|

|

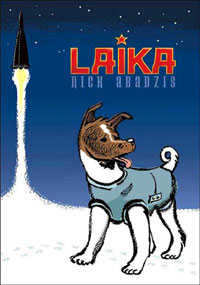

Review: Laika

by Jeff Foust

Monday, September 10, 2007

Laika

by Nick Abadzis

First Second Books, 2007

softcover, 208 pp., illus.

ISBN 978-1-59643-101-0

US$17.95

There are many ways to tell the history of the Space Age in a book: a scholarly history replete with footnotes, endnotes, and a long biography; a more streamlined approach for broader audiences, with fewer references and less academic language; biographies and autobiographies, both scholarly and popular; and graphic novels. Wait… a graphic novel? The medium has gained increased respectability and readership in recent years as it distanced itself from superhero comic books as a means to combine illustrations and the written word to tell compelling tales. That approach is used quite effectively in Laika to tell the story of the first living creature to orbit the Earth.

Most space-savvy people can summarize Laika’s story into a single sentence: a stray dog plucked off the streets of Moscow who became famous when she was launched on Sputnik 2 in November 1957, surviving for only several hours become succumbing to heatstroke (a fact that only became clear within the last decade, as details about the early Soviet space program came to light after the collapse of the Soviet Union.) Laika fleshes out the life of that dog, including details about the training and the events leading up to the dog’s launch, part of a crash program initiated by Nikita Khrushchev to capitalize on the propaganda victory of the Sputnik 1 launch.

| Laika is not meant as a substitute for a proper scholarly account of the first dog to orbit the Earth. Instead, it’s an entertaining but also educational overview of the life of an unwitting space pioneer. |

Laika is a blend of fact of faction, something readily acknowledged by the author and publisher. Since nothing is known (or could be known) about Laika’s life prior to its capture and delivery to Russian biomedical researchers, that portion of the book is a dramatization, culminating with its capture by a dogcatcher with an Ahab-like obsession regarding the dog. While later sections of the book also include dramatized passages, it’s based more solidly on actual history, and includes people like Sergei Korolev and Oleg Gazenko, a doctor involved with the effort who later regretted the decision to fly Laika: “We did not learn enough from the mission to justify the death of the dog,” he said over 40 years later, in a postscript included in the book. The author, Nick Abadzis, has clearly done his research, traveling to Moscow to learn more about Laika. He even goes so far to mention in a brief author’s note at the end of the book that he took pains to make the phases of the Moon rendered in various parts of the book astronomically accurate for the given date, although “I may have erred on the side of drama about the times of the moonrises.”

Historical purists may turn up their noses at Laika: real histories, they may argue, are texts with the occasional picture, not oversized comic books with dramatized characters and passages. However, Laika is not meant as a substitute for a proper scholarly account of the first dog to orbit the Earth. Instead, it’s an entertaining but also educational overview of the life of an unwitting space pioneer. Kept in that perspective, Laika is a fine way to introduce some space history to audiences who might never think to read a more conventional book on the subject.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site and the Space Politics and Personal Spaceflight weblogs. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone, and do not represent the official positions of any organization or company, including the Futron Corporation, the author’s employer.

|

|