The Backfire bomber controversyby Dwayne A. Day

|

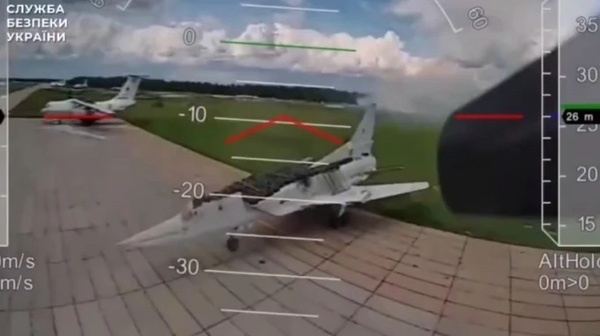

A Backfire bomber in Russia about to be struck by a Ukrainian drone in June 2025. At least four Backfires were destroyed during the attack, and two others damaged. (credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

Satellite images from Maxar and Planet showing destroyed Backfire bombers. The exact number of Backfires remaining in the Russian air force is not publicly known, but is only a few dozen, probably less than 60. Approximately ten have been destroyed in the war against Ukraine. (credit: Maxar and Planet) |

The Backfire has been in service for many years, and more than 50 years ago, satellite photos of the bombers helped kick off a dispute within the US intelligence community. The controversy raged for years and had international implications, one of many times that CIA and military intelligence analysts clashed over the interpretation of intelligence data. The dispute was how much fuel the bomber could carry, which determined how far it could fly, and therefore whether it was a tactical or strategic bomber and subject to an international arms limitation treaty. American satellites played a major role in gathering data on the Backfire throughout the 1970s as this controversy raged. Like the earlier bomber and missile gaps of the late 1950s, as well as the 1960s disputes over the Soviet SA-5 surface-to-air missile, CIA analysts argued one set of data, whereas military officials took a far more alarmist position.

The Tu-22M Backfire was a medium-range bomber first flown in the late 1960s and entered production in the 1970s. The CIA and USAF argued over the range of the bomber. It is still in service today, although the last one was built over 30 years ago. (credit: Alexander Beltyukov Wikimedia Commons) |

KAZAN-A

Although not as famous in the West as the MiG-21, MiG-25 Foxbat, or MiG-29, the Backfire is one of the better known Soviet bombers, primarily due to the late Tom Clancy. Clancy’s novel Red Storm Rising, about a theoretical World War III, featured a notorious chapter, “The Dance of the Vampires,” where the Soviet air force undertook a clever raid on the US Navy involving Backfires, among other planes, and inflicted significant damage. In the 2002 movie The Sum of All Fears, based on a Clancy novel, a flight of Backfires causes major damage to the aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis, although Clancy said that the Navy only agreed to allow the ship to be filmed if the Backfires didn’t sink it in the movie.

Backfire bombers preparing for takeoff. The Soviet Union built almost 500 Backfire bombers. They were split between medium-range bombing and naval strike roles. (credit: Alexander Beltyukov Wikimedia Commons) |

Unlike its larger and older brother, the Tu-95 Bear strategic bomber, which is ungainly and has propellers, the Backfire is sleek and dart-like, with swing-wings and engines that burn purple-blue flames—sometimes with a yellow plume from high-sulfur fuel—as it climbs from the runway at full power. The Backfire looks like a badass killer.

The Backfire is impressive from almost any angle. Its two engines operating in afterburner are dramatic. (credit: Andrej Shmatko Wikimedia Commons) |

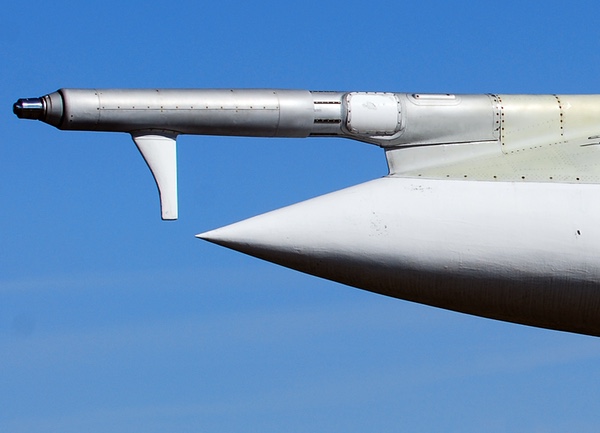

The Backfire is equipped with a tailgun for any adversary dumb enough to get behind the aircraft. (credit: Clemens Vasters Wikimedia Commons) |

The Tu-22M was developed by the Tupolev Design Bureau starting in the mid-1960s. Although it had the same initial designation as the Tu-22 Blinder medium-range bomber, this was a political ruse. Just as the American military has sometimes built almost entirely new aircraft with only a minor designation change over their predecessor to secure political approval and funding (see, for instance, the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet), the Soviet military occasionally did the same. Although it also had swing wings, the Tu-22M was an entirely new aircraft compared to the Blinder. It was designed for two missions: medium-range bombing, and attacking American aircraft carriers.

The Kazan aircraft production facility, seen in this 1972 US reconnaissance satellite photo, was responsible for many Cold War era bombers. Although it is still active today, its production rate is incredibly low. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

In August 1969, an American reconnaissance satellite spotted a new swing-wing bomber at Kazan Airframe Plant Gorbunov 22. The National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) designated this bomber as KAZAN-A, and it retained this designation for a couple of years until it gained the NATO designation Backfire. (For clarity, Backfire will be used hereafter.)

The Kazan aircraft production facility where the first Backfire bomber was photographed by an American reconnaissance satellite in the late 1960s. In this 1973 satellite photo, at least one Backfire bomber is visible. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

In March 1970, a KH-4B CORONA satellite, mission 1109-1, again photographed the Kazan Airframe plant. A mission report indicated that the satellite photos did not reveal any of the bombers at that location or at the Ramenskoye flight test center near Moscow.[1] In June 1970, KH-4B CORONA mission 1111 was more successful: photography from the mission identified the probable third prototype Backfire, at the Kazan Airframe Plant. The other two Backfires were seen at Ramenskoye.

Ramenskoye, known to the Russians as Zhukovsky, was the Soviet equivalent to Edwards Air Force Base, the location of flight tests of new military aircraft. Another aircraft was observed at Akhtubinsk flight test center in April 1971. These were all Backfire A models, although intelligence analysts did not know that they would soon see a new model that would result in A and B designations. In satellite photos that followed, the A models were only observed at training airfields, and none were ever observed at operational bases. Only seven were produced, according to an NPIC assessment, and by 1983 all of them were no longer flying and were on static display.[2]

The Soviet Union's equivalent of Edwards Air Force base was Ramenskoye, outside Moscow. This is where much testing of the Backfire was conducted. In a 1980 U.S. reconnaissance satellite photo (top) several Backfires are visible. But fewer were at the facility in a 1982 satellite photo (bottom), probably because the aircraft was by then in full-scale production and fewer test flights were necessary. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

In November 1971, an American satellite photographed what was designated the Backfire B at Kazan. It had an increased wingspan and did not have enlarged pods like the Backfire A. These were originally thought to be landing gear pods, but were actually aerodynamic and were removed when it became clear they offered no benefits. In May 1972, a Backfire B was observed at Ramenskoye, and another at Akhtubinsk airfield in September 1972. It was not until April and May 1974 that the Backfire Bs were seen at the training bases of Ryazan/Dyagilevo Airfield and Nikolayev/Kulbakino Airfield[3]

Tu-22M Backfire bombers deployed to Nikolayev airbase in Ukraine in 1980. The deployment of the aircraft to the western USSR was an indication that they were intended for medium-range missions attacking Europe, not strategic missions attacking the United States. This airfield in Ukraine was destroyed by Russia in 2022. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

A third version, designated the Backfire C, was first identified at Ramenskoye in August 1977 and then spotted at Kazan in April 1978. It had a modified nose and air intakes. The prototype was destroyed by a fire at Ramenskoye. Initial deployment to the training base at Ryazam/Dyagilevo occurred in March 1981.[4]

Although the only released American satellite photos of Backfire bombers during this period come from CORONA and later HEXAGON reconnaissance satellites, the planes were almost certainly photographed by the much more powerful GAMBIT satellites. By the mid-1970s, GAMBIT images were providing resolution better than 30 centimeters on the ground, enabling photo-interpreters to make increasingly precise measurements of the objects they photographed such as the fuselage width of bombers. Planes like the Backfire could also be compared to other objects at the airfield, such as aircraft with precisely known dimensions, like the Tu-95 Bear. Based upon these images, and knowledge of aircraft engineering principles, it was possible to calculate how much internal volume of an aircraft would be available to hold fuel, generating an estimate for the maximum amount of fuel that could be carried. Based upon this estimate and assumptions about engine efficiency and flight profiles, it was possible to derive range estimates for the aircraft. But those calculations created controversy.

This 1984 satellite photo shows engine testing of four Backfire bombers, visible where the snow has been blown away. Peak annual production of the bombers was about 30 aircraft per year, and total production was just under 500 aircraft by the time it ceased in the early 1990s. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

Satellites provided two main types of information about the Backfire during the 1970s—initially providing technical information the plane, and later, indications of how it was being deployed, whether to strategic airfields or to the periphery of Europe.

Range estimates

Arguments over the range of the Backfire started in 1971 and continued over many years. The issue became more acute by 1973, when the bomber was due to be included in a high-level National Intelligence Estimate. Although there was a range of estimates for how far the Backfire could fly, if the plane was equipped for aerial refueling, it could certainly reach targets within the continental United States.[5] However, unlike the United States Air Force, the Soviet Union had a very limited refueling fleet—not many tankers capable of refueling strategic aircraft.

For the early 1970s, several US (and foreign) intelligence organizations generally agreed on the Backfire’s range. But by 1976 the issue had reached a boiling point within the US intelligence community. This was caused by a new, substantially lower, CIA estimate of the Backfire’s maximum range.

The key figure who pushed the military’s longer range estimate was Major General George Keegan, the Air Force’s Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence. Keegan was a hard-core Cold Warrior who, like the fictional General “Buck” Turgidson in Dr. Strangelove, was always smelling a big fat commie rat. As New York Times reporter William Burrows later wrote, “George Keegan worries about the Russians and deeply mistrusts them. But he despises the CIA.”[6] The CIA was about to enrage him.

Major General George Keegan was head of US Air Force Intelligence in the mid-1970s. He clashed with the CIA over many subjects, including the range of the Backfire bomber. He was wrong. (credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

By 1976, the CIA had engaged a still-classified organization to perform an estimate of the Backfire’s performance based upon the latest intelligence. The CIA had also hired aerospace contractor McDonnell Douglas to perform another analysis, although the contractor may have taken inputs developed by another office and did not generate their own. The CIA estimated that the bomber’s range was 2,222 kilometers (1,200 nautical miles), less than the previous estimate. The military, particularly the Air Force, objected to this conclusion. The CIA’s new range estimate was now substantially lower than previous estimates produced by North American Rockwell, General Dynamics, the Royal Air Force, and the Air Force’s Foreign Technology Division. This greatly annoyed Keegan, who wondered why all the other estimates were consistently higher, while the CIA’s was substantially lower. Keegan then wrote a letter to the CIA.[7]

The CIA office responsible for overseeing the new analysis wrote a detailed response to Keegan’s letter. It noted that the previous estimates had all been based upon the same set of assumptions: that most of the available volume was reserved for fuel, the thrust characteristics of the engines were those of an uprated SST engine, and optimum takeoff and cruise aerodynamics applied. Those assumptions were not validated. However, new intelligence information had become available that changed those assumptions. Exactly what that new information was is unclear from the declassified report. However, the security markings on the report indicate that it contained intelligence derived from satellite imagery, as well as communications intelligence. The report also referred to the design of the Backfire’s landing gear, and because the gear would not be visible to satellites, this implies that the CIA had other photos of the aircraft, probably while it was landing or taking off. According to one source, the CIA even had access to flight test telemetry from the Backfire. A recently declassified document indicates that the SAVANT II satellite was collecting aircraft telemetry in early 1971, although it is not clear what kind of aircraft telemetry.[8]

Two SAVANT series signals intelligence satellites were flown by the United States in the late 1970s. SAVANT II reportedly intercepted telemetry signals from Soviet aircraft tests, possibly including early Backfire flights. There is some indication that the US intelligence community had intercepted telemetry from Backfire test flights. (credit: NRO) |

At times, Keegan’s arguments (obviously developed by his staff) seemed rather esoteric, such as the angle of rotation of the aircraft lifting off the runway and whether it could benefit from ground effect during takeoff. The CIA analysts believed that these issues had little effect upon the plane’s maximum range. Keegan also seemed to be committing one of the cardinal sins of intelligence by conflating capability with intent. Some of his writings argued that because in some circumstances the Backfire could be used strategically, the Soviets would use it strategically, even though there was no evidence of them planning to do so (for instance, by building up their in-flight refueling fleet).

| An intelligence officer summarized the problem: “The evidence is inconclusive, the range of uncertainties is large, the analytical methodologies involved are exceedingly complex, and the answers one gets are determined to a large extent by the assumptions with which one starts.” |

Keegan also alleged that the newer Backfire B model had greater range due to its larger wing and elimination of the pods. But the CIA referenced an unpublished NASA study indicating that the larger wing had greater drag, which negated those benefits. He further claimed that an increase in the size of the production plant indicated an increase in Backfire production, but the CIA responded that 20% more floor space at the factory did not automatically mean more bombers—that space could instead be allocated to post-production maintenance of completed aircraft.

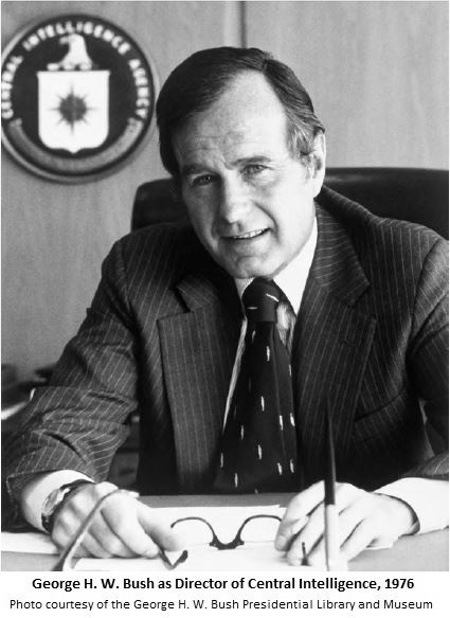

In August 1976, the Backfire controversy leaked to the press, generating unwanted attention for the CIA. Director of Central Intelligence George H.W. Bush wrote a letter to Brent Scowcroft, President Ford’s national security advisor, explaining the agency’s position and refuting General Keegan’s points.[9]

George Bush was head of the CIA in 1976 when the dispute over the Backfire’s range became public. He agreed to the Team B intelligence exercise, which undercut the CIA's analytical authority. (credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

By mid-August, Keegan again complained to the CIA about its analysis, and recommended two aerospace executives to participate in an independent assessment of the CIA’s analysis. The CIA accepted this recommendation, but there was clearly animosity between the agency and General Keegan.[10]

In response to Keegan’s latest complaint, an intelligence officer wrote an internal memo explaining the controversy. He noted that most of the intelligence community still believed that the Backfire was suited to a peripheral attack role, but that the Air Force was insisting that the Backfire was designed to perform a variety of missions, including intercontinental attack.[11]

The aircraft’s overall appearance seemed to indicate that it was designed to perform supersonic dash and low-altitude penetration of heavily-defended areas, hence its swing wings and pointy shape compared to earlier Soviet bombers. The Air Force’s position was in part based upon the assumption that, if the plane flew at subsonic speeds at high altitude, it would have longer range. Also, all Backfire bombers seen up to that point had in-flight refueling probes, supporting the Air Force argument that the plane was intended to fly long distances. If it was staged closer to the United States and flew one-way missions, it could of course travel even further to attack the United States.

Early Backfire bombers were equipped with refueling probes. This became a source of contention between the CIA and the US Air Force. If the plane was refueled, it could reach many targets in the United States. However, there was no indication that the Soviet Union was building up its meager fleet of refueling aircraft to support the Backfire. The Soviet Union, as part of a later arms control agreement, agreed to not equip the Backfire with refueling probes. (credit: Erik Gundersen Wikimedia Commons) |

It was still difficult to draw conclusions in part because the Backfire had only been in operational service since 1974, making it harder to determine Soviet intentions for the aircraft, although so far it had only been deployed for peripheral and naval strike roles. The intelligence officer, who worked for the US Navy, summarized the problem: “The evidence is inconclusive, the range of uncertainties is large, the analytical methodologies involved are exceedingly complex, and the answers one gets are determined to a large extent by the assumptions with which one starts.”[12]

By October 1976, the CIA produced an internal memo explaining the timeline of how it had come to new conclusions about the Backfire, noting that other members of the intelligence community were already aware of the new analysis a year and a half earlier, in April 1975. The Backfire dispute had become public in recent months. The CIA Director had testified in front of Congress about the aircraft’s range several times before the CIA had conducted its reanalysis, and more recently articles appeared in the press alleging that “the intelligence was slanted to support administration policy.” [13]

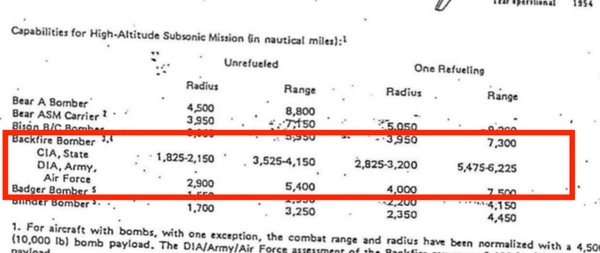

The range estimates produced by the CIA and other intelligence agencies in the late 1976 National Intelligence Estimate. The Backfire's actual range proved to be near the lower end of the CIA's estimate. (credit: CIA) |

National Intelligence Estimate NIE 11-3/8-76, produced in December 1976, included key judgments about current developments in Soviet programs. It stated that “Soviet intercontinental striking power would be increased if Backfire bombers were employed against the U.S. The Backfire is well suited to operations against land and sea targets on the Eurasian periphery using a variety of flight profiles, and it has some capability for operations against the U.S. on high-altitude subsonic profiles.”

It continued: “The Defense Intelligence Agency, the Assistant Chief of Staff, Intelligence, Department of the Air Force, estimate that the Backfire has significant capabilities for operations against the U.S. without air-to-air refueling. The Central Intelligence Agency and the Department of State estimate that it has marginal capabilities against the U.S. under the same conditions. With air-to-air refueling, the Backfire would have considerably increased capability for intercontinental operations, even in the case of the lowest performance estimate. In addition, the Backfire could be modified in various ways to improve its range.”[14]

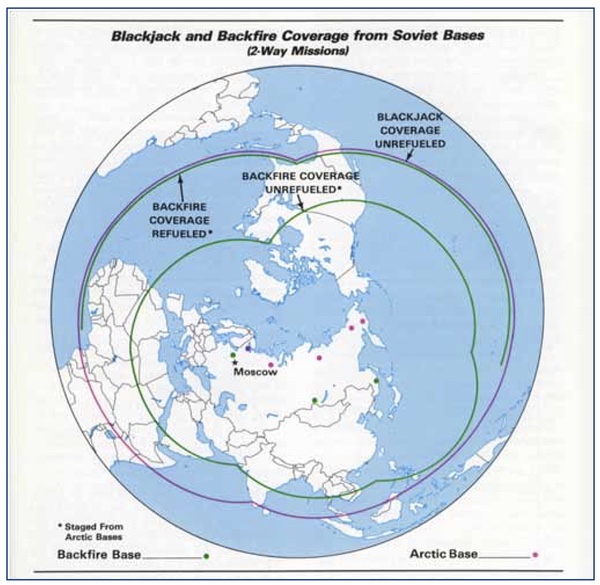

Range estimates for several Soviet bombers from the DoD publication Soviet Military Power. Without refueling, the Backfire could not reach much of the United States. The problem was that the Soviet Union did not have many tankers that could refuel a fleet of Backfires. (credit: Department of Defense) |

“We believe it is likely that Backfires will continue to be assigned to theater and naval missions and—with the exception of DIA, ERDA, Army, and Air Force—we believe it is correspondingly unlikely that they will be assigned to intercontinental missions. If the Soviets decided to assign any substantial number of Backfires to missions against the U.S., they almost certainly would upgrade the performance of the aircraft or deploy a force of compatible new tankers for their support. The Defense Intelligence Agency, the Energy Research and Development Administration, the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, Department of the Army, and the Assistant Chief of Staff, Intelligence, Department of the Air Force, believe the available evidence on Backfire employment indicates only that peripheral and naval attack are its current primary missions. Since the Soviets could use the Backfire’s intercontinental capabilities at their initiative, these agencies believe that the Backfire clearly poses a threat to the U.S., even without the deployment of a compatible tanker force or the upgrading of the aircraft’s performance. The Assistant Chief of Staff, Intelligence, Department of the Air Force, further believes that a portion of the Backfire force will have missions against the contiguous U.S.”[15]

The Central Intelligence Agency and State Department calculated the Backfire’s range as 3,525 to 4,150 nautical miles (6,528 to 7,686 kilometers) and therefore not a strategic weapon. The Air Force had determined its range at 5,400 nautical miles (10,001 kilometers), and therefore capable of reaching the continental United States. With refueling, the planes could fly significantly farther.

In March 1977, the Director of Central Intelligence was due to appear on the television program “Face the Nation,” and there was the possibility that he might be asked about the Backfire, considering a recent newspaper column in The Washington Star that had raised the issue. The director was advised that the official United States position at the SALT negotiations was that the Backfire was comparable to the Bison heavy bomber and should be counted as a heavy bomber, and the CIA’s position on the revised range estimate had not been made public.[16]

Counting bombers and Team B

Soviet bombers had been a source of contention in the US intelligence community before. In the mid-1950s a controversy had arisen about how many strategic bombers the Soviet Union had. It took several years, and overflights of Soviet airfields by U-2 reconnaissance planes, before the CIA was able to prove that the numbers had been over-estimated.[17]

| The Cold War Team B experiment was viewed with alarm by many people within the intelligence community because it established a precedent that if somebody did not like the conclusions that the intelligence analysts were providing, they could simply pick their own panel of experts. |

Even before the late 1976 National Intelligence Estimate, a larger dispute about Soviet weapons capabilities had started raging inside the intelligence community. In May 1976, President Gerald Ford created what was known as the “Team B” project to appoint a group of outside experts to look at the same data that the CIA was looking at and provide an alternative interpretation. This had resulted from charges that the CIA had consistently underestimated Soviet weapons production.

The Team B report was significantly more alarming than the CIA’s conclusions, estimating much greater Soviet weapons production and capabilities. Team B did not do its own estimates of the Backfire range. They simply compared the ranges produced by CIA and USAF.

The Team B report had been intended to only be an exercise, but the report was leaked soon after Jimmy Carter became president, and it was used by various people to argue that the Soviet Union was a bigger threat and growing faster than the CIA had been assessing. This was used to justify a bigger US defense buildup.

The Cold War Team B experiment was viewed with alarm by many people within the intelligence community because it established a precedent that if somebody did not like the conclusions that the intelligence analysts were providing, they could simply pick their own panel of experts and give them the same data to produce a result more to their liking. It undercut the CIA and made intelligence analysis more vulnerable to political manipulation.

In retrospect, Team B’s report was highly inaccurate and the CIA’s estimates proved to be much closer to the reality. For example, Team B predicted that the Soviets would have 500 Backfire bombers by 1984. By 1983, NPIC determined that the Soviets produced 30.5 aircraft per year from July 15, 1982 to July 15, 1983, a production rate that was not high enough to produce hundreds of bombers in a short time.[18] Whereas Team B had predicted 500 Backfires by 1984, the actual number was 235, and just under 500 when production finally ceased in 1993.

The numbers, and the range estimates, had increased importance because the United States and Soviet Union by the late 1970s were engaged in arms control limitation talks. If the Backfire was counted as an intercontinental bomber, then the Soviet Union had a much larger bomber force, especially if the United States also included the bombers that were clearly dedicated to naval attack. Ultimately, the two sides reached an agreement that the Backfire would not be counted as an intercontinental bomber as long as the Soviet Union agreed to not equip it for aerial refueling.

Deep Black

In his 1987 book Deep Black, about the development of American strategic reconnaissance, including then highly secret reconnaissance satellites, William Burrows wrote about the then-retired George Keegan. Keegan was, by his own admission, a hard-liner who had repeatedly warned about Soviet military capabilities and been largely ignored.[19]

Keegan had raised the alarm about numerous Soviet strategic developments. Deep Black recounted his concern about vast underground leadership bunkers to enable the Soviet Union to fight and survive a nuclear war. By the late 1970s he was warning about Soviet space-based laser systems. In 1978, after retiring from the Air Force, Keegan appeared on the BBC Panorama program “The Real War in Space” where he warned about Soviet space weapons, and in retired life he was a strident hawk who publicly spoke about Soviet weapons development based upon his five years as head of Air Force intelligence. Keegan’s previous access to top secret intelligence seemingly gave him credibility, but his public appearances unnerved many people in the intelligence community who had been trained to not even speak the word “satellite.”

Keegan believed that the military should have control of space reconnaissance assets and that military officers should be performing assessments of Soviet weapons capabilities. He did not believe that the CIA should be in control of the assets or making the assessments. Furthermore, Keegan believed that arms control agreements were having an insidious effect on the production of intelligence, by creating, in Burrows’ words “the misguided assumption that what must be seen will be seen.”

Keegan’s adversary during the early 1970s had been Director of Central Intelligence William E. Colby. Colby had become the CIA’s third-ranking officer in 1971 after serving in clandestine roles in Southeast Asia. Upon arriving at the CIA’s Langley headquarters, he had been exposed for the first time to the new array of high-tech intelligence collection systems. “I went on a tour of the aerospace technology factories on the West Coast and there had my eyes opened to the veritable science-fiction world of space systems, radar, electronic sensors, infrared photography, and the ubiquitous computer, all able to gather intelligence from high in the sky to deep in the ocean with astounding accuracy and precision,” Colby wrote in his memoir. Colby was later fired by President Gerald Ford in November 1975 after cooperating too closely with congressional investigations of CIA activities. He was replaced by George Bush, who later agreed to the creation of Team B, and became embroiled in the Backfire controversy.

William Colby was head of the CIA in the early 1970s and clashed with Major General Keegan over several intelligence issues. He was replaced by George Bush. (credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

Keegan’s belief that arms control negotiations skewed the intelligence collection was one that had been disputed within the strategic reconnaissance community since the late 1960s. The operators of American reconnaissance satellites believed that their primary mission was collecting intelligence on the Soviet strategic threat, and treaty monitoring was simply a subset of that activity, not a driver. In 1972, during discussions within the intelligence community about arms control and the need for new intelligence collection systems, an Air Force officer had pointed out that the intelligence collection itself was the most difficult challenge.[20] New intelligence requirements such as detecting Soviet Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicles, or mobile ICBMs were going to drive US intelligence collection whether or not they were banned by a treaty. The same would be true for other Soviet weapons developments.

Colby had argued that point himself: “Verification is nothing more than the continuation of our normal intelligence process. We’re going to cover Soviet weaponry whether there’s a treaty between us or not; we have to in order to protect our country against surprise.”[21]

The analysts

Decades after the dispute, historians and reporters were still trying to make sense of it. According to Robert M. Clark in Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach, both the CIA and Air Force Intelligence employed separate contracting teams at McDonnell Douglas to produce analysis of the Backfire.[22] The two teams arrived at different range estimates, and Clark wrote that “Each side accused the other of slanting the evidence.” However, although there is evidence indicating that CIA employed McDonnell Douglas to produce analysis of the Backfire, there is no evidence that the Air Force did as well.

Clark claimed that the Backfire analysis was an example of “premature closure” where previous predictions that the Soviet Union would develop a new intercontinental bomber led analysts to “cherry-pick” the evidence to support this view. “A serious consideration of Soviet systems designs and requirements, and of what the Soviets foresaw as threats at the time, would likely have led analysts to zero in more quickly on the Backfire’s mission of peripheral attack.”

Other factors may have led to the longer range estimate. Clark also wrote that the case illustrated a common analysis problem of presenting the worst-case estimate. “A U.S. bomber of Backfire’s size and configuration could easily have had intercontinental range,” Clark wrote, although Soviet bombers were less fuel efficient.

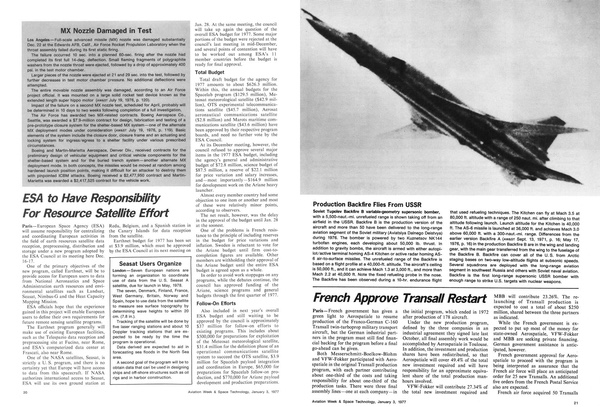

In 1977, Aviation Week and Space Technology published the first photo in the West of the Tu-22M bomber. This grainy photo and another one was used by aviation writer Bill Sweetman to produce a plan view of the aircraft and to estimate its fuel capacity and range. Sweetman’s estimate was within 8% of the actual fuel capacity of the aircraft. (credit: Aviation Week and Space Technology) |

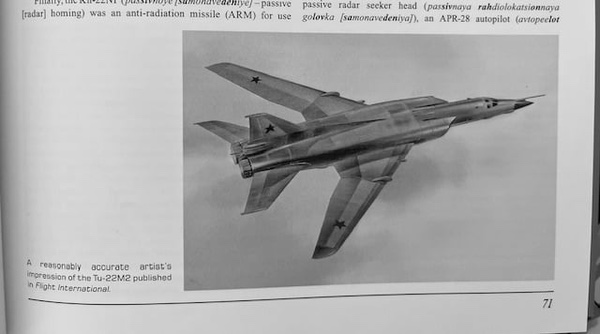

In contrast, aviation writer Bill Sweetman offered an alternative explanation. In 2015, Sweetman recounted how, in the late 1970s, he and fellow aviation writer Doug Richardson at the British magazine Flight International had conducted their own analysis of the Backfire’s range. In early 1977, their rival publication Aviation Week & Space Technology had published a grainy photo of a Backfire in flight.[23]

“The estimated basic dimensions had been published. So by enlarging and tracing the pic on the Flight artists’ Shufti Scope [a device that made it possible to draw 3D objects based upon a 2D image], and drawing a grid of lines parallel with the wingtip-to-wingtip line and the long axis, it was possible to construct a decent plan and side view. From there it was possible to estimate volume and fuel capacity,” Sweetman explained in a recent communication.[24]

This drawing of the Backfire was produced by an artist at Flight International, a competing magazine with Aviation Week. Bill Sweetman and a colleague produced it using a "Shufti Scope," a device for converting a photographed object into a drawing. (credit: Flight International via Bill Sweetman) |

“What we had independently concluded was that (1) the thin outer wings didn't hold much fuel and (2) you could not extend the fuel tanks forward to the aft cockpit bulkhead, because then almost all the fuel would be ahead of the center of gravity and the shift as fuel burned would be impossible, particularly with the short tail arm.”

They calculated that the Backfire carried 50 metric tons of fuel and therefore could not achieve the range claimed by the US Air Force. Sweetman also added: “When my colleague Charles Gilson (defence editor) was briefed by the UK Ministry of Defence and told that I was full of shit, he was shown a head-on pic that looked like a Backfire on approach. He was allowed to make a sketch that was quite helpful.” The article in Flight International also included new artwork of what the plane looked like from above.

“Not long after we published our numbers, I got a call from a puzzled engineer at McDonnell Douglas, who wondered how we had hit the same numbers his team had. I told him about my calculator," Sweetman wrote in 2015.

In 1992, after the end of the Cold War, Sweetman learned from a Tupolev fact sheet that the Tu-22M carried 54 tons of fuel—his calculations had been accurate within eight percent. Sweetman also found out from the McDonnell Douglas engineer that his team had been doing the analysis for the CIA and had come up with similar numbers. According to the engineer, Major General Keegan had threatened to interfere with McDonnell’s contract to supply the F-15 fighter to the Air Force unless the team changed its numbers. CEO Sanford “Sandy” McDonnell refused to buckle to Keegan’s pressure. Thus, while Clark may be correct that the longer Backfire range estimate was the result of “mirror imaging” and “worst-case estimation,” political pressure from the military was also a factor.[25] Sweetman concluded with a lesson: “Sometimes senior officers stretch the truth until it breaks. But the calculator tells no lies.”

The F-14 Tomcat was built to protect American aircraft carrier battlegroups from attack by Soviet long-range strike aircraft like the Backfire. Equipped with AIM-54 Phoenix missiles, the goal was to shoot down attacking aircraft before they could launch their missiles. Here an F-14 escorts a Backfire during the Cold War. (credit: US Navy) |

In 1976, the Air Force had determined the Backfire’s range at 5,400 nautical miles (10,001 kilometers), a figure that the service had stood by for several years. The Central Intelligence Agency and State Department had calculated the Backfire’s range as 3,525 to 4,150 nautical miles (6,528 to 7,686 kilometers). After the end of the Cold War, the Backfire’s actual range became known: 3,700 nautical miles (6,800 kilometers, or 4,200 miles), or very close to the CIA’s lower-range estimate.

| The Backfire serves as a case study of what President Dwight D. Eisenhower had warned about: the military services would interpret intelligence data to their advantage, exaggerating Soviet capabilities to justify larger budgets and new weapons systems. |

As more Backfires entered service, satellite reconnaissance revealed where they were based and who operated them. It became clearer that they were not being deployed as strategic bombers, nor was the Soviet Union building up its fleet of aerial tankers. Many of the Backfires were devoted to maritime attack, carrying big missiles to try and sink American aircraft carriers, using the high speed that they were capable of. Other US satellites, like the Defense Support Program missile warning satellites, were used to track Backfires and their missiles—so-called “slow walker” targets—in order to warn the US Navy. The US Navy had F-14 Tomcat fighters with long range AIM-54 Phoenix missiles to try and shoot down Backfires before they could launch their missiles.

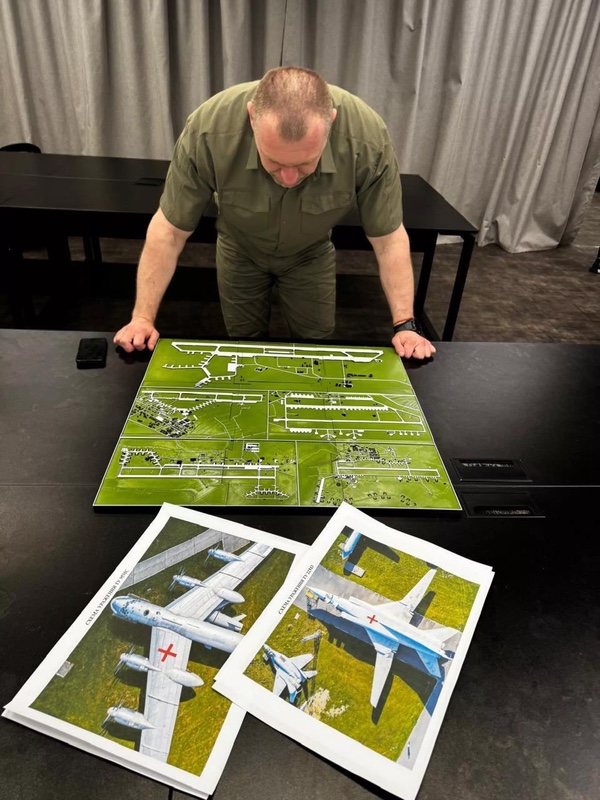

A Ukrainian general looking at photos of a Russian airfield and overhead photos of bombers, including a Backfire with an X designating the most vulnerable spot for a drone attack. Ukraine had a Backfire in a museum that it could study. (credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

Hindsight

The Backfire serves as a case study of what President Dwight D. Eisenhower had warned about when establishing the CIA’s role in overhead reconnaissance from aircraft and satellites: that the military services would interpret intelligence data to their advantage, exaggerating Soviet capabilities to justify larger budgets and new weapons systems. It was for this reason that Eisenhower wanted civilian control not only of intelligence interpretation, but also collection.

In the 1990s, Ukraine agreed to scrap almost all of its approximately 60 Backfire bombers in return for U.S. guarantees that it would protect the country from Russian attack, a guarantee the United States reneged on. (credit: Defense Threat Reduction Agency) |

At the end of the Cold War, Ukraine had 60 Backfire bombers and destroyed almost all of them, preserving a few for a museum. Russia’s current inventory is unknown, but has clearly dwindled due to age, attrition, and warfare. Prior to Operation Spider’s Web, during over three years of war, Ukraine claims to have destroyed four other Backfires and damaged six more. The Russians, of course, dispute these numbers. The CIA probably has the best estimates.

Additional reading on Team B:

Richard Pipes, “Team B: The Reality Behind the Myth”. Commentary Magazine. 82 (4) (1986).

William Burr and Svetlana Savranskaya, eds. “Previously Classified Interviews with Former Soviet Officials Reveal U.S. Strategic Intelligence Failure Over Decades”. Washington, DC, September 11, 2009.

Anne Hessing Cah. “Team B: The trillion-dollar experiment”. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 49 (3) (April 1993). Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc.: 22–27.

Thom Hartmann, ”Hyping Terror For Fun, Profit - And Power”. Commondreams.org. December 7, 2004

Melvin A. Goodman, “Righting the CIA,” The Baltimore Sun, November 19, 2004.

Additional reading on the contemporary debate over Backfire numbers and range:

Tad Szulc, “Soviet Said to Fly Big New Bomber,” The New York Times, September 5, 1971.

Bernard Gwertzman, “Kissinger, After Senate Briefing, Calls Criticism of Arms Accord Surprising,” The New York Times, December 5, 1974.

“New Soviet Bomber Reported in Service,” The New York Times, January 22, 1975.

John W. Finney, “U.S. Says Soviet Deploys Bomber,” The New York Times, October 10, 1975.

Leslie H. Gelb, “Pact With Soviet on Missile Curbs Reported in Peril,” The New York Times, October 16, 1975.

Leslie H. Gelb, “Soviet Reaffirms Stand on Arms Limit,” The New York Times, November 8, 1975.

Bernard Gwertzman, “Kissinger Voices Irritattion at Soviet on Arms Talks,” The New York Times, November 11, 1975.

“President Finds Continued Snags in Arms Parleys,” The New York Times, November 27, 1975.

Bernard Gwertzman, “Soviet Proposes Plan to Rexolve Arms Pact,” The New York Times, January 24, 1976.

Christopher S. Wren, “Soviet Delay Seen on Arms Proposal,” The New York Times, March 22, 1976.

Bernard Gertzman, “U.S.-Soviet Arms Talks are Deadlocked,” The New York Times, April 11, 1976.

“U.S. Says Russia is Arming More Missiles With MIRV’s.” The New York Times, July 30, 1976.

David Binder, “U.S. Aide Accuses Soviet on New Missile,” The New York Times, September 1, 1976.

John W. Finney, “Air Force Rebuilds its Bomber Defense,” The New York Times, November 21, 1976.

“Arms Talks Stalled Since March,” The New York Times, January 25, 1977.

Bernard Gwertzman, “A New SALT Pact: The Last 10 Percent is the Most Difficult,” The New York Times, January 30, 1977.

Hedrick Smith, “Vance is Expected to Sound Out Soviet on Key Cuts in Strategic Arms,” The New York Times, March 17, 1977.

“U.S.-Soviet Proposals on Arms Cuts,” The New York Times, March 31, 1977.

Drew Middleton, “Three Arms Development Options Seen for Carter,” The New York Times, April 1, 1977.

“Technical Issue in Arms Proposal Stirs Controversy in Washington,” The New York Times, May 3, 1977.

Bernard Weinraub, “Russia’s Backfire Bomber; Red Threat or a Red Herring?” The New York Times, May 7, 1978.

References

- The Russians referred to the area as Zhukovsky.

- National Photographic Interpretation Center, “Backfire Production From 1969 to Mid-1983, USSR,” August 1983, p. 1. Although the exact date of the first observation remains classified, the report indicates on page 5 that the first observation was in August 1969. The two reconnaissance missions active during this period were CORONA mission 1107 early in the month, and GAMBIT mission 4323, late in the month.

- National Photographic Interpretation Center, “Backfire Production From 1969 to Mid-1983, USSR,” August 1983, pp. 1-2.

- National Photographic Interpretation Center, “Backfire Production From 1969 to Mid-1983, USSR,” August 1983, p. 4.

- Major General George J. Keegan, Jr., Assistant Chief of Staff (Intelligence), to William E. Colby, Director, Central Intelligence Agency, October 9. 1973. CIA-RDP80R000800140031-1

- Deep Black: Space Espionage and National Security, Random House, 1987, p. 8.

- Ernest J. Zellmer, Associate Deputy Director for Science and Technology, Memorandum for Director, “OWI Comments on General Keegan’s Message re Backfire Analysis,” August 6, 1976, with attached: “Comments on Air Force Review of CIA Backfire Analysis,” August 5, 1976. CIA-RDP79M09467A0025080017-9.

- Brig. Gen. Lew Allen, Jr., to DNRO (Dr. McLucas), “Quarterly Program Review for January 1, 1971 through March 31, 1971,” May 20, 1971. C05098695

- Director of Central Intelligence George Bush, to Brent Scowcroft, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, “CIA Analysis of Backfire,” August 11, 1976. CIA-RDP79M00467A002500080015-1. The press leak is mentioned in a cover memo.

- Director of Central Intelligence George Bush, to Major General George J. Keegan, Jr., Assistant Chief of Staff, Intelligence, USAF, “BACKFIRE,” August 24, 1976. CIA-RDP79M00467A002500080012-4.

- [Deleted], USN, PAID, Memorandum for Deputy to the DCI for the Intelligence Community, “BACKFIRE,” August 17, 1976, CIA-RDP83M00171R000700330002-3

- [Deleted], USN, PAID, Memorandum for Deputy to the DCI for the Intelligence Community, “BACKFIRE,” August 17, 1976, CIA-RDP83M00171R000700330002-3

- [Deleted], National Intelligence Officer for Strategic Programs, Memorandum for the Director, “The Soviet Backfire Bomber: A Chronology of CIA’s Reanalysis,” October 13, 1976, CIA-RDP79M0067A002500070008-9.

- Foreign Relations, 1969–1976, Volume XXXV, Department of State, 2014, pp. 789-790.

- Foreign Relations, 1969–1976, Volume XXXV, Department of State, 2014, pp. 789-790.

- Howard Stoertz, Jr., National Intelligence Officer for Strategic Programs, Memorandum for Director of Central Intelligence, “Suggested Response to Possible Questions about Backfire Performance on ‘Face the Nation,’” March 18, 1977, CIA-RDP80M01048A001100200023-5

- CIA Memorandum for the Intelligence Advisory Committee, “Validity of Heavy Bomber Estimate in NIE 11-4-57.” CIA-RDP61-00549R000200010002-1

- National Photographic Interpretation Center, “Backfire Production From 1969 to Mid-1983, USSR,” August 1983, p. 5.

- Deep Black: Space Espionage and National Security, Random House, 1987, p. 8.

- Brigadier General David D. Bradburn, Note for General Allen, “SALT and NRP Systems,” October 16, 1972, with attached: Major Harold S. Coyle, Jr., Memorandum for General Bradburn, “SALT and System Improvements,” October 11, 1972, and: Brigadier General David D. Bradburn, Note for SS-5, Major Coyle, “SALT and System Improvements,” October 16, 1972.

- Deep Black, p. 14.

- Robert M. Clark, Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach, Fifth Edition, 2016, pp. 159-161.

- “Production Backfire Flies From USSR,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, January 3, 1977, p. 21.

- Bill Sweetman message to author, July 6, 2025.

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/though-a-glass-darkly-bill-sweetman-technically-speaking-column-180957300/

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.