The problem with Freedomby Dwayne A. Day

|

|

The series, echoing Akira, follows the exploits of a group of teenagers, led by Takera, who are raised communally and at age 15 granted their “freedom,” a six-month period before they are assigned their vocation for life. Eden’s society is run by the Citizens Administration Council, the blandly-named government that maintains peace, prosperity, and order in return for… what is not exactly clear.

| The series demonstrates that whereas a message can translate across language and national boundaries, the medium may not. |

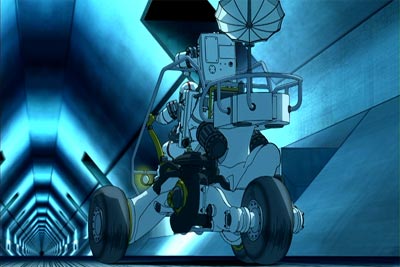

So far two episodes have been released in the United States. The first is somewhat thin on plot, primarily setting the stage by introducing the characters and their interests and providing limited glimpses of the world that they live in. Takera, like all teenagers, argues with his friends, is jealous of his rival, and develops a crush on a girl. His primary interest is fixing and racing his vehicle—essentially a three-wheeled motorcycle—that he races inside the domes and through the tunnels underneath the colony. Eden is massive and the sky underneath the domes is altered to look like Earth’s sky. When the boys get in trouble for their racing they are sentenced to community service, or “volunteer work” as the Citizens Administration Council calls it. It is while performing this boring duty—walking along a pipeline on the lunar surface to check for leaks—that Takera makes an intriguing discovery.

|

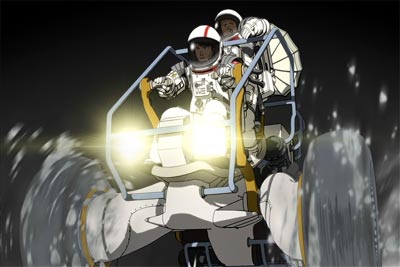

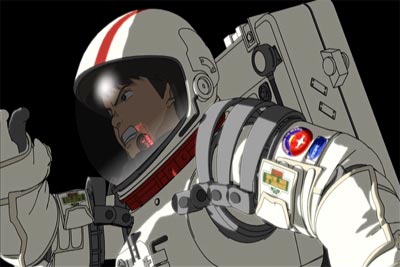

Although the first episode lacks much plot, it is visually interesting, and Otomo’s style is readily apparent. Otomo shares the same eye for technology as graphic designer Syd Mead, who designed the technological look of Blade Runner and who can draw a future that looks simultaneously real and lived in, and yet mystifying. We are no better at understanding many of the machines of Otomo’s or Mead’s worlds than someone from the nineteenth century could understand a microwave oven. Otomo clearly based much of the look for Freedom on the Apollo program and American space technology. Spacesuits, moonbuggies, and other equipment look like advanced versions of existing technology. In fact, two characters wear Apollo flight jackets even though they know very little about the ancient history of the first men to walk on the Moon. Other ideas, such as an abandoned mass driver for firing materials from the Moon’s surface, owe their origins to the work and ideas of NASA and American futurists like Gerard O’Neill.

|

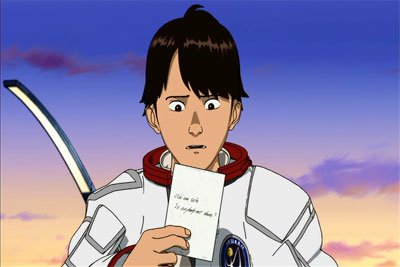

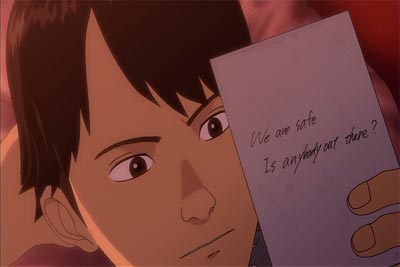

Unfortunately, the first episode drags, running the risk of losing the audience by taking nearly its entire 22-minute length to get to the engine that will drive the series forward. Too much talk and not enough plot. Fortunately, the story takes an important twist just at the point where it seems to be going nowhere. While on his boring pipeline inspection job, Takera witnesses a meteorite slamming into the Moon’s surface nearby. He goes to inspect the small crater and discovers the wreckage of a satellite. In the middle of the wreckage is a photograph of a smiling woman standing over a bunch of children on what looks like Earth. Written on the back of the photograph are the words: “We are safe. Is anybody out there?”

|

The Moon is a harsh mistress

In the second episode, Takera returns to Eden with the photograph and becomes obsessed with it. His friends dismiss his interest and say that he merely has a crush on the woman. That may be true, but clearly the photograph and its cryptic message represent a deeper mystery. Takera sets out to find the young woman in the only way he knows how—by walking around Eden and asking some of its three million inhabitants if they have ever seen her. Naturally this is pointless, but soon the boys notice that a structure in the background of the photograph looks familiar. It looks like a rocket launch pad on Earth that they’ve seen in a photograph owned by an old man named Alan that they’ve befriended. Alan is a bit of a curmudgeon and a drunk, but he is the only adult the boys trust and he offers to help them.

|

Takera begins asking questions about Earth. Could the girl really be from there? It’s not possible, his friends tell him; Earth has been destroyed, nobody lives there. How do they know, he asks? After all, they cannot see Earth from Eden because it is perpetually over the horizon. The boys do a computer search about Earth’s fate and suddenly they have unknowingly attracted the attention of the government, which begins monitoring them with cameras.

When the boys seek to go out onto the lunar surface to look at Earth, a computerized voice denies them exit. Fortunately, Alan, who is the supervisor for a long-abandoned part of Eden, has his own resources and loans them spacesuits and a lunar buggy. Takera and his closest friend rush out to the surface and head for the horizon, hoping to get far enough to see Earth before they have to turn back. They manage to travel far enough to not only see Earth, but to also confirm their growing suspicions. Earth is not the brownish destroyed globe that they have been told it was, but hangs blue and beautiful in the sky. Equally stunning, they find more evidence that there are people alive on Earth who have been sending messages to the lunar surface. Unfortunately, Takera and his friend discover this just as the authorities arrive to arrest them both, and they flee in their moon buggy.

|

Visions of heaven

Ever since the end of World War 2, Japan and America have had substantial influence on each other politically, economically, and culturally. The Japanese love certain aspects of American pop culture, including Mickey Mouse, Elvis, and bobbysoxers, to name a few of the more clichéd examples. Japanese pop culture has had significant recent influence on the United States. The Hidden Fortress formed the basis for Star Wars three decades ago, but more recently Japan has shown up in The Matrix, numerous horror movies, and Quentin Tarantino’s twisted id. Freedom reached the United States riding on a wave of popularity for Japanese anime and manga (i.e. comic books), something that is evident whenever you wander into Borders or Barnes & Noble, or turn on cable television.

| How does one define freedom beyond the limits of happiness, safety, and satisfaction of basic requirements like food and shelter? What does “freedom” mean if reality is a lie? |

Freedom is similar to another recent Japanese animated series about near-future space exploration, Planetes. (See “Hardhats, salarymen, and zero-g: A Japanese vision of humanity’s future in space”, The Space Review, September 5, 2006) It exists along with a few other Japanese animated anime—most notably the classic Cowboy Bebop—that seek to portray a realistic possible future in space. (see “A new life awaits you in the off-world colonies (enjoy the crime… and the jazz)”, The Space Review, March 26, 2007) There are no giant robots, magical powers, demon overlords, or faster-than-light travel in space battleships, just people who happen to work and live in space. But these titles represent the exception rather than the rule when it comes to Japanese animated science fiction, where fantasy still reigns supreme.

|

Although with only two episodes released in the US so far it is difficult to tell, but Takera appears to be a classic anti-hero who does not seek to overturn corruption and deceit, but does so out of personal interest and a growing awareness of the reality around him. The story in the first two episodes has so far only hinted at some larger themes, most notably the classic question of whether security and stability are more important than freedom and liberty. How does one define freedom beyond the limits of happiness, safety, and satisfaction of basic requirements like food and shelter? If the entire society is being lied to about the situation on Earth does that really matter? What does “freedom” mean if reality is a lie?

Such philosophical ideas can transcend cultures. Unfortunately, certain aspects of the Japanese business culture have not transitioned well, and they represent the biggest problem with the series.

Failing to sell the Moon

The problem with Freedom is not the story or animation or characters, but the presentation and distribution. The fact that episode one (“Freedom 1”) was released in the United States in June, episode two (“Freedom 2”) was released in September, and as yet there appears to be no release date for episode three demonstrates exactly what is wrong with this series. Who wants to purchase and view such short episodes over an extended period of time? Why would anybody wait?

A little bit of background is in order. In Japan, manga is everywhere, and thousands of different titles are published every year, aimed at everybody from children to businessmen to housewives. There are manga for male students, manga for female students, manga for men in the insurance business, manga for Christians, manga for masochists, manga for perverts. A recent development has been manga for cell phones, enabling men to read illicit titles while crammed into a Tokyo subway. Japan’s anime market is not as big, but still quite diverse, catering to every taste, and operating by different economic rules than in the United States.

|

One staple of the anime genre is the direct-to-video title (which goes under the moniker Original Video Animation, or OVA, as loosely translated from the Japanese). In the United States, direct-to-video has so far had a negative connotation, implying cheaply produced junk (although that market, like all multimedia markets, is fracturing and mutating: witness several television shows now being revived on DVD long after their cancellation). But in Japan, direct-to-video often has a positive reputation. Customers eagerly await each new title and pay a premium for it. Thus direct-to-video productions like Freedom can have large budgets and relatively high quality, often better than televised anime. In addition to Katsuhiro Otomo’s name on the project, one of the primary selling points for Freedom in Japan was that it was being released as the first anime series filmed in HD-DVD.

Freedom shared another common Japanese characteristic—corporate sponsorship. The show was sponsored by a noodle company, which paid for substantial print and television ads depicting the characters eating the company’s product. The Tokyo subway was plastered with Freedom ads for months before its appearance at video stores. That is not unusual for Americans who this past summer were bombarded with Chevy television commercials tied into the Transformers movie.

But whereas the Japanese can be shrewd businessmen capable of taking the American market by storm (witness the Nintendo Wii or the Toyota Prius) sometimes they can demonstrate complete ignorance of what Americans want. This is clearly the case of the Freedom distribution approach which is more like the release of Harry Potter books than a television DVD. In Japan, four episodes have been released so far, the first in November last year. The fifth is scheduled for release late this month. Each release was accompanied by a print and television advertising campaign tied in with commercials for the corporate sponsor. That’s six 22-minute episodes released over slightly more than a year.

| But whereas the Japanese can be shrewd businessmen capable of taking the American market by storm (witness the Nintendo Wii or the Toyota Prius) sometimes they can demonstrate complete ignorance of what Americans want. |

But for some reason, Bandai has decided to emulate the Japanese release schedule in the United States, which lacks Japan’s fascination with anime and Otomo’s name recognition, and without any accompanying advertising campaign. Who other than a few die-hard anime fanatics is going to await each new release, especially when they are spread so far apart? More to the point, who is going to be willing to pay $28 per episode ($40 if you pay full price) for six episodes, or about $180 for approximately two hours of entertainment delivered over eight months? It’s a ridiculous distribution schedule and price for the much smaller American anime audience. Although renting the episodes is far cheaper, it still does not make them arrive faster, since four episodes remain unavailable. In the United States, television shows like Heroes and The Office frequently put out an entire season of episodes within a few months after the season ends, and even die-hard American anime fans are not going to accept Freedom’s ridiculous distribution schedule.

|

As if to punctuate this contempt for the audience, Bandai has gone a further step when it comes to the DVD formatting and extras. Neither episode is dubbed into English, forcing the viewer to read subtitles throughout. Anime fans often insist that this is the only way to watch the shows and not lose the original language. But film is a visual and audio medium, and if you have to read the dialogue on the bottom of the screen you will miss much of what is happening. Even in non-HD-DVD format Freedom has beautiful animation, mixing both 3D and 2D elements with smooth movement and excellent detail and color, but much of the effect gets lost when you’re using your eyes to read what you should be able to hear. Furthermore, the disk extras can only be accessed through an HD-DVD player with an Internet connection, equipment that is still rare in the United States. Even so, the extras apparently only consist of commercials for the DVD, and the noodles. More interesting subjects, such as interviews with the animators and Otomo, have apparently not even been offered in Japan.

The slow release schedule, the lack of English dubbing, and the absence of any extras are part of a bizarre approach guaranteed to alienate American fans. At some point the studio will release a collected set, hopefully with extra features, and it may be worth purchasing then—or maybe not. Japanese anime distributors seem to have unwittingly adopted the goal of confusing their fans in the United States, frequently releasing, and then re-releasing titles without clearly identifying differences between them, sometimes changing nothing but the box and title. They compound the problem with confusing names that don’t have any cultural resonance in the U.S., like “The Purple Sunflower Collection.” Only an anime junkie with pink hair could make any sense of this. For the rest of us who have only occasional interactions with this world, it all seems so… foreign.

That is the biggest problem with Freedom—we shouldn’t have to wait for it. Right now, the story and characters and animation seem to promise an interesting vision of humanity’s future in space, and possibly a deeper philosophical exploration of what citizens should expect from their government, but we don’t want to wait too long for this plot to play out.