Heinlein in Hollywoodby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Television and film naturally reach much broader audiences because they are primarily passive forms of entertainment, not requiring a person to do anything more than watch and listen. As author William Gibson has observed, novels require substantial cultural training of the reader in order to be accessible. Television does not. |

What follows is a partial summary of two of these latter panels. The only panel not covered is the one on Heinlein and animation, a genre that is admittedly thin, but also contains one of the more notable adaptations of a Heinlein novel. During the late 1990s Sony Pictures produced Roughnecks: The Starship Troopers Chronicles, a lengthy animated television show based on Heinlein’s 1959 book Starship Troopers. Unlike the much better-known 1997 movie, Roughnecks was far more consistent with Heinlein’s original work, both narratively and thematically. The computer-generated animation was bold considering the year and the venue, but still relatively crude, and the series ended without a proper conclusion. But the series was relatively sophisticated for a show aimed primarily at children, and featured complex moral dilemmas as well as the deaths of several main characters. Heinlein probably would have been pleased with the result.

Heinlein on the idiot box

The panel on Heinlein and television was called “Heinlein on the Idiot Box” and featured television and fiction writer Michael Cassutt, Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America president and author Robin Wayne Bailey, television writer and author David Gerrold, and Heinlein biographer Bill Patterson. Patterson’s biography of Heinlein is due to be published in 2008 by Tor Books, and his knowledge of Heinlein’s life and works borders on being encyclopedic. The four panelists discussed the history of Heinlein’s projects that were adapted, or were considered, for television, and also the nature of the television industry, which they believe prevented more of Heinlein’s work from reaching the little screen.

The most important development in these early years was Heinlein’s book Space Cadet, a fun, sophisticated example of what are commonly referred to as Heinlein’s “juveniles,” books written for young boys. The book led to the much less impressive 1950 serialized television show Tom Corbett: Space Cadet.

In 1952 Heinlein was asked to put together several half-hour weekly shows for a proposed program called The World Beyond. The initial concept of the show was that each episode would start with a classroom in the future and a teacher would begin to tell a story from history—a history that had not yet happened from our perspective. The scene would then dissolve into that story.

Thirteen scripts were produced based upon published Heinlein stories with two of them originals written by Heinlein specifically for television. Jack Seamans was the producer. Unfortunately, the project was rushed and canceled before it ever made it to television. Heinlein wrote the pilot script called Ring Around the Moon, about the first mission to land on the Moon. Production started on the pilot, but at some point early in the filming two things happened: the television series was canceled and the pilot episode was converted into a movie that was renamed Project Moonbase (see “Sex and Rockets,” The Space Review, July 9, 2007). The movie’s star Donna Martel remembered that she never received a completed script, but was handed more pages in the middle of filming and informed that the television show had been turned into a movie. Heinlein’s wife Ginny wrote in the book Grumbles from the Grave that Heinlein was surprised when the television script was turned into a movie, but Patterson noted that Heinlein signed a contract to write a movie script and therefore must have known of the change and agreed to it.

| According to the panelists, one of the perennial problems with turning Heinlein’s existing works into television shows is that studios don’t want to do anthologies, they want to use recognizable regular characters in serial episodes—Star Trek rather than The Twilight Zone. |

The panelists said that throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s a number of Heinlein’s books and short stories were optioned for television, meaning that somebody bought the rights to the story in order to try and create a television show from it. This was essentially free money for Heinlein, because he received payment for a work that had already been published. But it also meant that he lost control of how his story was portrayed on television. However, none of these ever made it to production. One example was a planned series called Crater Base One. Heinlein wrote an original script and borrowed a title from a 1948 story, Nothing Ever Happens on the Moon, for an episode. But the project fell apart and never got filmed.

Not all of Heinlein’s encounters with television were so passive. In 1963 Heinlein was invited to create a 90-minute drama called Century XXII. He wrote a script called The Man Who Wasn’t There about a secret agent. According to Patterson the script was too daring for television and was not produced, and Patterson believed it never could have made it to the screen. According to Cassutt, after Century XXII fell apart in 1964, Heinlein’s interest and involvement in television waned.

According to the panelists, one of the perennial problems with turning Heinlein’s existing works into television shows is that studios don’t want to do anthologies, they want to use recognizable regular characters in serial episodes—Star Trek rather than The Twilight Zone. Patterson also noted that by the latter 1950s Heinlein’s books were selling so well that he did not really need the extra income of selling scripts to Hollywood. Although he never opposed optioning his stories, he never made much effort to break into Hollywood—he was already rich and had total control over his published work. However, according to Cassutt, there was another problem: the original television deal that resulted in Project Moonbase meant that many Heinlein stories were unavailable for decades because the option to produce them was owned by Jack Seamans—who never did anything with them.

Heinlein in the cinema

The session on Heinlein featured Michael Cassutt, short film producer Jeff Larsen, and Harry Kloor, who wrote several stories for Star Trek: Voyager and claims to be producing an adaptation of Heinlein’s story Have Spacesuit Will Travel.

Any discussion of Heinlein and the big screen must start with the 1950 movie Destination Moon (see “Heinlein’s Ghost,” The Space Review, April 9, 2007). The panelists noted that Destination Moon remains one of the few cinematic attempts to portray space travel as it really is. Heinlein insisted upon scientific accuracy and his enthusiasm apparently rubbed off on the cast and crew, ultimately resulting in a film that was as close to an accurate depiction of space travel as scientists and engineers could envision it, eight years before Sputnik.

Although Destination Moon was successful and influential on other movies that followed, and Heinlein followed it with the much less interesting and ambitious Project Moonbase, he never again wrote a script for a Hollywood movie. Heinlein’s notes and writings indicate that he was not pleased with the amount of creative control that he had to sacrifice while working on Destination Moon, but equally important, by the 1950s his books and stories were selling so well that he did not need Hollywood money, no matter how lucrative.

Mike Cassutt said that when Heinlein’s book Stranger in a Strange Land appeared in 1960 it was not initially very successful. But as its sales grew and it proved wildly popular by the early 1960s, various people in Hollywood sought to turn the countercultural manifesto into a movie. None of these efforts succeeded, however. Eventually American society changed, Cassutt noted, making such a project impossible. “The window for the Stranger movie closed around 1970,” he said, and there is no way that one of Heinlein’s most famous works could make it to the screen today.

| Producers and executives like stories that they are emotionally and mentally comfortable with. Science fiction inherently makes them slightly uncomfortable, and space makes them even more uneasy. |

Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s various people tried to turn Heinlein’s short stories into movies, but none of them progressed until the 1994 movie The Puppet Masters. The movie was eagerly anticipated by many Heinlein fans who were ultimately disappointed by it. The panelists discussed why the film seemed to lack energy and excitement, and generally agreed that the movie lacked big screen ambitions and felt more like a television show than a motion picture. They noted that the space aspects of the story—part of the action in the book takes place on Saturn’s moon Titan—were deleted from the film, something that Mike Cassutt doubted was simply due to time and budget and probably had more to do with Hollywood’s conservatism when it comes to science fiction.

Whereas film producers, unlike television executives, are looking for one-off stories rather than repeating characters (i.e. the anthology problem), film producers still share certain inherent biases about science fiction. Cassutt noted that both television and film executives are uncomfortable with science fiction that involves spaceflight and alien locales. They prefer that science fiction stories take place on Earth, in recognizable surroundings with recognizable people. There are various reasons for this, including production costs; it is more expensive to try and film a realistic-looking space scene, even on a soundstage, than it is to simply film in the forest outside of Vancouver. But equally important to production costs is what Cassutt referred to as the executives’ comfort level—they like stories that they are emotionally and mentally comfortable with. Science fiction inherently makes them slightly uncomfortable, and space makes them even more uneasy.

Cassutt said that this attitude is not confined only to studio executives. Actors also find it harder to act in science fiction shows, particularly those involving the far future and spaceflight, than more conventional dramas. “Every actor knows what a cop does and how he is supposed to act,” Cassutt said, “but they don’t know what a starship engineer does or how he acts.” The actors don’t know how to move, how to talk, or what to do on the elaborate sets. Put them at a console filled with buttons and, unlike driving a car, they’re not sure what they should do with their hands.

Bug attack

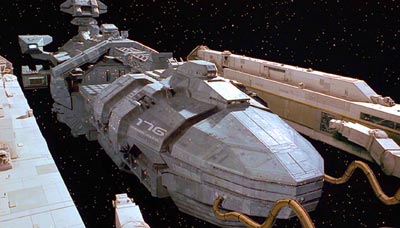

Of course, any discussion of Heinlein and the movies must inevitably address the 1997 Paul Verhoeven movie Starship Troopers, based on a book Heinlein wrote nearly four decades earlier. Starship Troopers often results in passionate arguments among science fiction fans, Heinlein fans, and film critics. Americans and Europeans frequently seem to view the movie from entirely different viewpoints. Entertainment Weekly ranked the movie as one of the 25 best science fiction films of the past 25 years, but admitted that this choice would undoubtedly draw fire from irate fans (the magazine told the fans to stuff it). In fact, the Heinlein Centennial symposium even featured an evening discussion of the film, with attendees encouraged to argue its merits late into the night.

Arguments over the film usually split along two lines: critics who believe that the movie is shallow, dumb and bluntly mocks Heinlein’s message, and fans who consider it to be a brilliant parody of militarism—indeed, a mockery of American values. Not surprisingly, Europeans tend to hold the latter view, believing that unsophisticated Americans fail to grasp how much the movie actually ridicules them. Of course, you don’t have to be a Heinlein fan, or an American militarist, to come to the conclusion that the movie is simply not very good, but usually the arguments are drawn along more ideological lines. Verhoeven has stated that over-the-top parody was his intention, but has also demonstrated a very thin skin about any criticism of his film.

Surprisingly, the panelists all agreed that Starship Troopers was not a bad science fiction film. “It’s not Heinlein,” Cassutt added, but it was a competently done grade B science fiction movie. None of the panelists felt that it was the brilliant parody that Verhoeven brags about, but neither did they consider the film as bad as many Heinlein fans claim. The panelists said that in order to appreciate the movie on its own level it was necessary to move beyond the fact that the story does not feature some of the innovations that made the book so unique, like the jumpsuits and the nuclear hand grenades, and ignore the fact that the futuristic infantry is portrayed as idiotic cannon fodder, rather than Heinlein’s more sympathetic and idealized elite soldiers.

The panelists also noted that Verhoeven—and not the limitations of the original Heinlein book—was the reason that the movie turned out the way that it did. The Dutch-born director was never a Heinlein fan and in fact was quite the opposite. He saw the movie as an opportunity to make a scathing social commentary about militarism and the United States, and so he deliberately molded the story to suit his ideological viewpoint. The original classic book was merely a vehicle for Verhoeven’s own political views, not a paean to Heinlein.

The panelists also all agreed that the direct-to-video Starship Troopers sequel was awful, and mentioned that a third movie was then being shot in South Africa. But none of them expected it to be anything other than junk.

| Surprisingly, the panelists all agreed that Starship Troopers was not a bad science fiction film. “It’s not Heinlein,” Cassutt added, but it was a competently done grade B science fiction movie. |

Larsen discussed the difficulties of bringing any literary work to film. Short stories are often better suited for this, because they provide an initial idea that can possibly be expanded to a feature-length movie. But often they can be too thin and lack the scope required of the silver screen. Alternatively, novels can be too long and detailed. The problem becomes what to throw away and still maintain the essential core of the book. Cassutt said that the ideal length of a literary work for adaptation to the screen is a novella. The page count of a novella and a movie script are just about equal, he said. He added that he has seen few books that have been translated to the screen and still stayed true to the original author’s intent. He thinks that Gone With the Wind, Slaughterhouse-Five, and The Last Picture Show are several examples of movies that captured the essence of the original works quite well.

Kloor briefly discussed his effort to adapt Have Spacesuit Will Travel to the screen, including his intention to delete the entire final courtroom drama. He said that his initial goal was to turn the story into a graphic novel, which he could then show to potential financiers and say “See? It will look like this.” But he acknowledged that there have been several previous attempts to turn this story into a film and all have failed.

Another classic Heinlein novel, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, has also been optioned several times, including quite recently. Unfortunately, it has never gotten beyond the initial script stage. A little over a year ago Tim Minear, who co-produced Buffy the Vampire Slayer and the much-heralded (and dearly lamented) series Firefly wrote a script for a Harsh Mistress movie. During a talk at a Firefly convention in December 2006 Minear said that writing the script for this Heinlein novel fulfilled one of his lifelong dreams, as he considers himself to be a libertarian and Heinlein was a big influence. Minear even gave away a copy of his script at the time and strongly hinted that he hoped somebody would leak the script to the Internet—something which has not yet happened.

With the Minear project dead, there seem to be few options for Heinlein fans to see their favorite stories make it to either television or the movies. For now they will have to be content to simply read the books.