US-China space cooperation: the Congressional viewby Jeff Foust

|

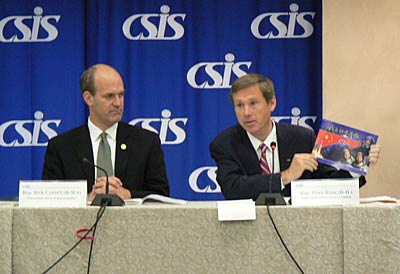

| Unlike the White House or the Senate, “the House view towards China is relentlessly negative and highly misinformed,” Kirk said. |

The formation of the US-China Working Group was linked to Congressional debate about the proposed acquisition of oil company Unocal by a Chinese state-owned company, CNOOC. That debate, Kirk said, was laced with inaccurate information about CNOOC and China, creating enough controversy that CNOOC was eventually forced to withdraw its bid. “It is perfectly acceptable to criticize China when you have a correct means,” Kirk said. “What we are against is uninformed criticism, which is largely what I regard as dominant on the House floor today.”

That “uninformed criticism”, Kirk said, causes the House to stand apart from both the Senate and the White House. “I’ve characterized the White House view towards China as nuanced and complex. The Senate view towards China is at least multifaceted, with some ups and some downs. And the House view towards China is relentlessly negative and highly misinformed.”

One way the working group is trying to improve overall perceptions about China in the House is through better understanding, and potentially cooperating with, China’s space program. However, this is an area that Kirk believes requires a lot of outreach to his colleagues. “My take on the House of Representatives floor right now,” Kirk said, “is if I said that China had a very active manned space program, that would still be news to a lot of my colleagues… I think this entire field is one in which the Congress is largely unaware.”

Improving that “highly misinformed” view of their colleagues is a major challenge, Larsen, a Democrat from north of Seattle, admitted in comments after the CSIS forum. He said the working group has plans to work together with the Congressional Space Caucus to help meetings and discuss space policy issues. As for near-term successes, Larsen noted that people on the Hill are talking about the concept of common docking adaptor, a device that would allow the shuttle and/or CEV to dock with China’s Shenzhou spacecraft, an idea that was raised on Kirk and Larsen’s trip to China earlier this year.

Cooperation and competition issues

Kirk and Larsen singled out China’s manned space program as a major avenue for any potential competition. The concept of a common docking adaptor stems from a desire to provide an on-orbit search-and-rescue capability, so that one country’s vehicle could rescue the other country’s stranded crew in the event of an accident. “I think the manned space program has a potential all out of proportion to its size and cost for improving the diplomatic, political, and military atmosphere between the United States and China,” said Kirk.

| “There are a lot of folks who are looking for grabbing the thousand-dollar bill instead of trying to pick up nickels and dimes in the relationship with China,” Larsen said. |

Larsen said that the working group was developing an agenda of issues for NASA administrator Mike Griffin to discuss with Chinese officials when he travels to the country in September. Such issues range from a common docking adaptor to scientific exploration and orbital debris tracking. Another “highly symbolic” but important thing Griffin could do, he added, would be to meet with Fei Junlong and Nie Haisheng, the two Chinese astronauts who flew on the Shenzhou 6 mission last year. Kirk even suggested that the US ask China to loan the Shenzhou 6 capsule to a US museum.

The general theme of these proposals were their relatively small scale, rather than much larger initiatives like Chinese participation on the International Space Station or joint lunar exploration, an emphasis that Larsen said was deliberate. “There are a lot of folks who are looking for grabbing the thousand-dollar bill instead of trying to pick up nickels and dimes in the relationship with China,” he said. “If China sees our relationship as really long term, we may want to as well, and focus on picking up nickels and dimes along the way in order to build up to a place where we can grab that thousand-dollar bill, grab the big prize, whatever that prize is in terms of our relationship with China and theirs with us.”

The discussion about cooperation brought up an interesting point, though. Larsen noted that while China may be interested in cooperating with the US, it is not waiting on us, noting the various cooperative efforts China has in place with other countries, ranging from Europe to Brazil. “I think it ought to force a discussion in the US among policymakers about what our approach to China and space will be since they are cooperating with others, they are not waiting for us to cooperate, and they have put people into space,” he said.

What becomes less clear, though, is how China wants to cooperate with the US, and why. “What struck me the most is that there is a lot of talk about it would be in the US interest to cooperate with China, but that’s kind of where it ends,” Larsen said. “To have our potential competitor or potential partner say it’s in our interest doesn’t mean it’s in our interest, and we need to do a better job of defining our own interests.”

Inevitably, when the issue of cooperation with China comes up, so does the concept of competition: that China might be racing the US back to the Moon, for example. Neither Kirk nor Larsen, though, saw much of a race between the two nations. Speaking about China’s manned spaceflight program, Kirk noted that “my sense is it’s slightly slowed despite the technical prowess and achievement and the PR attention put on the program. The tangible transparent financial commitments by the central government of China to the space program could be larger than they are and so I have got some sense that the momentum on the civilian side is not as big as it could be.”

Or, as Larsen put it: “I don’t know that we’re in a space race with China. If this thing is a marathon, we have got 385 yards left and they are still at the starting line.”

The two made it clear that while US perceptions of China need to change for cooperation between the two on space issues to grow, there also needs to be changes in how China runs its space program, particularly the role of the People’s Liberation Army. “We’re just not sure who runs it and who sets the policy,” Larsen said.

| “I don’t know that we’re in a space race with China,” said Larsen. “If this thing is a marathon, we have got 385 yards left and they are still at the starting line.” |

“I think one of the things that would be necessary is a vast upgrade in the transparency of the Chinese civilian space program, its budget, its operation, its command, and its direction,” Kirk said. “Over the long haul, if China had an entirely civilian space agency that was completely run and administered and even guarded by a civilian agency, that would improve potential for cooperation an international context.”

Inevitably, any China-US space cooperation will get tangled up in bigger issues between the two countries, like economic policy and human rights, something that the congressmen said shouldn’t be avoided. “The fact is when you talk to the United States you have to talk democracy and human rights; it’s just part of who we are. We’re going to talk jobs, and we’re going to talk about the economy. We’re going to talk about military issues,” said Larsen. “They may be uncomfortable to talk about, but we’re going to have to address these issues if we’re going to even get to a point where we can talk about moving forward.”

This gets back to the question of what each country has to gain by cooperating with one another in space exploration, an issue that arguably has not yet been convincingly answered in either country. Larsen, looking at the big picture, notes that China is working hard on a number of fronts to become more technologically advanced. “The space program is part of that economic development goal,” he said. “US policy needs to understand that, address it, and find ways to engage China on any number of issues because that country is thinking more strategically in terms of goal of competitiveness than I think we are.” How space fits into that big picture—or even if it does—has yet to be determined.