Eats, shoots, and leavesby Dwayne A. Day

|

| China has a secretive government, and a very active publishing industry, so why should we automatically assume that a tiny sample of public literature indicates what China really intends in their space weapons program? |

Christopher Stone used several similar cheap tricks in his recent article about the Chinese ASAT test (“Chinese intentions and American preparedness”, The Space Review, August 13, 2007). His first offense was malicious use of quotation marks. As Lynne Truss demonstrated in her witty book about punctuation, Eats, Shoots, and Leaves, moving a comma can have major effects on the meaning of a sentence. Fortunately, quotation marks are blunter instruments. Normally, they are supposed to indicate that certain words were spoken by a person, but they do have a few other, rather blunt uses, one of which Mr. Stone employed.

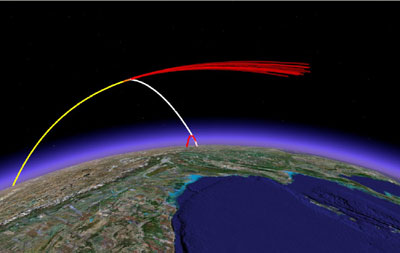

Mr. Stone wrote about the January 2007 Chinese ASAT test, which he argues has substantially changed the military threat to the United States. His article is intended to sound the alarm and warn that confrontation with the Chinese is inevitable. He used the word “enemy” several times to describe how China views the United States—perhaps this explains why they are poisoning our children’s toys?

There are a number of problems with the article, including the somewhat dubious assumption that as Stone claims, “it is easier than some think” to figure out what Chinese military leaders and government officials are planning based upon a few public Chinese documents. China has a secretive government, and a very active publishing industry, so why should we automatically assume that a tiny sample of public literature indicates what China really intends in their space weapons program? We already have an example of the dangers of drawing big assumptions from public literature, when the US military claimed that China was developing “parasitic microsatellites” based upon publicly available information that proved to be entirely fictional. As Dean Cheng of CNA Corp—which has a contract from the Pentagon to study Chinese military and space doctrine—has said in several public forums, a major problem with understanding Chinese actions and intentions is sifting through a huge volume of often-contradictory public material and determining which of it, if any, represents the views of people in power. We object when foreigners seize upon a single bombastic American document to prove that the United States is seeking space weapons, so why should we do the same thing to the Chinese? Is the objective discussion and comprehension, or mudslinging?

But I’d actually like to point to a more minor but still insidious issue. In the course of his clarion call, Mr. Stone employed an age-old trick of punctuation that betrays an unwillingness to engage in rational discourse. Mr. Stone wrote: “According to some, the intentions and reasons for conducting this test are elusive. These ‘experts’ are in a state of denial.”

Later Mr. Stone wrote: “Even though space warfare hasn’t truly happened yet, is it really wise to dismiss the open source documents from the Chinese military colleges and doctrine centers just because we haven’t seen mass attacks on our GPS constellations or other spacecraft? The experts who have put together sound analysis of the situation don’t think so and neither does this author.”

Note the difference. In the first usage, Mr. Stone puts quotes around “experts” whom he disagrees with, but in the second case he does not put quotes around “experts” whom he agrees with. Why? Unless English is your second language, the reason is pretty clear: Mr. Stone is implying that the “experts” who disagree with him are not “experts” at all. Those quotation marks are a way of saying “so-called experts” and questioning the qualifications of people that Mr. Stone disagrees with.

| We object when foreigners seize upon a single bombastic American document to prove that the United States is seeking space weapons, so why should we do the same thing to the Chinese? Is the objective discussion and comprehension, or mudslinging? |

There are many problems with this, including the fact that it is petty and underhanded to slam the qualifications of people simply because you don’t like what they say. But let’s ignore those issues for a bigger one: who, exactly, are the “so-called” experts that Mr. Stone is attacking? He doesn’t name the people he disagrees with. This does not contribute to the discussion, and in fact it allows Mr. Stone to have it both ways, to vaguely attack people whose opinions that he does not like, but then if he gets called on it, to deny that he was attacking any specific person. To paraphrase one of my personal heroes, if you’re going to shoot somebody in the back, do it while facing them—and they’re armed. It’s only polite.

Really, the last thing the Internet needs is more people with opinions and mean-spirited agendas. The Space Review should be a place for civil discourse. And proper use of punctuation.