Promising the Moonby Greg Zsidisin

|

| Bush deserves credit for making such a strong statement about space, and working with NASA administrator Sean O’Keefe to develop a considered plan. |

However, the new plan’s many vagaries, challenges and questions leave advocates little on which to hang their hats, and plenty of opportunity for critics to charge that the plan would lead to massive new expenditure. That’s in part a case of the sins of the father: the $400 billion suggested retail price of the 1989 space plan is now being routinely inflated to $1 trillion in the press.

Let me list a few of the many questions the new plan raises, and the challenges it will face:

- Assuming this administration works at—and succeeds in—raising Congressional and public support, how long would this program continue after the Bush presidency? By 2008, the end of a potential second Bush term, the new Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV) is to have been flight tested, and new robotic lunar missions are to have begun. It would be easy to stop the program after that, keeping the CEV for the ISS crew transport role only.

- What other programs will be scavenged for NASA to focus on this? Under the plan, shuttle expenditures won’t end until FY 2011, while the ISS budget continues until FY 2017. The proposed five-percent yearly increase in NASA’s near-term budget will essentially cover the cost of the new lunar robotic exploration, but getting the CEV to flight testing will likely require more resources than those now available in the OSP program, especially considering that vehicle’s estimated price tag of about $10 billion.

- How does the new CEV program dovetail with the Orbital Space Plane project, which is presumably canceled under this plan? Are we (once again) back to square one in designing a shuttle successor which must now be capable of lunar missions as well? Given the stated missions, and less than five years to get flying, a reinvention of the Apollo Command/Service Module seems likely.

- Some aspects of the plan require real leaps of faith. The White House suggests that space vehicles will eventually be launched from the Moon, having been built there from lunar raw materials. How would we move from having astronauts doing Antarctic-style visits around 2015, to that kind in-situ manufacturing?

NASA will need to operate differently if this new program is to be truly affordable, stay within the prescribed budget, and become the gateway to human expansion into space that President Bush rapturously described. The new imperative must mean a new NASA, far more open to innovation and outside input. That is a battle yet to be fought.

There are age-old proposals for making the maximum use of existing resources and technology, which NASA should seriously review. This should mean everything from adapting ISS designs for lunar habitats and hardware to placing shuttle external tanks in orbit on shuttle flights. The tanks could be ferried to the Moon carrying their residual propellants (from which water can be derived), and might even be used as habitat structures after they have arrived.

Tether technology could play a key role in the new space program. Tethers Unlimited, Inc. (TUI) has postulated a cislunar transportation system in which two long rotating tethers, one in Earth orbit and the other in lunar orbit, would regularly move payloads between the Earth and the Moon without propellant. TUI claims the system could be made using existing materials. Surely tether technology deserves a serious examination now.

Probably the most important technology to reuse is that of the shuttle program. There is far too much growth potential, investment and infrastructure now in place to simply retire along with the shuttle orbiter. Any affordable space program would make the most possible reuse of shuttle systems, lest we repeat the mistake of Apollo and choose to scrap everything, only to expensively start from scratch.

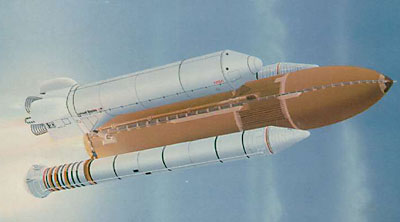

At a minimum, NASA should dust off its own work on Shuttle-C, which replaces the orbiter with an engined cargo module to deliver large amounts of payload to orbit. Shuttle-C work was well along at Marshall Space Flight Center when the project was canceled in 1992. Especially with the current availability of large expendable engines, Shuttle-C—or another shuttle-derived vehicle, such as Buzz Aldrin’s Aquila or my own Shuttle-B—should be high on NASA’s list.

| Probably the most important technology to reuse is that of the shuttle program. There is far too much growth potential, investment and infrastructure now in place to simply retire along with the shuttle orbiter. |

The agency would also need do more to bring innovative space startup companies into the picture. It could begin simply by using the Assured Access to Station program (formerly Alternate Access to Station) to nurture more small companies trying to get into the launch field, especially in ISS resupply and crew transfer, before and after the shuttle is retired. More importantly, it means making room for these small companies among the aerospace giants.

The Columbia disaster and resulting accident report were the triggers and overriding influences for this new plan; that timing was what it was. However, if there is an acid test for human spaceflight, it is surely making a proposal like this on the heels of racking up a record budget deficit, with two simultaneous foreign wars and the constant threat of terrorism in play. It is hard to imagine a more difficult time for the case for human spaceflight to come onto the national agenda.

We are now at a moment of truth. Will a new, vigorous space program, with sufficient support, emerge in the coming year? Or will space supporters need to wait another 15 years after the second Bush space plan to try again?