of the presence of a camera.

In classic understatement, the Director of the National Reconnaissance Office wrote that the experience “provided valuable engineering data on non-optimum re-entry survivability.”

If the efforts to retrieve the capsule in Venezuela had been somewhat comical, the comedy was not about to end. The recovered capsule was shipped to Lockheed’s Advanced Projects facility in Palo Alto, California via a “secure air route,” probably involving one of the CIA’s murky airline operations.

But this was not sufficient for the spooks, who also created a dummy package that they would ship via normal military transportation back to the United States. The dummy package was a crate filled with paper, pieces of wood, and scrap metal. It was addressed for shipment to the home of a Defense Intelligence Agency officer assigned to the Pentagon. But the shipping manifest declared that the cargo weighed 113 kilograms (250 pounds) when it actually weighed only 36 kilograms (80 pounds). When the cargo reached McGuire Air Force Base the weight discrepancy was noticed by customs officials, who assumed that they had intercepted a drug shipment. They opened the carton and found only the inexplicable junk, shipped at considerable expense back to the United States. They contacted the addressee and informed him that they were “going to investigate.” The officer stalled them and made a frantic call to the CIA to “cut this one off.” The CIA, through its contacts with the Customs Bureau, retrieved and destroyed the box six days later. Another, albeit minor, breach of security was averted.

The CORONA operations team evaluated the causes for the Agena and camera problems and attempted to fix them. When the battered capsule finally reached Lockheed in Palo Alto, it was carefully examined by the CORONA team. They recommended several changes pertaining to future reentry vehicles. First, all classification markings were removed from orbital CORONA vehicles before launch; objects clearly labeled “Secret” were likely to draw unwanted attention if recovered. Second, a new label was substituted offering, in eight languages, a “reward for return to American authorities” of the recovered part. Finally, vehicle inspection procedures were reinforced to protect against the stowage of more souvenirs during fabrication and checkout.

Six years later, another classified satellite fell on another farm.

A GAMBIT-3 satellite prior to launch at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. (credit: NRO) |

Charred debris in England

On May 20, 1972, the US Air Force launched a Titan III Agena D rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. This was GAMBIT mission 4435. Although this was a GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite, like the Air Force had launched 34 times before, it included several hardware changes from its predecessors, based upon lessons learned in GAMBIT and other programs. One such change was a Gemini Uniform Mixture Ratio engine installed in the secondary propulsion system. The GUMR engine could enable the rocket to lift an extra 90 kilograms (200 pounds) or change inclination. A Backup Stabilization System allowed the use of surplus gas in the primary control system, which could increase the number of times that the spacecraft could rotate its camera to either side of its ground track. The extra lift capacity allowed the spacecraft to carry heavier “magnum” model batteries, a total of ten. This increased the orbital lifetime to 30 days. Mission 4435 would be the longest-lasting GAMBIT mission to date.

Except it didn’t work out that way.

Despite the modifications, GAMBIT mission 4335 was doomed. A pneumatic regulator, used for delivering control gas to the Agena upper stage, failed to operate properly during the ascent. The Air Force tried to predict the impact point for the rocket, concluding that it was somewhere over South Africa. But probably because the reentry footprint was so big the Air Force did not attempt to search for it.

| That any debris reached the ground was a surprise to program officials, because at the time they had invested significant effort into determining how much material would survive reentry and their models indicated that everything should burn up. |

Three months later, Dr. Walter F. Leverton of the Aerospace Corporation, which provided engineering support to various classified and unclassified American intelligence and military space projects, was visiting his company’s London offices. While there he heard from a co-worker about some “interesting space material” that had been recovered in England earlier in the year. Leverton was interested in the story and arranged to visit the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough.

When Leverton arrived, the RAF people showed him some objects, including a spherical titanium pressure vessel a foot in diameter and some circuit boards that had US markings. But the most telling things he saw were several chunks of glass that could be assembled into a pie-shaped wedge with a 25-centimeter (10-inch) edge. This was no ordinary glass but was backed with a still-classified material manufactured by Eastman Kodak and characteristic of the optics used in the GAMBIT-3 satellite.

Leverton was informed that all the pieces had been found 120 kilometers (75 miles) north of London in an eight-kilometer (five-mile) radius where they had fallen on or around May 20, 1972.

Leverton realized that this was debris from a GAMBIT satellite and called his project office in California using private channels—probably a secure telephone—so that nobody else learned about the discovery. He arranged for the material to be transferred back to the United States. Later analysis confirmed that the debris was from mission 4335.

That any debris reached the ground was a surprise to program officials, because at the time they had invested significant effort into determining how much material would survive reentry and their models indicated that everything should burn up. The circuit boards and pieces of glass from mission 4335 proved that this was not the case. (See “Black Fire: De-orbiting spysats during the Cold War,” The Space Review, October 25, 2010.)

Spooky items

In the 1990s Sergei Khrushchev, the son of Nikita Khrushchev and himself a former Soviet aerospace engineer, claimed that in the 1960s the Soviet Union had retrieved parts from several American reconnaissance satellites and that in one case some film had been recovered by peasants who used it to cover their house. However, it seems far more likely that if any materials or film were recovered, they came from some of the hundreds of spy balloons that the United States had floated over the Soviet Union in the 1950s, most of which were shot down or fell somewhere in the vast Soviet arctic. None of them had self-destruct systems either.

According to Soviet space expert Bart Hendrickx, the Soviets equipped their Zenit and Yantar reconnaissance satellite reentry vehicles with self-destruct systems, and on several occasions the mechanisms were activated. He adds that the Orlets-1/Don reconnaissance satellites, which operated between 1989 and 2006, detonated in orbit at the end of their missions. The spacecraft blew up rather than de-orbiting. A more advanced version, launched only twice, in 1994 and 2000, de-orbited at the end of the mission.

There is no indication of a Soviet satellite falling on a non-Soviet farm.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.