The American Spectator fails the Mars testby Taylor Dinerman

|

| The Bush plan is based on two political facts: no President or Congress is going to give up on human space exploration, and NASA is never again going to get more than one percent of the federal budget. |

As long as NASA was not allowed to seriously plan for manned missions beyond LEO, it had every incentive to protect its monopoly on US human spaceflight. When in April of 2001 Dennis Tito became the first American to go into space without asking NASA’s permission, the agency was not at all happy. From then until January 2004 they grudgingly came to accept that Russia was going to fly paying passengers to the ISS. When the President gave them a new set of marching orders the bureaucratic need to protect their turf was no longer a factor, and since then they have been far friendlier to entrepreneurs than ever before. NASA is still a government agency with all that it implies, but it is, at least, now willing to get out of the way of US private enterprise.

For conservatives and libertarians NASA looks like a big government agency and thus is automatically suspect. Liberals and leftists think of it as an extension of the military industrial complex and, thus, inherently undesirable. It should go without saying that both groups are somewhat correct. NASA is, to put it bluntly, an instrument of American national power. This may be why it finds it easier to deal with the Russians and Japanese, who understand and believe in the nation-state, than with ESA, which is ideologically hostile to national sovereignty. The US civil space program serves national goals by keeping America in the forefront of space exploration, technology, and science.

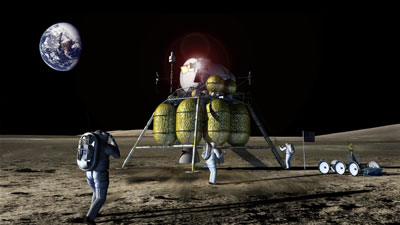

More important, it lays down a marker outside Earth’s atmosphere that says to the other nations of this planet, “We are here and we are going to dominate. Others are welcome to join us but we are going to be the top dog out here.” This claim can only be made if there are real live Americans out there on the Moon and eventually Mars. Cute little robots are acceptable as precursors, but only humans can make the claim that “We came in peace for all mankind,” as the plaque Apollo 11 left on the Moon says.

The case for NASA is a nationalistic one, and while our friends on the left would have us believe that this is a dirty word, some on the right dislike it, too. The enduring popularity of the idea, if not the term itself, is due to the fact that people tend to put the needs of their fellow citizens first. This is a case where Congress “gets it”. Last year’s NASA authorization bill boldly states the aim to “advance US scientific, security and economic interests though a robust space exploration program.” This goal is closer to the aims of the Eisenhower-era interstate highway system, which was in part a national defense project, than to the LBJ’s “Model Cities” programs or other manifestations of the welfare state.

| The case for NASA is a nationalistic one, and while our friends on the left they would have us believe that this is a dirty word, some on the right dislike it, too. |

One happy surprise is the way the President’s science advisor, John Marburger, has, as far as one can tell, been serious about putting American interests ahead of those of the international community or other vaguely defined and unaccountable entities. At last month’s Goddard Symposium Marburger made the point that “The ultimate goal is not to impress others, or merely to explore our planetary system, but to use accessible space for the benefit of humankind. It is a goal that is not confined to a decade or a century. Nor is it confined to a single nearby destination, or to a fleeting dash to plant a flag. The idea is to begin preparing now for a future in which material trapped in the sun’s vicinity is available for incorporation into our way of life.”

To put it another way, the Bush vision, if sustained, will ultimately lead to a situation where the US will not depend for its raw materials and energy on unstable places like the Middle East or Central Africa. It may take a long time and require a substantial investment, but it will ultimately keep the US at the top of Earth’s economic and geopolitical food chain well into the 22nd century.