The Artemis Accords at fiveby Jeff Foust

|

| “This is now an environment that has to have norms and standards and rules, and that’s what we’ve done,” said Kshatriya. “It’s a bulwark against chaos.” |

However, Latvia hasn’t yet actually signed the Accords, and thus in the eyes of NASA and the State Department, which jointly oversee the document outlining best practices for sustainable space exploration, isn’t yet part of the Artemis Accords family. “We’re now up to 59 countries,” said Valda Vikmanis, director of the Office of Outer Space Affairs at the State Department, during one panel at the event at the Meridian International Center. (A signing ceremony is planned for early next year.)

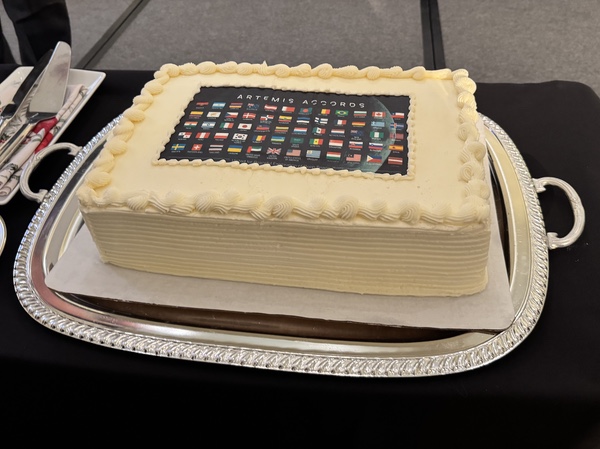

On the side that the Accords has 60 members? Captain Pike and a cake.

“When we started our journey on this show, there were only nine signatories, and now there are 60, which is just amazing,” said Anson Mount, the actor who plays Christopher Pike on “Star Trek: Strange New Works,” singing the praises of the Accords in a video shown at the event that had been recorded on the set of the Enterprise bridge. (The name “Artemis Accords” was inspired from Star Trek’s Khitomer Accords, the peace treaty between the Federation and the Klingon Empire.)

The cake, meanwhile, was decorated with the flags of the countries that have joined the Accords: 60 of them, as it turned out. “It’s a legally binding cake,” quipped Mike Gold, president of civil and international space at Redwire who helped lead the development of the Accords when he was at NASA.

Whether the Accords has 59 or 60 countries as members for now, those at the event did agree that the Accords has been a success in lining up support for rules and norms of behavior building upon the Outer Space Treaty and other international agreements, but not articulated in detail before.

“This is now an environment that has to have norms and standards and rules, and that’s what we’ve done,” said NASA associate administrator Amit Kshatriya in a keynote at the event, discussing the rapidly increasing number of launches and satellites in orbit over the last several years. “It’s a bulwark against chaos.”

The Artemis Accords came out of the broader Artemis lunar exploration effort started in the first Trump administration. “You can’t get the Artemis Accords without Artemis, and really that began by saying that America will return to the Moon,” said Gold.

Gabriel Swiney, a space lawyer at the State Department at the time, recalled negotiating an agreement with Japan for contributions to the Gateway. The Japanese noted that agreement didn’t extend to broader issues of going to the Moon together.

“We do need to bring our values your values and norms of behavior with you, but we hadn’t actually figured out what that means,” he said, noting the lack of details in the Outer Space Treaty. “We needed something to bridge that gap between the treaty and mission planning. So that is what drove the Accords and the content of the Accords.”

| “The Artemis Accords is a set of principles and not just a written document. I think we should execute,” Kaneko said. |

That idea gained support at NASA, including from the agency’s administrator at the time, Jim Bridenstine, as well as the White House. “I don’t believe it's just our astronauts that we send into space. I don’t believe it is just our robots that we send into space. It’s our values that we send into space,” said Scott Pace, who was executive secretary of the National Space Council in the first Trump administration. The Accords, he said, became the “obvious complement” to the Artemis exploration strategy that would bring in international and commercial partners.

Despite that support, there were a lot of people within the US government skeptical the Artemis Accords could be feasible, Swiney said. “We had some hard conversations with people saying, ‘You’re going to cause negative reaction, you’re going to cause blowback,’” he recalled.

By contrast, he said there was an “incredible appetite” among potential signatories for something like the Artemis Accords. “Don’t you want to be part of shaping the future of humanity going to Moon?”

Some countries, like Japan, got on board quickly. Yosuke Kaneko of Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said his government first heard about planning for the Accords in 2019, and became one of the first eight countries announced as signatories in October 2020. “Anyone who is familiar with government processes know that’s a laser-fast timeline,” he said.

The Accords today

That initial group of eight has now grown to 59 (or 60). From an outsider’s perspective, many of the announcements about the Accords focus on which countries have signed on, giving it something of a stamp-collecting vibe: who has signed, but not what they’re doing.

“The Artemis Accords is a set of principles and not just a written document. I think we should execute,” Kaneko said. “Japan and all of the other countries are responsible to execute what was written in the Artemis Accords and accumulate the good practices because, in the end, these will become the normal behaviors on the lunar surface.”

Part of that includes fleshing out some of the principles in the Accords. At the International Astronautical Congress in Sydney, Australia, in September, representatives of 39 of the then-56 signatories met to discuss progress on implementing aspects of the Accords.

One topic was the article about deconfliction of space activities, including setting up “safety zones” around such activities as a means of avoiding harmful interference.

“A safety zone is not well defined,” said Ahmad Belhoul Al Falasi, a UAE government minister who chairs the board of the UAE Space Agency, at a press conference following the meeting. The UAE was one of the co-chairs of the meeting alongside Australia and the United States.

One issue, he said, is how large should a safety zone be. “A second point is, what is considered harmful interference?”

Other topics at that meeting included open sharing of scientific data, another Accords provision, as well as mitigating orbital debris, a particular concern around the Moon where there are fewer stable orbits and no atmosphere to help deorbit debris. “Preserving lunar orbits and keeping them sustainable for exploration for all countries was an ongoing focus,” said Enrico Palermo, head of the Australian Space Agency, at the press conference.

The current signatories also discussed how to bring in more countries to the Accords. One issue, they said, is explaining the relevance of the Accords to countries with limited space activities, including some who have already signed.

“Some members are trying to find their value add for the Accords,” Al Falasi said. An upcoming workshop in Peru, he added, will explore how to ensure all signatories can actively participate in discussions. “We want to have a very well-defined way that enables these countries to contribute.”

At the Meridian event, Vikmanis said the Accords has been useful in discussions about the use of space resources. One of the provisions of the Accords endorses the utilization of space resources and does not consider it national appropriation, which is forbidden in the Outer Space Treaty.

| The Accords, said Vikmanis, “has really illustrated, to many people, the power of US space diplomacy but also, equally, the power of space diplomacy in general.” |

“There’s no question that we need to be able to extract lunar resources to sustain a human presence on the lunar surface and to go on to Mars. That’s not under debate. The question is, how do we do that responsibly?” she said. “The Accords has provided us with a very good forum in which to have this discussion.” That includes advancing those discussions elsewhere, such as the UN’s Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

“One of the things about the Accords,” she added, “is that it has really illustrated, to many people, the power of US space diplomacy but also, equally, the power of space diplomacy in general for advancing these discussions.”

A cake at a Meridian International Center event in December marking the fifth anniversary of the Artemis Accords, with 60 countries displayed. (credit: J. Foust) |

Looking ahead

The Accords, like the rest of the Artemis effort, survived the transition from the first Trump administration to the Biden administration. The Accords arguably thrived during that time, going from nine to more than 50 signatories during that time.

“I saw what doors it opened for NASA and the US across the world,” said Alicia Brown, executive director of the Commercial Space Federation and head of legislative affairs for NASA when Bill Nelson was administrator. “Sen. Nelson would talk about going across the world and he would get meetings that others in the US government weren’t able to get, because of the NASA meatball and because he had something to offer them that was easy for them to sign up and increase our partnership.”

The Accords appear to have also survived the shift to the second Trump administration. While the pace of new signatories slowed for much of the year, three countries—Hungary, Malaysia, and the Philippines—all signed the Accords in October, along with Latvia’s announcement of its intent to sign.

“When I took this job, I had a number of people say, ‘I wonder how the administration is going to support the Artemis Accords,’” said Kathleen Karika, a senior advisor at NASA who joined the agency earlier this year. She said the administration is supporting the Accords and looking to making them more substantial.

“The Accords are just a great tool across the board,” she said. “The Accords are about having countries that are like-minded joining us.”

| “We had hoped, in our wildest dreams, that this would take off and become more of a global thing,” Swiney said of the Accords, “but that was a really big reach goal.” |

“By expanding and implementing the Accords, the United States and our fellow signatories are pushing back against the aggressive use of outer space and are working together to shape space activities in a way that benefits all,” said John Thompson, senior bureau official at the State Department’s Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, in a closing keynote.

“The principles of the Accords matter more than ever,” he added. “We must not only continue to expand the Accords by securing new signatories, we must also actively use this community to keep space safe and open.”

“The lesson I’ve learned is that you can be really ambitious,” said Swiney, now at the Office of Space Commerce. When drafting the Accords, he said he was prepared to be satisfied with just that initial group of eight countries.

“We had hoped, in our wildest dreams, that this would take off and become more of a global thing,” he said, “but that was a really big reach goal.”

At the end of the two-hour event, the promised “legally binding” cake was rolled out. Sure enough, there were 60 flags on it, neatly arrayed in five rows of 12 flags each. Latvia was included in the lower right corner, late additions alongside Hungary, Malaysia and the Philippines.

The panelists then posed for pictures with the cake and ceremoniously cut into it. Someone then said, “Cut Latvia first.”

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.