Space: the search for a political consensusby Frank Sietzen, Jr.

|

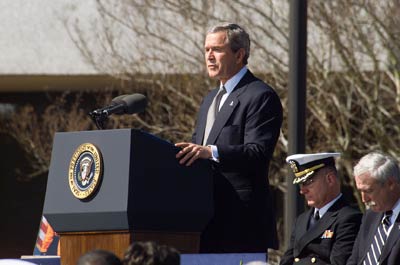

| For many of us George W. Bush’s silence in neither explaining nor defending his Vision for Space Exploration is not surprising. What propelled the Bush administration to set in motion the series of interlocking policy decisions that became known as the Vision was neither interest in space nor a systematic review of federal science policy. |

But once that consensus had been crafted the question remained as to how to pay for it. The retirement of the Space Shuttle, and with it a freeing up of the approximately four billion dollars a year NASA spends on it, was the key element in funding the Vision. Bush made it clear to Sean O’Keefe that any major new space initiative could not expect major new federal funding. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board was calling in the summer of 2003 for recertification of the Shuttle fleet if NASA was to continuing flying them, a process that few knew how to conduct. The primary justification for the Shuttle being completion of the ISS, it made political sense to retire the Shuttle once the station was completed and then shift its funds to supporting development of what would become the Crew Exploration Vehicle. The date of 2010 was chosen as what planners then thought was the earliest the station could be built, but also behind the scenes many believed that this date was fungible—and was more likely to be 2012. The problem facing O’Keefe was that every year the Shuttle continued in operation was a year delay in the development of the Constellation vehicles. In late fall 2003 O’Keefe managed to wrangle a few billion in additional funding from OMB and, along with Shuttle retirement funding made available, would be what we might call “earnest money” to start Project Constellation. But NASA itself had to change. As Keith Cowing and I said in our book New Moon Rising and as Courtney Stadd has so wisely stated, without that transformation NASA would not only be unable to accomplish the goals of the Vision, but with the advent of new commercial space systems, risked becoming irrelevant. That blueprint for transformation, crafted by the Aldridge Commission in June 2004, has largely been forgotten.

What was not clear in 2004 but is clear today is that arbitrary date of Shuttle retirement in 2010 truncates the completion of the station. The definition of what a completed station would be has morphed. Without the lifting capability of the Shuttles, which is not duplicated by the Orion vehicles, already completed station components, such as the Japanese centrifuge module, will remain on the ground. Maintenance of the station must also be reshaped, with many replaceable components that were designed to be returned to Earth on the Shuttle to be refurbished and flown back now being literally tossed over the side of the orbiting outpost and new units built to replace them. On paper, at least, the station itself is to be decommissioned in 2016, meaning the full compliment of a six person crew will get exactly six years of work before the entire machine is destroyed in reentry. With Congress’ action to declare the station a national laboratory last year, and with new initiatives to find other government users for the station, hopefully that date will be pushed back even further. There seems to be a broad political consensus in the Congress to support the completion of the station and its use in addressing life science research. No rationale for constructing a lunar base can be made, it seems to me, without a full use of the investments the nation has made in the ISS since President Reagan made it a national goal in January, 1984, more than 20 years ago.

It also seems to me that we need some perspective. The Vision for Space Exploration was established at a time of record deficits, when America was conducting one war against terror in Afghanistan and another in Iraq. The war in Iraq is costing Americans two billion dollars a week. This president has shown no interest in either science or space, and is the head of a political party many of whose members doubt the veracity of evolution and climate change. Given these political realities it is surprising not that the Vision has its flaws, but that Bush set forth a space vision at all.

| If we wish to craft any enduring political consensus that lasts, one strong enough to form the basis of any future president’s space policy, then it is clear that a lot of educating of the average citizen must be done. |

Then there is the issue of what value does the public—and by osmosis the president—place upon space activities. I have spent much of the past year completing a book that profiles some of the products, services, and technologies derived from space exploration (no, they do not include Velcro or Tang). I have been astonished by the variety of such products, and how little the public knows of their space technology origins. In an earlier age, these were collectively called spinoffs, and often derided by space enthusiasts as rationales for conducting space flight. However, they are enormously popular with the average American. Recently, NASA conducted a series of focus groups to gauge the basis for public interest in their activities. That research found that messages that focus on a specific plan for the future of space exploration is more popular than any one specific mission or destination in space. Furthermore, the groups told NASA that when the benefits of space are fully explained to them, 94 percent of the public believes NASA’s work is extremely or somewhat relevant to their lives—up from 53 percent when space benefits are not explained (see “NASA’s new outreach plan”, The Space Review, July 2, 2007). And while half of the public (in February 2007) had heard about astronaut scandals, only eight percent knew about the details of going back to the Moon or journeying onward to Mars.

If we wish to craft any enduring political consensus that lasts, one strong enough to form the basis of any future president’s space policy, then it is clear that a lot of educating of the average citizen must be done. The broadest such consensus can most likely be built around a civil space program that neither shortchanges Earth or space science or long-term human exploration. Lori Garver is quite right to express concern about cuts to NASA’s basic science missions, cuts that the Congress has moved to recently restore in part. My friend Courtney Stadd is also right to express his own concerns about the deficiencies in planning for human space transportation. The more things change, it seems, the more it stays the same.

As I wrote in Space Times in the fall of 2004 America is best served by a balanced space program in which the central component is how exploration, as any other federal science program, benefits the greater good. Human exploration of space, by its very nature, will always require a disproportionate share of the federal civil space budget. I have spent much of my adult life promoting the concepts of reusability and permanence as the cornerstones of human spaceflight. The legacy of the reusable era—that of the Space Shuttle—shows policy makers both the advantages and fragility of a highly technologically advanced vehicle that pushes, perhaps too far, the state of the art. The legacy of permanence—that of the Space Station—shows planners the challenges of crafting a framework for a working consensus involving many nations in pursuit of a single space goal. Without the pitfalls of compromise or a loss of focus when the promise of a new space project comes calling.

Any review of the three previous major space initiatives—going to the Moon under Kennedy, developing a reusable space vehicle under Nixon, and a permanent station under Reagan—shows that America does not execute long-term space projects well or fund them to their ultimate completion. History is a cautionary tale for those who hope to add the Vision for Space Exploration to that limited list.

Both Shuttle and Station programs have often fallen short of their hype and history, but both have also provided our country with enormous opportunities and achievement. By working through these flawed programs and compromised machines, we have come of age in space. Soon it will be for the next president and future Congresses to reshape the Vision while hopefully preserving, not ending, the legacy of both Shuttle and Station. Given the history of American space policy it will be a challenge of evolution and renewal almost as old as our young Republic itself.