The (possibly) great lunar lander raceby Jeff Foust

|

| “SpaceX has the contract. SpaceX is an amazing company. They do remarkable things, but they’re behind schedule,” Duffy said. “So, I’m in the process of opening that contract up.” |

After the dust settled from NASA’s selection in April 2021 of SpaceX’s Starship for the Human Landing System (HLS) program and subsequent GAO protest and lawsuit from losing bidders, NASA said it expected to use Starship on the Artemis 3 mission in 2025. That was already a delay from 2024 that the agency blamed on that extended litigation (see “Resetting Artemis”, The Space Review, November 15, 2021.)

That 2025 date subsequently slipped in large part because of delays in Artemis 2, pushed back from 2024 to now no earlier than February 2026 because of issues with Orion on Artemis 1 in 2022, including unexpected heat shield erosion. Assuming Artemis 2 keeps to something like its current schedule, NASA’s official schedules call for Artemis 3 some time in 2027.

Even if SLS and Orion are ready for Artemis 3 in 2027, there are growing doubts that Starship will be. A series of test-flight failures of Starship earlier this year pushed back the timeline for development of the vehicle, including key tests needed for the lander version. For example, NASA expected last year that SpaceX would perform tests this year of in-orbit propellant transfer, a critical technology needed to fuel Starship for its lunar mission. Those tests now won’t take place until some time in 2026.

At a Senate Commerce Committee hearing in September, former NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine—who led the agency when the HLS program started but left a few months before the selection of Starship—expressed skepticism about Starship’s readiness. Calling the overall landing architecture “extraordinarily complex,” he concluded that it was “highly unlikely that we will land on the Moon before China.” (See “Go faster, somehow,” The Space Review, September 8, 2025.)

Bridenstine was not alone in that assessment. Later in September, NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel offered its own blunt assessment of HLS. “The HLS schedule is significantly challenged and, in our estimation, could be years late for a 2027 Artemis 3 Moon landing,” concluded Paul Hill, a member of the panel, at its September 19 public hearing.

Hill was among the members of the panel who went to SpaceX’s Starbase facility in Texas in August, meeting with company executives. That visit informed his conclusion, which he said was based on the need to demonstrate in-space refueling as well as delays in development of version 3 of Starship, whose first flight is expected in the next couple of months.

Those concerns, though, appeared to be just the views of outsiders. That changed on October 20, when Sean Duffy, the secretary of transportation and acting NASA administrator, dropped a bomb on live television, in interviews on both CNBC and Fox News that morning.

“SpaceX has the contract. SpaceX is an amazing company. They do remarkable things, but they’re behind schedule,” he said on Fox. “So, I’m in the process of opening that contract up.”

“I’m going to let other space companies compete with SpaceX, like Blue Origin, and again, whatever one can get us there first, to the Moon, we’re going to take,” he said on CNBC.

He didn’t elaborate on what it meant to be “opening that contract up,” and it wasn’t until the end of the day that NASA provided any more details (a delay that may be due to the ongoing government shutdown that has furloughed most NASA employees, including public affairs staff.) NASA eventually stated that the agency had asked SpaceX and Blue Origin, which has its own HLS contract for Artemis 5, to provide “acceleration approaches” by October 29. NASA would also issue a request for information to allow other companies offer their own approaches.

There had been speculation in recent weeks that Blue Origin was pushing its own approach for an accelerated lunar landing. That would involve its smaller, uncrewed Blue Moon Mark 1 lander in addition to, or in place of, the larger crewed Mark 2 lander it is building for HLS. The company is completing its first Mark 1 lander, which Blue Origin plans to launch on its New Glenn rocket in the next several months.

During a panel discussion last week at the American Astronautical Society’s von Braun Space Exploration System, a company official hinted that was the case. “With Mark 1 and some of the preceding work we’re doing, we have what we think are some good ideas about maybe a more incremental approach that could be used for an acceleration-type scenario,” said Jacki Cortese, senior director of civil space at Blue Origin.

She declined to go into details about the plan, citing the competition-sensitive details of the work.

| “If the goal is to beat China to the Moon, we need to have a program that is, dare I say, a Defense Production Act kind of program,” Bridenstine said. |

Lockheed Martin, not currently part of the HLS program, has also shown an interest in offering alternative landers to NASA. In a statement hours after Duffy’s bombshell, Bob Behnken, vice president of exploration and technology strategy at Lockheed Martin Space, said his company had performed “significant technical and programmatic analysis for human lunar landers that would provide options to NASA for a safe solution to return humans to the Moon as quickly as possible.”

That approach would involve a two-stage lander with a descent element that remains on the surface and an ascent element that lifts off to return to Orion, said Tim Cichan, chief architect for commercial civil space at Lockheed Martin, on another panel at the symposium last week.

“The intent there is, let’s add another system that, from today, can move as fast as possible with as little risk as possible, using parts that actually exist right now,” he said. “That might be the fastest way.”

In his Senate testimony in September, Bridenstine didn’t offer an alternative to Starship for Artemis 3 even as he warned it would not be ready before China’s anticipated 2030 crewed lunar landing. Speaking at a Center for Strategic and International Studies event the day after Duffy’s announcement, he declined to weigh on the acting administrator’s proposal.

“I’m going to leave it to him to make those decisions,” he said of Duffy, noting the two were friends from their time in Congress together in the 2010s. “I certainly don’t want to opine about or second-guess what he’s got in front of him.”

Bridenstine, though, did weigh in at last week’s symposium. “Secretary Duffy, I think, is doing the absolute right thing,” he said, arguing that with the current architecture, “the probability of beating China approaches zero, rapidly. We have to do something different.”

He suggested something like a crash program to develop a lander. “If the goal is to beat China to the Moon, we need to have a program that is, dare I say, a Defense Production Act kind of program,” he said, citing Cold War-era law that allows the government to order companies to prioritize work on projects deemed critical to national security.

“We’re going all-in to build a landing system as quickly as possible with a team that would be a small team with authorities—maybe authorities put together by an executive order from the President of the United States—that this is a national security imperative that we’re going to beat China to the Moon,” he said, noting a “small Skunk Works-type organization” might be best to achieve that.

Bridenstine was speaking during a fireside chat that featured another former NASA administrator, Charlie Bolden. “At the risk of being repetitive, what Jim says is absolutely correct,” Bolden said after Bridenstine’s HLS comments.

“I did not recognize the architecture when I came back to thinking about NASA again after Jim had left office,” Bolden said. “Holy geez, how did we get back here where we now need 11 launches to get one crew to the Moon?”

“We cannot make it if we say we’ve got to do it by the end of this term,” he said. “Let’s be real, okay? Everybody in this room knows, to say we’re going to do it by the end of the term, or we’re going to do it before the Chinese, that doesn’t help industry.”

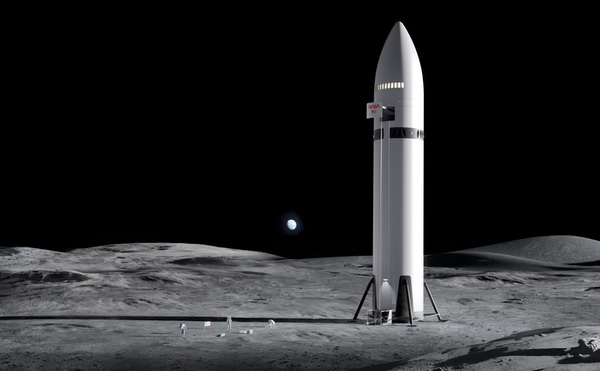

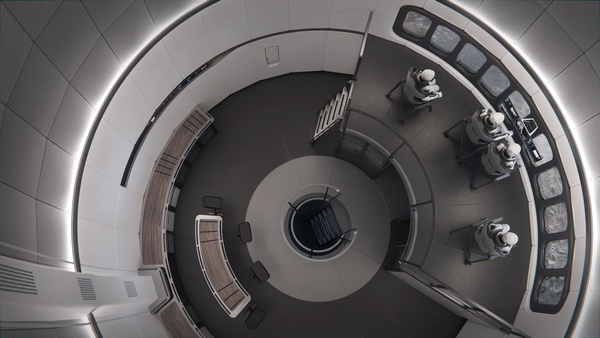

SpaceX released new details last week about its work on the Starship lander, including an illustration of what the crew cabin will look like (credit: SpaceX) |

SpaceX on the defensive

Duffy’s announcement, as well as the criticism from others in the field, has put SpaceX on the defensive. The company has reacted on a spectrum from offering technical details to derision.

| “SpaceX is moving like lightning compared to the rest of the space industry,” Musk stated, adding, “Starship will end up doing the whole Moon mission.” |

The latter came from SpaceX CEO Elon Musk immediately after Duffy’s TV appearances. He focused his criticism on Duffy himself, arguing he was not suited to lead NASA. He linked the comments to reports that Duffy was interested in incorporating NASA, an independent agency, into the Department of Transportation in some way.

“Sean Dummy is trying to kill NASA!” he said in one social media post, while in another insinuated that Duffy had an IQ of less than 100.

“SpaceX is moving like lightning compared to the rest of the space industry,” Musk stated, adding, “Starship will end up doing the whole Moon mission.”

On Thursday, SpaceX balanced that invective with information. The company posted a lengthy statement outlining the work it has done on the HLS version of Starship. “With the scale of Starship and the technological breakthroughs it is engineered to achieve, SpaceX is moving at a historically rapid pace,” the company argued.

It noted it had completed 49 milestones on its HLS contract, the “vast majority” of which were done on or ahead of schedule. (The company has not disclosed the number of milestones in the overall contract or its schedule.) Those milestones range from tests of Starship’s lander legs on simulated lunar regolith to demonstration of the Starship airlock and elevator astronauts will use to reach the lunar surface to life-support systems inside Starship.

SpaceX included with the announcement new renders of the interior of the Starship lander as well as images of ongoing test activities.

“Starship continues to simultaneously be the fastest path to returning humans to the surface of the Moon and a core enabler of the Artemis program’s goal to establish a permanent, sustainable presence on the lunar surface,” the company stated, but added that it had offered NASA an even faster path.

“In response to the latest calls, we’ve shared and are formally assessing a simplified mission architecture and concept of operations that we believe will result in a faster return to the Moon while simultaneously improving crew safety,” SpaceX stated.

It did not, though, disclose details about that simplified approach, including changes to Starship or other parts of the overall Artemis architecture. (There has been speculation SpaceX proposed an approach that would rely entirely on Starship and not use SLS or Orion, one that is unlikely to win support with NASA or on Capitol Hill.)

SpaceX, in that statement, confirmed that the in-space propellant transfer tests, which included studying how Starship operated for extended periods in orbit, would take place some time next year, but was not more specific. “The exact timing will be driven by how upcoming flight tests debuting the new Starship V3 architecture progress, but both of these tests are targeted to take place in 2026,” the company stated.

It also did not disclose its best estimate of when Starship would be ready for the Artemis 3 landing, which includes not just the propellant transfer demo but also an uncrewed lunar landing of Starship.

While SpaceX has provided more details about its approach, it has also not stopped attacking critics. The company took to social media Friday after several articles about Bridenstine’s comments at the von Braun symposium.

| “Starship continues to simultaneously be the fastest path to returning humans to the surface of the Moon and a core enabler of the Artemis program’s goal to establish a permanent, sustainable presence on the lunar surface,” SpaceX stated. |

“Mr. Bridenstine’s current campaign against Starship is either misguided or intentionally misleading,” SpaceX stated, noting that Bridenstine was in charge of NASA when it awarded HLS study contracts to SpaceX, among other companies. The company also noted that Bridenstine is now a lobbyist for companies in the space industry.

“Mr. Bridenstine’s recent musings promoting a new landing system – going so far as to invoke the Defense Production Act – are being misreported as though they were the unbiased thoughts of a former NASA Administrator. They are not,” SpaceX stated. “To be clear, he is a paid lobbyist. He is representing his clients’ interests, and his comments should be seen for what they are – a paid lobbyist’s effort to secure billions more in government funding for his clients who are already years late and billions of dollars overbudget.”

Bridenstine’s lobbying firm, The Artemis Group, works for many space companies, according to federal filings. By far the largest, in terms of payments, is United Launch Alliance, which spent more than $750,000 so far this year.

But ULA is largely on the sidelines of Artemis: it is neither developing a lunar lander nor has publicly announced that it is working with others on such plans. Most of the other companies that have paid Bridenstine are also not involved with Artemis or lunar landers in any significant way. One exception is Impulse Space, which announced last month its intent to develop a lunar lander; that would be for cargo, though, with payload performance similar to Blue Origin’s Blue Moon Mark 1 cargo lander.

“I founded The Artemis Group with the mission to ensure the United States remains the preeminent spacefaring nation. The statements I make, the clients we represent, and the policies we advocate for are guided by that mission,” Bridenstine said in a statement Friday.

“As I’ve stated numerous times, we need Starship to be successful and I’m very supportive of their efforts to return humans to the Moon,” he said.

Bridenstine has been supportive of Starship in general, in public presentations such as last week’s fireside chat. “Starship is a tremendously important vehicle for the future,” he said then. “It’s going to deliver large mass to low Earth orbit for a long time, and it’s going to drive down costs and increase access.”

“But if you need a Moon lander, it’s going to take time,” he added.

How much time, at least beyond that that notional 2027 date for Artemis 3, is still unclear, as well as if there really is any faster option to return humans to the Moon, using Starship or another vehicle.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.