Messy battlefieldsby Taylor Dinerman

|

| When it happens, war in space is going to be a very messy business, especially in low Earth orbit (LEO), where most of the really lucrative targets are. |

Any weapon, defensive or otherwise, will produce unexpected effects. It was predictable that in World War 2 fragments from exploding anti-aircraft artillery shells would fall back to Earth. In spite of this, many Londoners were killed by shrapnel from the barrage that was supposed to protect them. Minefields are another example of this problem: who could imagine that, more than sixty years after the end of the Second World War, parts of Egypt and elsewhere would still be no-go areas thanks to these weapons? Looking further back in time, the kings of England during the Hundred Years War might never have deployed their longbow-armed peasant warriors if they had realized how devastating these weapons would be to the feudal and monarchial order.

When it happens, war in space is going to be a very messy business, especially in low Earth orbit (LEO), where most of the really lucrative targets are. Big high-performance spy satellites are especially important. They provide those nations that own and operate them with very high-resolution imagery across swaths of the electromagnetic spectrum. Knocking them out in the first moments of a conflict is going to be a priority.

During the Cold War this was expected and planned for. The US expected to USSR to knock out its big Keyhole satellites as a prelude to an all-out nuclear attack. It was one of the reasons why some leaders in the US figured they could count on at least a small margin of early warning. Today, when the possibility of a major nuclear war has receded, space warfare may be fought without the cloud of atomic uncertainty hanging over every operation.

According to one report in Aviation Week, the US is now building a pair of advanced Keyhole satellites at a cost of about $15 billion. The idea that the US will launch a defenseless military asset that costs $7.5 billion seems to defy logic, yet that is exactly what the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) seems to have in mind.

As space technology spreads, the incentives for small and medium-sized states to seek space warfare capability increases. A dictator who does not want to end the way Saddam Hussein did may seek way to hurt US warfighting capability in such a way as to impose major costs and casualties on the US early on. The destruction of a major US satellite would be both a substantive and a symbolic victory over the US. Hitting a number of satellites would increase the effect.

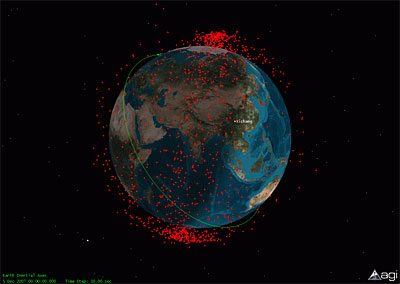

Such an attack would result in a major increase in the amount of debris orbiting the Earth. This would be the equivalent of a “scorched earth” policy if enough deadly debris were created. One possibility that has not been publicly examined might be to build highly- or ultra-destructive ASAT weapons that would literally pulverize the target and leave nothing behind but bits of dust. Even small particles can do some damage, but paint flakes like those that sometimes hit space shuttles have not managed to destroy an orbiter.

Of course, the orbiters were not designed to survive any serious collision, but why should future military spacecraft be designed to what are essentially civilian specifications? Since it is obvious that preparations must be made to survive combat in space, why not build spacecraft that are harder to shoot down than the ones currently deployed or planned? Why make life easy for the enemy?

| Since it is obvious that preparations must be made to survive combat in space, why not build spacecraft that are harder to shoot down than the ones currently deployed or planned? Why make life easy for the enemy? |

For the moment the only answer the US has is to try and develop an early warning system that would move the targets out of the way. This would result in a loss of the satellites’ on orbit lifespan. If repeated often enough, such attacks would force the target satellite to use up all its fuel and become almost as useless as the crippled NRO satellite the US Navy shot down last month.

Protecting this type of large, expensive satellite will be no easy job, but then neither is protecting a large expensive surface warship. As with a warship, giving a spacecraft a multilayered defense that would include both “hard” and “soft” defense mechanisms is going to be the most effective answer. One thing is for sure: if the US continues to build and launch multi-billion-dollar defenseless targets, potential foes will take note.

One potential answer is to build clusters of small or medium satellites that can operate together. DARPA is now working on such a concept. The Air Force’s Operationally Responsive Space program is another potential answer. Unfortunately, it will be many years before these programs bear fruit and, even then, integrating the new system into an effective concept of operations will take even longer.

What is needed now is to begin a relentless search for ways to harden and protect the satellites that are already in development, to give them fuel supplies that will allow them to dodge a whole series of ASATs, and to prepare for the day when the politicians decide that launching tens of billions of dollars worth of defenseless military hardware into orbit may not be the most intelligent way to prepare for future conflicts.