State-owned enterprises and commercial space in Chinaby Owen Chbani

|

| China’s experiment with commercial space activities began in 1986 as a way to sell launches to foreign and domestic customers. |

Since the 2014 Document 60, which opened the space sector to private investment, China has seen an explosion of private space enterprises alongside the large SOEs. This paper aims to explore the evolving role of SOEs in China’s space ecosystem and argue that SOEs have been critical to the formation of the nascent commercial space sector. Chinese SOEs contribute to the success of commercial space firms through: (1) talent attraction and centralization acting as “hubs” that commercial firms cluster around; (2) conducting fundamental and applied R&D; and (3) providing financing and technology to commercial firms.

Major SOEs in the Space Sector

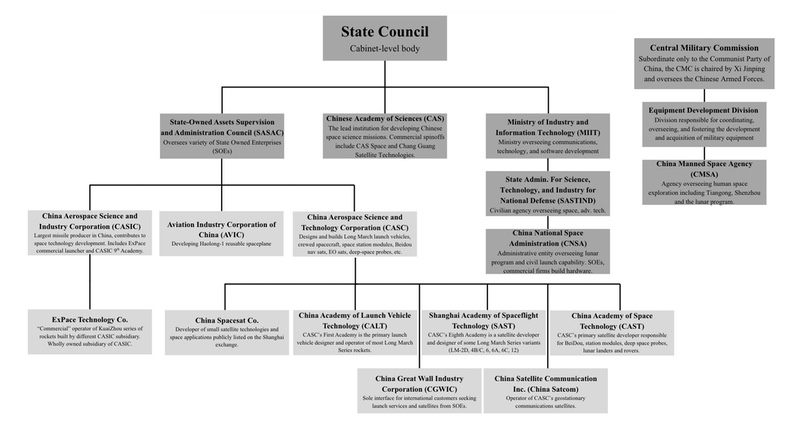

Although China has more than 150,000 SOEs, only 96 are administered directly by the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Council (SASAC).[2] The two primary “space” SOEs, China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC), employ hundreds of thousands of employees between them, with dozens of subsidiaries.[3,4] CASC retains the majority of space technology capabilities, responsible for implementing the Tiangong program, the lunar program, as well as most of the Long March vehicles. CASIC is primarily a defense contractor, responsible for developing missiles for the PLA, but retains experience in solid launch vehicles, anti-satellite weapons, microsatellites, and electronics.[5] Other SOEs participate in space activities but do not lead major programs.

Unlike the United States, where most civil space exploration is centralized at NASA, China has a trilateral structure with the Chinese National Space Agency (CNSA), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), and China Manned Spaceflight Agency (CMSA). The CMSA reports to the Central Military Commission (CMC), unlike the civilian State Council, which the CNSA reports to. While the CNSA oversees most civil space efforts, the CAS sets its own priorities and develops science missions independently. The CMSA develops, operates, and oversees China’s human spaceflight programs, including Tiangong, Shenzhou, and the lunar program. All three work closely with SOEs to develop much of the hardware needed.

Figure 1: Selected Chinese state-owned and governmental space organizations[6] |

Commercial space in China 1986–2014

China’s experiment with commercial space activities began in 1986 as a way to sell launches to foreign and domestic customers through the China Great Wall Industries Corporation (GWIC)—a subsidiary of CASC—at a time when global launch capacity was constrained post-Challenger.[7] The success of this effort was immediately apparent, with China launching 27 satellites by 2000, bringing in billions in foreign currency.[8]

Chinese SOEs pursued joint ventures with foreign companies as part of a strategy to attain foreign technology in exchange for access to Chinese markets. In one instance, Chinese SOEs, including CASC and CAST, formed China Galileo Industries to partner with the EU on the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) constellation Galileo. China Galileo Industries participated in the transfer of critical GNSS technologies, including atomic clocks, to China. When it became clear that China was pursuing an independent BeiDou GNSS constellation, the relationship quickly fell apart.[9] In the 2000s, Chinese SOEs exported 17 satellites as “turnkey” solutions to developing nations through GWIC; GWIC procured and provided launch, satellite, financing, and insurance services as a one-stop shop to countries by working through the appropriate SOEs.[10]

However, by the early 2010s, provincial and local governments acknowledged the financial difficulties associated with a state-driven growth model, and they turned to market forces and commercial investments to continue pursuing their interests. From this shift came the 2014 State Council’s Guiding Opinions on Innovating Investment and Financing Mechanisms in Key Areas (Document 60), is widely credited with kicking off the commercial space industry in China. In the document, the government recognizes the new role government spending will play in “guiding and driving” commercial investment in socially important areas.[11]

| While it became clear that China was pursuing a market-forward approach to space development, it is also important to define what the implementation of market forces looks like within the Chinese system. |

Document 60 also joined a flurry of guidelines and laws in 2014 that aimed to promote public-private partnerships, demonstrating that the Chinese were beginning to experiment with their potential to bring market forces to bear through pilot programs and establishing a “leading group” of senior members of the CPC.[12] Only one paragraph of the document mentions the commercial space industry, highlighting remote sensing technologies and satellite navigation. Launch vehicles receive only a passing mention, with no mention of satellite communications. This document, along with the 12th five-year plan, would shape the implementation of market-enabling reforms in China’s space sector.

The 2015-2025 National Medium- to Long-Term Civilian Space Infrastructure Development Plan began to implement market reforms, as well as lay out a comprehensive plan for priorities, which would help anchor later commercial investments. The Plan identified three primary areas: satellite remote sensing, satellite communications and broadcasting, and satellite navigation and positioning.[13] It also outlined four principles of development, which include two specifically calling out the role private actors would play in achieving the goals of the plan:

1. Innovation-driven, autonomous development: The Plan calls for “independent innovation” as well as linking technical R&D to business applications, critical steps for enabling a commercial sector by allowing it to leverage existing R&D efforts while giving space for exploration of fields not currently considered by ministries.

2. Government guidance, open development: This section explicitly calls out the role of government in insisting on “top-level planning and overall coordinated management” while establishing mechanisms to promote sharing and industrialization of civil space infrastructure. In a strong message, the Plan “Give[s] free rein to the decisive role of the market in the allocation of resources” in support of a concerted push towards achieving an “open development plan” involving stakeholders across government, private, and social sectors.[14]

While it became clear that China was pursuing a market-forward approach to space development, it is also important to define what the implementation of market forces looks like within the Chinese system. In 2015, clear guidance on SOEs was issued, calling for their continued reform towards market-based systems, claiming that “The market entity status of some enterprises has not yet been truly established”.[15] The document continued on to segment SOEs based on the markets they participated in, ranging from established markets with clear market-driven competition where “State-owned capital can hold absolute control, relative control, or a minority stake,” to SOEs in industries “related to national security and the lifeline of the national economy,” which “should maintain the controlling position of state-owned capital and support non-state-owned capital participation.”[16] This represents a clear direction towards the aerospace SOEs, which have continued to position themselves as critical partners to the Chinese government’s space ambitions and smaller commercial firms.

China’s government’s latest 2021 white paper on space activities expressly calls out the need for SOEs to engage in “the transfer and transformation of space technologies” to commercial actors, as well as an ecosystem where “large, small, and medium-sized enterprises advance in an integrated way.” This concept pairs with SOE reforms to establish a framework for the commercialization of China’s space sector. China will likely maintain SOEs like CASC and CASIC as providers of infrastructure and space technologies critical to national goals, while simultaneously encouraging them to selectively apply market-based principles when beneficial. Simultaneously, large SOEs and state enterprises will play a key role in anchoring and supporting the commercial space industry, which will be allowed to commercialize technologies and products for societal development.

While these commercial firms may compete with SOEs in certain sectors, it is clear that the Chinese government wishes to retain SOE control over critical services and space technologies. A key example of this is the “commercial” procurement of China’s next-generation cargo spacecraft. The two winners, Innovation Academy for Microsatellites of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (IAMCAS) and the Chengdu Aircraft Design and Research Institute under the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), are government-run and SOE-run, respectively.[17] This makes it clear that China’s commercial sector will remain largely quasi-governmental; however, attempts at venture-backed innovation have been explicitly encouraged.

Premier Li Qiang specifically called out the promise of commercial aerospace efforts in the 2025 work report, as well as the importance of supporting “unicorn enterprises and gazelle enterprises.”[18] Unicorn companies are private entities with valuations over $1 billion, while gazelles are startups with rapidly growing revenues and valuations at $100 million,[19] highlighting the importance of these companies demonstrates an awareness that much of China’s innovation across sectors depends on stimulating a diverse base of commercial innovation. The following section will identify the role SOEs play in building and supporting that commercial ecosystem.

Provincial and local policy efforts to stimulate a commercial space industry

Chinese innovation policy is uniquely decentralized, with national policy guiding provincial actions while most funding is disbursed by provincial and local governments. This has led to a proliferation of commercial space “action plans” by provinces across China. These plans set detailed goals for the development of local industries, universities, and investment funds. This decentralized approach has led many commercial space enterprises to decentralize operations, to capture as much government support as possible, giving rise to the national landscape seen today.[20]

SOEs as anchors for commercial hubs

Several scholars point to several hubs in China’s commercial space ecosystem as a key facet of its space landscape. Most notably, Beijing has attracted more than 200 commercial space ventures through a combination of factors. Both CASC and CASIC are headquartered in the region, providing a large talent base for commercial firms to engage.[21] Chinese firms and provinces both specifically pursue a strategy of “agglomeration,” which seeks to maximize knowledge spillovers, access to talent, infrastructure, government support, and suppliers. These hubs are “anchored” by SOEs, which build infrastructure and talent bases that attract commercial firms.[22] In many cases, CASC and CASIC are directly enlisted by local provinces to establish hubs, with Xi’an’s National Civil Aerospace Industrial Base a direct cooperation between local governments and CASC.[23] Wuhan has engaged with CASIC to construct the Wuhan Aerospace Base, and SAST has partnered with Ningbo to develop a commercial spaceport and industrial base in the region.[24]

| Without strong intellectual property protection laws and governmental R&D freely available to the commercial industry, brain-drain from leading SOEs enables commercial firms to innovate without massive investments in human capital and R&D. |

Beyond infrastructure, a key factor in the success of commercial firms is their access to talent. A prominent case study of commercial firms benefiting from SOE-developed talent is Zhang Xiaoping’s 2018 departure from the Xi’an Aerospace Propulsion Institute, a CASC subsidiary, to DeepBlue Aerospace. After his departure, the SOE claimed that he was “poached” and that his absence would severely impact lunar lander development efforts.[25] This brought wider attention to the issue of commercial firms poaching talent from SOEs, with an official claiming that several commercial space startups have set up headquarters nearby, explicitly aiming to poach talent from his company, offering wages three to five times higher.[26] Additionally, almost all employees at key Chinese startups like iSpace come from SOEs like CASC and CASIC.[27]

Without strong intellectual property protection laws and governmental R&D freely available to the commercial industry (ex. NASA), brain-drain from leading SOEs enables commercial firms to innovate without massive investments in human capital and R&D. CASC responded to the incident by stating it aims to “build a commercial aerospace community.”[28] In 2019, CASC delivered a keynote at the Commercial Aerospace Summit Forum titled: “Model Innovation, Openness, Win-Win Cooperation, and Joint Development of Commercial Aerospace.”[29] The keynote showed CASC was implementing rocket designs specifically for small satellites, constellations, and tailored inclinations, all desired by commercial industry. In addition, CASC committed to continued exploration of “new models of commercial aerospace,” as well as “establish a commercial aerospace industry chain,” showing that it sought to build commercial capabilities in partnership with a broader ecosystem, embracing the role of SOEs as anchors for commercial space hubs.

SOEs as R&D engines for innovation

As alluded to previously, SOEs play a critical role in China’s innovation ecosystem, linking universities, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and commercial firms. CASC and its subsidiaries have inked several deals with universities and the Chinese Academy of Sciences to develop R&D capacity in service of innovation.

A 2012 CASC agreement with the CAS highlighted a history of collaboration ranging from DongFangHong-1, China’s first satellite, to “manned spaceflight and lunar exploration.” The agreement aims to deepen collaboration on basic research, talent maturation, and specific areas including electronics, ground stations, and materials.[30] A 2016 agreement between Tsinghua University and CASC highlighted the need for resource sharing, technology transfer mechanisms, and talent training programs, as well as collaborative research across a broad range of aerospace technologies.[31] Most notably, in 2010, CASC spent 500 million yuan (about $70 million) to create the Harbin Institute of Technology Aerospace Science and Technology Innovation Research Institute, China’s largest aerospace research institute at the time.[32] Harbin Institute of Technology is one of the “Seven Sons of National Defense” run directly by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, spends almost 2 billion yuan (about $300 million) on defense R&D, and sends over 20% of its graduates to CASC, CASIC, and AVIC.[33] CASC has more than 20 agreements with universities across the nation.[34]

SOEs also operate independent research laboratories, integrated within China’s broader laboratory system. Two main categories exist: State Key Laboratories (SKLs) and Defense S&T State Key Laboratories (DSTKLs). While the vast majority are overseen by the Ministry of Education, the Chinese Academy of Science, and various other government ministries, a few are overseen by CASC and other large SOEs. CASC supervises 15 SKLs, as well as 16 national engineering research centers, which help apply the basic research developed at SKLs to physical systems, acting as the backbone of the nation’s innovation system.

Looking to encourage a broader innovation ecosystem, MIIT, CASC, and CASIC have partnered to host China Aerospace Innovation & Entrepreneurship Competitions across the country aimed at improving the commercialization of innovative research and products from smaller firms and universities in service of the “space dream” outlined by Xi Jinping.[35] Winning teams are rewarded with prizes, as well as attention from SOEs, investors, and the government.

This innovation is diffused through various mechanism, including the talent rotation mentioned earlier, as well as formal mechanisms such as a “matchmaking” conference hosted by the Cangzhou local government, which invited CASC, CASIC, local universities, and more than 200 enterprises from the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region to discuss potential cooperation between the large SOEs and private firms to build a “new model of integrated development of aerospace technology” in the region.[36] CASC’s “Technology Transfer Base” in Cangzhou seeks to build upon these efforts by converting the “advanced technologies” developed by “Manned spaceflight, lunar exploration, the launch of the Gaofen series of satellites” into “‘new engines’ for the high-quality development of local economies.”[37] Additionally, the local Aerospace Industrial Park hosts consultants from SOEs to aid in project management and investment evaluation.[38]

SOEs as backers for commercial space ventures

SOEs support commercial enterprises in two ways: either by creating commercial subsidiaries aimed at commercial operations subject to market forces or by backing existing commercial enterprises through capital investments.

CASIC’s Wuhan-based ExPace subsidiary is one of the first quasi-commercial entities in China’s commercial space landscape. Founded in 2016 to market the Kuaizhou series of launch vehicles, directly based on the DF-21 missile,[39] it represented a classic attempt by SOEs to commercialize operations through passing on operations to a commercial entity. The first launch of the KZ-1A rocket would be a satellite developed by CASIC itself.[40] Alongside mention of ExPace, CASIC’s Chairman, Gao Hongwei, emphasized CASIC's role in “vigorously promoting the development of the commercial aerospace industry.” [41]

| An unwillingness to allow commercial enterprises to take on critical facets of the civil and military programs will prevent commercial firms from ever reaching the scale necessary to conduct significant levels of R&D, as well as to benefit from economies of scale. |

China Rocket represents CASC’s attempt at commercialization by allowing commercial procurement of the Long March series of rockets developed by CALT. In addition to being a simple operator and vendor, mirroring CGWIC’s business in the 1980s and 1990s, China Rocket has also developed the Jielong series of rockets, funded purely through “social capital” to serve commercial small satellite constellation needs.[42] In addition, vendors were selected on the basis of cost competition, allowing a much cheaper development process. While ExPace seeks to market a civilian conversion of existing military hardware, China Rocket’s internal development of the Jielong rocket represents a much more fulsome attempt to adapt to market demands, although it aims to complement the existing Long March series rather than offer a commercial alternative.

CASC’s investment arm, China Aerospace Investment Holdings (CAIH), has described industrial investment as critical to stimulating a commercial spaceflight industry.[43] It directly calls out the importance of fundraising to SpaceX’s success, which at the time had undergone 46 rounds of financing at a valuation of $130 billion. CAIH has supported CASC’s commercial subsidiaries, including China Rocket and Liquid Rocket Engine. It also seeks to invest in small and medium enterprises under the mantra, “Invest early, invest in small businesses, invest in technology.”[44] Through its support, CAIH seeks to build a diverse and robust supply chain, benefitting CASC, as well as commercial space enterprises across the nation.

Importantly, CAIH recognizes the challenges in funding ambitious technical projects, which it describes as needing financial support that understands their “long cycle and high risk” nature. CAIH also identifies the well-known valley of death, from patent to commercial product, and aims to support promising startups through this “perilous leap.”[45] CAIH participates as a Limited Partner (LP) in various venture capital funds aimed at supporting commercial enterprises in: aerospace information technology,[46] military aerospace technology,[47] and satellite technology applications.[48] This integration of venture capital and industrial capacity creates a powerful alignment of incentives for broader supply chain support, with benefits to commercial spaceflight enterprises, yet it remains to be seen if CAIH will continue to support CASC commercial subsidiaries at the expense of a truly competitive market. Despite this, China Rocket and Liquid Rocket Engine do provide key enabling technologies to China’s commercial sector, helping companies avoid R&D costs by providing launch and propulsion technology at market-competitive prices.

Conclusion

SOEs play a massive, and understudied, role in shaping China’s commercial ecosystem. Through deep partnerships with local governments and universities, they form the backbone of China’s commercial space clusters. SOEs are also critical links in the “triple-helix” innovation system among industry, academia, and government, and their well-trained personnel bring critical know-how to commercial enterprises. Finally, they provide key financing to commercial subsidiaries, which develop products and services that help enable industry-wide innovation, while simultaneously investing in commercial space enterprises and ensuring robust supply chains, which benefits all participants. Existing literature also demonstrates the potential for SOEs to act as effective complements to private enterprises in R&D heavy industries, although this requires careful policy oversight and autonomy to be effective.[49]

However, SOEs have been subject to numerous reforms and directives, out of a recognition that they have failed to evolve into agile, market-oriented organizations. An unwillingness to allow commercial enterprises to take on critical facets of the civil and military programs will prevent commercial firms from ever reaching the scale necessary to conduct significant levels of R&D, as well as to benefit from economies of scale. China’s megaconstellation landscape is dominated by two companies, China SatNet and Shanghai SpaceCom (SSST). Both have about 100 satellites on orbit, far behind western companies: SpaceX’s Starlink has more than 9,000; OneWeb has about 650, and Amazon Leo has 180. Their deployment has been hamstrung by technical issues and launcher shortages,[50,51] demonstrating the challenges China’s space ecosystem is facing in scaling to match western capabilities. Additionally, China SatNet is an SOE, while SSST is a private enterprise, but effectively backed by the Shanghai government and Chinese Academy of Science.[52]

This structural exclusion of Chinese commercial firms from high-value, high-scale activities has led to much smaller headcounts compared to similar American firms. Figure 2 demonstrates this imbalance.

Figure 2: Headcounts of Chinese Firms and American Counterparts

| Chinese Firms | American Firms |

|---|---|

| GalaxySpace(700) [53] | SpaceX (13,000) [54] |

| Orienspace (70) [55] | Blue Origin (10,000) [56] |

| ChangGuang Satellite (587) [57] | Rocket Lab (2,100) [58] |

| Deep Blue Aerospace (200) [59] | Relativity Space (2,000) [60] |

| iSpace (200) [61] | Planet (970) [62] |

These smaller firms represent a minuscule fraction of the Chinese aerospace workforce, making large-scale R&D and innovation difficult. More than 3,500 employees are working on SpaceX’s Starship program in South Texas alone, and this is before the program has reached operational levels.[63] It remains to be seen if Chinese firms can effectively match the innovations in launch and satellite technology that have revolutionized the space industry in the United States, yet it is becoming increasingly clear that SOEs will play a critical role in Chinese efforts to build a globally competitive commercial space industry.

References- https://eastasiaforum.org/2021/05/05/can-chinas-commercial-space-sector-achieve-lift-off/

- https://www.state.gov/report/custom/bf839f4338

- https://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/world/china/casic.htm

- https://spacenews.com/china-outlines-intense-period-for-human-spaceflight-robotic-exploration-and-satellite-constellations/

- https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-05/China_Space_and_Counterspace_Activities.pdf

- https://www.state.gov/report/custom/bf839f4338

- https://www.upi.com/Archives/1986/05/19/China-offering-commercial-satellite-launch-services/2742516859200/

- Pg 5-6, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep13661?seq=11

- https://www.reuters.com/article/business/media-telecom/special-report-in-satellite-tech-race-china-hitched-a-ride-from-europe-idUSL4N0JJ0J3/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0265964623000413

- https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-11/26/content_9260.htm

- https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/public-private-partnerships-china.pdf

- Pg 5, CSET, National Medium- to Long-Term Civilian Space Infrastructure Development Plan (2015-2025)

- Pg 4-5, CSET, National Medium- to Long-Term Civilian Space Infrastructure Development Plan (2015-2025)

- https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-09/13/content_2930440.htm

- https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-09/13/content_2930440.htm

- https://english.news.cn/20241107/0b40225340884ea996fb65ad0df1fa04/c.html

- https://www.chinaiplawupdate.com/2025/03/premier-li-qiang-delivers-chinas-2025-work-report-strengthen-the-protection-of-intellectual-property/

- https://www.scmp.com/economy/economic-indicators/article/3272676/what-are-chinas-gazelle-enterprises-and-how-do-they-differ-unicorns?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14777622.2025.2569311

- Pg 37, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/Conference-2020/CASI%20Conference%20China%20Space%20Narrative.pdf

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14777622.2025.2569311#abstract

- https://en.shaanxi.gov.cn/business/dz/ndz/201708/t20170820_1594620.html

- https://spacenews.com/ningbo-wenchang-to-construct-chinese-commercial-spaceports/

- https://gs.ifeng.com/a/20180928/6915655_0.shtml

- https://news.jstv.com/a/20180927/1538042436197.shtml

- https://gs.ifeng.com/a/20180928/6915655_0.shtml

- https://gs.ifeng.com/a/20180928/6915655_0.shtml

- https://www.spacechina.com/n25/n2018089/n2018151/c2792961/content.html

- https://www.cas.cn/xw/zyxw/yw/201207/t20120703_3608589.shtml

- https://www.cast.cn/3g/news/4210

- https://chicago.china-consulate.gov.cn/chn/ywsz/kj/202508/t20250807_11684245.htm

- https://unitracker.aspi.org.au/universities/harbin-institute-of-technology

- https://www.spacechina.com/n25/n1991299/n1991343/index.html

- https://tech.sina.cn/d/tk/2019-04-24/detail-ihvhiewr7930844.d.html

- https://www.cangzhou.gov.cn/cangzhou/c100079/202009/6db883060ee2472daecf60aa5fff62a5.shtml

- https://www.imsilkroad.com/news/p/387180.html

- https://www.imsilkroad.com/news/p/387180.html

- Pg. 38, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/Conference-2020/CASI%20Conference%20China%20Space%20Narrative.pdf

- https://web.archive.org/web/20201204225826/http://www.parabolicarc.com/2017/12/20/expace-raises-182-million-small-satellite-launchers/

- https://www.cnsa.gov.cn/n6758823/n6758838/c6808256/content.html

- https://www.globalsecurity.org/space/world/china/jielong-1.htm

- https://www.spacechina.com/n25/n2018089/n2018151/c4085673/content.html

- https://www.spacechina.com/n25/n2018089/n2018151/c4085673/content.html

- https://www.spacechina.com/n25/n2018089/n2018151/c4085673/content.html

- https://investincq.com//index.php?c=content&a=show&id=478market-competitive1

- https://www.sastind.gov.cn/n10086200/n10086344/c10202775/content.html

- https://www.jiemian.com/article/2095095.html

- Link to source</li>

- https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3319163/has-qianfan-satellite-network-chinas-starlink-rival-run-trouble

- https://www.china-in-space.com/p/shanghai-backed-qianfan-constellation

- https://spacenews.com/shanghai-firm-behind-g60-megaconstellation-raises-943-million/

- https://paper.people.com.cn/rmrbhwb/pc/content/202504/08/content_30066419.html

- https://www.forbes.com/companies/spacex/

- https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/467659-63?utm_source=chatgpt.com#overview

- https://www.space.com/space-exploration/private-spaceflight/jeff-bezos-blue-origin-laying-off-1-000-employees-reports

- https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/340754-86

- https://stockanalysis.com/stocks/rklb/employees/

- https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/266267-08

- https://www.relativityspace.com/about

- https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/230465-17

- https://stockanalysis.com/stocks/rklb/employees/

- https://builtin.com/articles/starbase-spacex-elon-musk#:~:text=Summary:,site%20for%20its%20Starship%20program.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.