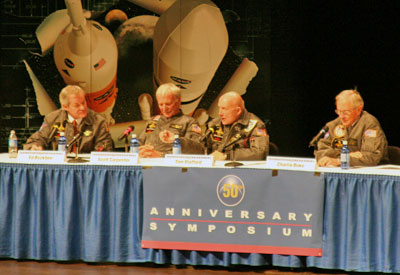

Recall and remembrance in Rocket City<< page 1: remembering Explorer 1 The Omega Space CowboysThe second panel of the day, called “Conversations with the ‘Real Space Cowboys,’” was chaired by former NASA public affairs officer and former head of the US Space and Rocket Center Ed Buckbee. Buckbee is co-author with the late Wally Schirra of The Real Space Cowboys (see: “Review: The Real Space Cowboys,” The Space Review, July 25, 2005). Buckbee was joined by Mercury astronaut Scott Carpenter, Gemini and Apollo astronaut Tom Stafford, and Apollo astronaut Charlie Duke. With Buckbee leading the conversation, the three astronauts spoke about their experiences, accompanied by an excellent slide and video presentation. Carpenter spoke about his post-Mercury experiences, including underwater research, and credited two men with getting America to the Moon: John F. Kennedy and Wernher von Braun. Stafford discussed his experience on Apollo 10 “drawing a line to the Moon” for the first lunar landing mission, but spent much of his time discussing the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz mission. He confessed that learning Russian for the flight was probably the most challenging thing he did during his entire astronaut career. From a space history perspective, Stafford’s most important and interesting contributions to the American space program occurred after he left the astronaut corps, and he has served as an important advisor for a number of key space projects. But he did not talk about any of that while on stage, and in all fairness, a general public audience probably would not have been interested.

Apollo 16 lunar module pilot Charlie Duke had the most interesting and amusing talk, showing images of himself walking and stumbling on the Moon, as well as riding in the lunar roving vehicle that they brought along to the surface. He described how when he sat down in the vehicle in his spacesuit he had to use the seat belt to actually bend his waist so that he was sitting in the chair. The seat belt was necessary because the vehicle offered a bumpy ride. He praised the vehicle’s handling qualities and noted that the designers—who worked in Huntsville—had made a number of clever choices, including the rover’s wire mesh tires which handled both dust and rocks with ease. He said that the rover proved remarkably maneuverable. Although it could be backed up, the two astronauts never used that capability, choosing either to make U-turns or to physically pick up the vehicle and turn it around. Duke did not get to drive the rover, but figured that he had the better deal because this allowed him more opportunity to look at the terrain than commander John Young. Buckbee asked some excellent questions, some of them provided by the audience, and the entire presentation had clearly been polished over numerous appearances. At one point Buckbee asked about being scared and how they dealt with it. Duke admitted to being truly scared at one point during a spacewalk when he fell backward, realizing that his backpack and life support equipment would take a blow for which it had not been designed. He managed to recover, however, but believed that he had suffered a close brush with serious danger. Surprisingly, none of the men responded that the military had trained them so well that in times of great danger their training took over and helped them to cope with any fear. The audience clearly enjoyed the stories of the astronauts and their antics far more than the historians’ panel, and at any event like this the astronauts are treated as heroes who put their asses on the line in the effort to beat the Soviets. However, as frequently happens whenever a group of astronauts take the stage, the stories tended to focus primarily on funny anecdotes and pranks and the “human interest” angle rather than what the astronauts were really supposed to accomplish during their missions. For instance, Duke and Apollo 16 commander John Young each conducted over 20 hours of extra vehicular activities on the lunar surface during one of the most scientifically important Apollo missions, but Duke said almost nothing about what he and Young did other than drive the rover, fall down, and pick up some rocks. Based upon Stafford and Duke’s talks, one would get the impression that the United States spent $23 billion in the 1960s so that a handful of astronauts could have a lot of fun in space. On the other hand, at a time when increasing numbers of Americans, particularly young people, believe that the Moon landings were faked by a duplicitous American government, it is probably extremely valuable for them to be exposed to stories like Stafford’s and Duke’s. In order to believe the Moon hoax claims, people watching and listening to Duke would have to believe that he was lying about nearly everything he said, including such mundane details as how the astronauts adjusted the footrests in the lunar rover, and used a vacuum to clean lunar dust off themselves once they returned to the spacecraft. What kind of conspiracy theory planning committee could invent that many details? What kind of person could invent them on the fly? The reason that the discussion was so professional and polished is that “The Real Space Cowboys” is actually a roadshow. Buckbee and the astronauts have made numerous appearances around the country sponsored by the Swiss Omega watch company. Omega is celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of its Speedmaster watch, which was used by the astronauts. Omega saw an opportunity to tie its fiftieth anniversary with the anniversary of Sputnik, Explorer 1, and undoubtedly NASA, and ran with it. Thus, Omega’s logo was frequently shown throughout the astronauts’ talks and the company was listed as an event sponsor. Sometimes the astronauts themselves put in direct plugs, and it was hard to keep from laughing when Charlie Duke made comments like “Here’s a picture of me on the surface of the Moon. You can see on my left arm one of the checklists that we used listing our timeline and the things we had to accomplish. And on my right arm is my Omega Speedmaster watch…” Admittedly, they’re nice watches (and if Omega wants further plugs in The Space Review, all they have to do is send me a brand new Professional Speedmaster Moonwatch “From the Moon to Mars”). Omega clearly provided substantial funding to make the various events possible, but the clash between capitalism and spaceflight seemed a little too blatant at times. A vision without funding is a hallucinationThe third and final panel was called “The Next Fifty Years in Space – Visions of the Future.” The panel was chaired by Steve Cook of NASA’s Ares Projects Office. Panelists included space journalist Leonard David, author and Huntsville resident Homer Hickam, and Tim Pickens, the CEO of Orion Propulsion. Leonard David recalled how when he was a boy growing up in San Diego his neighborhood was filled with engineers and technicians working on the Atlas missile and Centaur upper stage. David befriended his postman, who regularly gave him stacks of undeliverable, non-forwardable technical magazines. So he got piles of Aviation Week, Missiles and Rockets, Astronautics and Aeronautics, and many other technical publications. One day he got a directory of the membership of the American Institute of Astronautics and Aeronautics. “Eureka! A gold mine!” David remembered. Inside were the addresses of all the space engineers he was reading about in the technical journals, “even their home addresses!” So he used his Royal typewriter to make himself “a royal pain in the neck” and began typing letters to all of these people, asking them to send him everything on their desk. He broke the “R” on his typewriter writing “rocket” so much. Soon his collection of missile and rocket publications got even bigger. As a teenager he started a classified project. He built “an experimental prolonged isolation chamber” out of wood to test what it would be like to spend a long time in a spacecraft. His mother called it a coffin. He used a vacuum cleaner set on reverse to pump air into it. He even had a waste management system—a jar. He sent the results to NASA: a box at night gets cold. Many years later David found himself working on the National Commission on Space, seeking to outline what the United States should do next in space now that it had the Space Shuttle up and running. They were finishing up the report when the Space Shuttle Challenger came apart in a cold blue Florida sky. Soon the White House was calling, asking them to quickly finish the report; “give the people a vision of the future” to explain “why the Challenger 7 lost their lives.” But in the days and weeks following the accident the political atmosphere quickly soured. People were more interested in finger pointing and finding blame, and soon the White House told them to hold off on the report. David said that the National Commission on Space gave him a vision of the future, but also a hard lesson in reality.

As to the question of where America is headed in space “I haven’t a clue,” David confessed. But he did offer a few thoughts. One was that humans needed to take better care of our launch pad, Planet Earth. He also noted that people were already starting to play the space “race card” in Washington, claiming that the Chinese would beat the Americans (back) to the Moon. He also suggested keeping an eye on Burt Rutan whose SpaceShipTwo will soon take to the air. But he ended with a song that his parents were fond of, “Que sera sera,” and its lyrics that “the future’s not ours to see.” Leonard David was followed by Homer Hickam, who wrote the 1998 book Rocket Boys, which was made into the 1999 movie October Sky (a clever anagram for the original book title). Hickam told a number of somewhat rambling anecdotes about growing up in a West Virginia coal mining town. Hickam was inspired by Sputnik to start building his own rockets, fortunately failing to blow himself up throughout high school. Hickam recalled how Senator John F. Kennedy swung through the area on a campaign trip and gave a rather disastrous speech where he talked about coal mining as a dying industry to coal miners who wanted to hear none of it. Hickam was in the audience that day. Whereas the coal miners were grime covered and wearing their work clothes, the teenaged Hickam was wearing what he said was a ridiculously orange suit that he had just purchased, and which made Kennedy notice him when the young man raised his hand. Hickam asked Kennedy about the space program, only to receive a blank response from the senator, who finally turned the question back around and asked Hickam what he thought about it. Hickam’s response was that America should fly to the Moon—and mine it. Hickam joked that he was personally taking credit for giving Kennedy the idea of the Apollo program. Hickam served in Vietnam during the Apollo program and it was not until the 1970s that he finally became a rocket engineer, working on the Space Shuttle program. He retired from that life long ago to write books, but most of his writing these days is fiction and has nothing to do with the space program. He did not have much to say about the future of spaceflight other than that perhaps Americans should travel to the Moon, and mine it. Tim Pickens then spoke about his experiences as an entrepreneurial rocket developer. He got his start in amateur rocketry, he said, and then graduated to bigger projects, including working on Burt Rutan’s SpaceShipOne. Pickens said that although he was dedicated to building rockets cheaper and faster than NASA, he had seen many entrepreneurs turn big fortunes into little ones by being too ambitious. He had eventually learned—mostly by watching others fail—that building a complete rocket system was too much work for a single company or person. The key was to focus on individual components as part of a much bigger effort and do your best to build them as cheaply and efficiently as possible. The last presentation was by Steve Cook, who demonstrated an impressive bit of simulation software that depicted how NASA currently plans to return humans to the Moon. Behind the speakers was a large projection screen visible throughout the auditorium. Using a hand controller similar to that developed for the Nintendo Wii, Cook showed a three-dimensional computer image of the planned Ares 5 launch site at Cape Canaveral. Cook used the controller to manipulate the point of view and zoom in on the rocket, then start the launch sequence. The rocket rose up into the air and Cook moved the point of view around it in flight. He then shifted back to an exterior view and changed to an image of the Ares 1 rocket sitting on its pad awaiting launch. He launched the rocket and again rotated the image around, at one point clicking on the Orion spacecraft itself to show a view inside it. It was clearly a cutting-edge simulation tool, but whether it impressed anybody under 18 years old in the auditorium is unclear: teenagers take this kind of technology for granted these days, largely unaware that it barely existed merely a decade ago. The question and answer session following the panel featured some of the same tired and clichéd questions common to these kinds of events. There was a question about how to inspire young people to pursue science and engineering degrees, but none of the panelists seemed to have a novel answer. The Sputnik that drew Homer Hickam out of a West Virginia coal town was ancient and virtually incomprehensible history to the teenagers in the audience, and it is doubtful that they would have attended the symposium if they had not been forced to be there. The panelists were also quizzed about the current Vision for Space Exploration and what they foresaw as its future. Clearly the Vision and particularly the Ares 1 and Ares 5 launch vehicles are important for providing the Huntsville area jobs—something that everyone from the mayor to the Alabama lieutenant governor mentioned at various events surrounding the Explorer 1 anniversary. But nobody present seemed to provide a ringing endorsement for a return to the Moon, and some noted that the project had not received sufficient funding. Pickens had probably the best quote of the day, stating that “a vision without funding is a hallucination,” a comment that brought nervous laughter from the audience. CelebrationIn the evening after the symposium the nearby US Space and Rocket Center hosted what was probably one of the largest social events in recent Huntsville history, a gala dinner underneath the beautifully restored Saturn V rocket inside the newly completed Davidson Center for Space Exploration (see “Fire and Grace,” The Space Review, February 4, 2008). The gala event was a truly impressive production, with special lighting, plasma screen televisions along the 120+ meter length of the building, and a central stage equipped with lighting and television cameras to transmit the event to the assembled guests as well as via the internet to those who could not obtain tickets. While a rainstorm raged outside of the brand new building, 1,400 guests and dignitaries dined on Chilean Sea Bass, filet mignon, and wine at tables that featured a centerpiece of a Saturn V rocket rising on a lighted Lucite pillar. The special guests included Paul Calle, one of the original artists in NASA’s Fine Art Program who painted “Power to Go,” a stunning painting of a Saturn V liftoff. Also present were Homer Hickam and a gaggle of astronauts: Scott Carpenter, Walt Cunningham, Bill Anders, Rusty Schweikart, Buzz Aldrin, Richard Gordon, Jim Lovell, Charlie Duke, Owen Garriott, Tom Stafford, Jan Davis, Jim Halsell, Tom Jones, Doug Wheelock, and Dan Brandenstein. (I sat at the “Apollo 13” table and only later did I realize that I should have tried to locate Lovell and get him to sign my table placard.) Then there were all the local officials to officiate in an official capacity. These included the CEO of the US Space and Rocket Center, Brigadier General (ret.) Larry R. Capps; Marshall Space Flight Center Director, David King; and Major General James Myles, the Commanding General of US Army Aviation & Missile Command. Natalia Koroleva was once again honored for her father’s achievements. Naturally the gala was long on ceremony and speeches, with various speakers thanking lists of dozens, if not hundreds of people—as one would expect of an event with a major goal of mentioning virtually everyone who had donated money to the Saturn restoration and building construction. The event started with a rousing national anthem that nearly brought the house down, and then a religious invocation that was nondenominational and surprisingly stirring, with vivid imagery of God’s power, greatness, beauty and glory, somehow fitting for people sitting underneath a giant rocket.

Among all the fatuous praise and self-congratulation (at one point Tom Stafford even presented an Omega Speedmaster watch to the museum), and talk about just how important the missile and space programs have been to local business and real estate development (driving home the fact that NASA centers are all about jobs for their local communities) there were videos about Explorer 1’s launch and the construction of the new Davidson Center. The gala finally culminated in a “reveal” of the Saturn V rocket (that had been looming over everybody’s heads for hours) which was a marvel of special effects involving a light and smoke show simulating a rocket launch. As one who has over the years lost faith in God, human spaceflight, and country (pretty much in that order), for one brief shining moment I got all—well most—of it back. Then it went away again. It always does. But it was nice while it lasted. ConclusionHuntsville’s fiftieth anniversary celebration of the launch of Explorer 1 reflected the contradictory tensions of any anniversary. For some such an event is little more than an excuse for a giant feel-good party, full of fatuous speeches, hyperbole, and much drinking. Historians trying to use such an event to teach a temporarily captive audience must fight these tendencies toward superficiality, and they inevitably lose. The symposium event and the gala dinner that followed it at times seemed somewhat surreal. The honoring of von Braun is understandable, although at times a bit overblown and out of proportion to his actual achievements. The honoring of Sergei Korolev also seemed a bit… odd. To paraphrase Harlan Ellison, the only thing more common in the universe than hydrogen is irony, and there was plenty of irony to breathe in that day—here was a patriotic American celebration that included honoring two people who at one time had built weapons for enemies to aim at us. Huntsville has long sought to underplay von Braun’s work on the V-2 rocket, and certainly any involvement in the slave labor camp at Dora (and the gift shop in the US Space and Rocket Center does not feature Michael Neufeld’s highly-regarded von Braun biography). But the community has at times so praised von Braun and his German “Rocket Team” that they have overplayed von Braun and the Rocket Team’s importance, distorting a far more complex history of American technological achievement. Von Braun was certainly a pioneering rocket engineer and an excellent program manager. But there were valid reasons that his proposal lost the competition in 1955 to build and launch America’s first satellite. The Naval Research Laboratory was a world leader in the much less visible, but much more important area of microelectronics. By 1957, the Army was no longer at the cutting-edge of missile and space technology in the United States. And as Stephen Johnson has demonstrated, in the early years of the Apollo program, an influx of Air Force technological and management expertise was vital for putting Apollo on track to beat the Soviet Union to the Moon. There is a tendency toward historical reductionism whenever history is discussed in public forums—people naturally want to reduce history to a set of simple stories, thought-provoking or funny anecdotes, and key personalities. Honoring Sergei Korolev underneath a relic of the rocket that beat him to the Moon was more than the action of a magnanimous winner in the Cold War, it fit the narrative of reducing the Space Race to a competition between two key individuals, Korolev and von Braun. That narrative, however, is so vastly oversimplified that it is simply wrong. Wernher von Braun may have been the most visible person in getting America to the Moon, but he was certainly not the only important person in getting America to the Moon. Other key figures, including George Mueller, Rocco Petrone, Sam Phillips, Jim Webb, and large teams of engineers at North American Aviation and Grumman—not to mention Rocketdyne and even Chrysler—played vital roles as well. That’s a story that historians struggle to tell, and have only partially succeeded. As we head towards the next big fiftieth anniversary celebration, the creation of NASA, the historians’ struggle will continue. Home |

|