Lies, damned lies, and cover storiesFrom Cosmos to ZaryaIn contrast to the Americans, the Soviet Union chose to impose an even more extensive security program on their space launches. Since 1962, the Russians, and the Soviets before them, have launched over 2,400 satellites under the “Cosmos” designation. The most recent, Cosmos-2423, was launched on September 14, 2006 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Beginning with the first Cosmos launch, the Soviets typically issued generic statements for every mission: they would announce the launch date, the initial orbital parameters, and a vague sentence noting that all systems were functioning properly. For most Cosmos missions, this was all that was officially revealed. Early Western observers of the Soviet space program—such as the Congressional Research Service’s Charles Sheldon and the British analyst Geoffrey Perry—very quickly determined that these hundreds upon hundreds of generic Cosmos spacecraft, about which the official Soviet news agency had little to say, were in fact military missions. By carefully observing their orbital behavior, Westerners were able to accurately conjecture the actual missions of these satellites, such as photoreconnaissance, radar reconnaissance, anti-satellite, communications, and navigation. Sheldon, Perry, and others also identified many missions as being test vehicles for manned spacecraft or failed deep space missions.

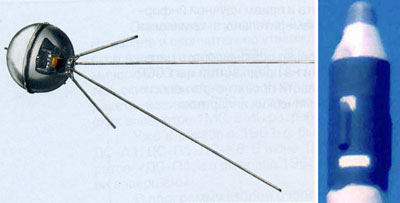

While it is clear that the Soviets used the Cosmos label as a way to obscure the military dimensions of their space program, until now, there has never been any hard evidence revealing Soviet thinking on how they tried to hide their military and intelligence satellite programs. Archival documents declassified earlier this year finally and conclusively show that the Soviet government engaged in deliberate attempts to deceive the West about the true nature of the Cosmos program. In the earliest days of the space age, the Soviets had an almost peculiar attitude to naming spacecraft. For example, most people nowadays know the first Soviet satellite, launched on October 4, 1957, as Sputnik. In truth, in the original announcements for Sputnik, the Soviet press did not even give the satellite a name, generically calling it the “first Soviet artificial satellite of the Earth,” which is what Russians still call the world’s first satellite. Because the Russian word for “satellite” is “sputnik”, the latter name stuck in the West. Similarly, when they launched the first lunar probes in the late 1950s, the Soviet press imaginatively called them “the first space rocket” or “the second space rocket,” and so on. This almost indifferent policy of naming spacecraft stemmed partly from the newness of the space program. In the late 1950s, the Soviet space program—which emerged from the Soviet ballistic missile program—was still in its infancy. Most space program managers were literally inventing new conventions to understand a whole new generation of technology. Naming a spacecraft became a more important issue in the early 1960s when the Soviet space program began to expand into many different areas—manned programs, deep space missions, scientific satellites, etc. When cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space, the Soviets introduced their first official designation, “Vostok” (“East”) used for their first-generation manned space program. Later names such as Mars, Luna (“Moon”), Polyot (“Flight”), Elektron (“Electron”), Zond (“Probe”), Voskhod (“Rise”), Proton, Molniya (“Lightning”), and Venera (“Venus”) joined the ranks by the mid-1960s. Yet, as launch rates in the Soviet space program exploded by the late 1960s, one program, under the Cosmos label, remained strikingly opaque. When the first in the Cosmos series was launched on March 16, 1962, the official TASS press agency announcement included a long list of scientific goals of the program, most having to do with upper atmospheric research. The official communiqué ended with the claim that because of the new program, “Soviet scientists will have new opportunities to investigate the physics of the upper layers of the atmosphere and space.” Newly declassified documents show that scientific research wasin fact the original mandate of the Cosmos program. When a modest program of upper atmospheric research was preparing for launch, in October 1961, the government decided to group the new satellite project under the new Cosmos label. In the same decision, space program bureaucrats decided that the Cosmos label could also be ideal for grouping other new programs which were about to begin—particularly a sensitive and secret photo-reconnaissance intelligence satellite secretly known as Zenit-2. Documents from the period show that that this was a deliberate policy, i.e., that “…along with scientific satellites, with the goal of camouflaging Cosmos satellites, all satellites delivered into orbit with military goals… were named in these TASS announcements.” Slowly, the Cosmos label became a useful umbrella for any “inconvenient” satellite. For example, in late 1962 and early 1963, the Soviets launched several deep space probes, most of which failed and were stranded in Earth orbit. They kept silent about these launches, hoping no one would mention them. American radars, however, clearly tracked the objects in orbit, and their existence was publicized in the New York Times as failed Soviet space missions. As malfunctioning spacecraft accumulated in orbit, under pressure to register all their launches with the United Nations, and trying to avoid further publicity, in late 1963, the Soviets decided to group failed deep space probes under the Cosmos label, beginning with a failed lunar flyby vehicle which was named Cosmos-21. The Cosmos cover story had only limited effectiveness, however. By late 1964, Western observers began to suspect that some Cosmos spacecraft had at least some reconnaissance missions. They began to publish articles that questioned the Cosmos designation.

By 1965, after the launch of about ninety Cosmos satellites, Soviet military officials discovered something that their American counterparts had already learned—that there was a difficult tradeoff between how much to obscure and how much to reveal. Also like the Americans, they learned that creating scientific cover stories for programs created expectations within the scientific community that could gradually become problematic for the military. By this time, the Soviets had introduced or were about to introduce several new military and intelligence systems for testing in orbit, including for signals intelligence, navigation, geodesy, ocean reconnaissance, and improved reconnaissance satellites. This large increase in satellites would stretch the scientific cover story to its limit. In October 1965, the Soviet government acknowledged in a secret memorandum that: “the launch of these objects and programs of their work do not always agree with the volume of program published by Tass on March 16, 1962 [in connection with the launch of the first Cosmos satellite], making it difficult to explain in print and at international meetings that all of these launches of the Cosmos… are only for the solution of scientific goals.” Some of these satellites were indeed scientific and their results were publicly announced. But now there would be a significant expansion of the military program, and Cosmos numbers would explode. There would be many satellites that would be conspicuous by the absence of any announced results. The Soviets were also very sensitive to the notion that Westerners would identify the whole Cosmos program as a cover for military or intelligence activities. How could the Soviet government continue to claim that the Cosmos series was only for scientific goals when they were hardly announcing any of the results of the Cosmos missions in public? They needed a way to keep the military program completely under wraps, deceive Westerners, and maintain the fiction that the program was dedicated to scientific research. To solve this problem, the Soviets decided to introduce a new series known as Zarya, the Russian word for “dawn”. In a letter attached to the secret memorandum that was addressed to the Communist Party’s Central Committee, leading Soviet space program officials, including the chief of the General Staff Marshal Matvey Zakharov and the Chairman of the KGB Vladimir Semichastnyy, underscored that the Zarya series would include many of the same classes as Cosmos. For example, future failed Soviet satellites would be grouped under the Zarya label. Critically, they noted that, as far as: “announcements for the launches of military satellites, [including both those operational] and those newly developed, it would be advisable to publish [them] under [both] the Cosmos and Zarya programs, with the view that one and the same satellite could be published under one or the other program.” In other words, the Soviets would launch military satellites under both the Cosmos and Zarya designations, randomly assigning names with no rhyme or reason. The authors of the letter were candid about their objectives: their primary goal was to introduce a system that “would further camouflage military objects [in space].” According to this plan, officially the Soviets would explain to the world that the new Zarya series was for much nobler goals, specifically testing of five systems: launch vehicles, spacecraft control systems, communications systems, life support systems for living organisms, and reentry and landing systems. According to the public announcement, all of these goals would be “an important stage in ensuring the future study and mastery of cosmic space.” There would be, of course, no mention of any military goals.

Sometime soon after this proposal of disinformation, the Soviets dropped the Zarya plan. In the end, they chose to retain the singular Cosmos label for all military, test, and failed spacecraft, as well as many scientific satellites. Why did they not adopt the Zarya plan in 1965? There is no firm evidence to suggest why, but circumstantial evidence suggests that at the end of the day, Soviet authorities decided that a single all-encompassing label such as Cosmos was better than two different programs. They believed that running two programs such as Cosmos and Zarya would give Westerners more weapons to argue that the Soviets were running two major military programs. More important, as the Soviets began to figure out secret American military and intelligence missions in space through observing orbital behavior, they recognized that the Americans could do the same for the Soviets. Trying to “camouflage” military satellites through multiple designations would provide marginal and perhaps ultimately no advantage while creating another mound of red tape. The Soviets stuck with the Cosmos label. Since the Soviet times, much has changed. The Russians now announce every single launch in advance. And when they launch military satellites, although they do not describe specific missions, they actually issue a short statement that “the satellite was inserted into orbit in the interests of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation.” Most ironically, the Cosmos label has itself become a rubric which Soviet bureaucrats in the past could have hardly imagined: because nowadays all civilian satellites (including those that fail) have their own independent designations, one way to identify whether a Russian satellite has a civilian or a military objective has become easy. If it has a Cosmos name, it is most certainly a military satellite. If it doesn’t, it is probably a scientific or commercial satellite. The Cosmos name has finally become the exact thing the Soviets never wanted it to become: it has become completely predictable. Home |

|