British perspectives on human spaceflightby Jeff Foust

|

| “If I was an American, I would be opposed to a return to the Moon and going to Mars,” Lord Rees told the BBC. |

Those beliefs are hardly new for Lord Rees, who for years has argued against government human spaceflight programs. “The practical case for manned space flight was never strong, and it gets weaker with each advance in robotics and miniaturisation,” he wrote in his 2003 book Our Final Hour, which famously predicted that humanity had a 50 percent chance of going extinct by the end of the 21st century. “There may be long-term economic benefits from space, but these will be implemented by robotic fabricators, not by people.” At one point in the book he called the International Space Station a ““turkey’ in the sky” that “can do nothing to justify its price tag.”

However, in that book Lord Rees was supportive of private human spaceflight ventures, believing that they would evolve over time from simple pleasure jaunts in low Earth orbit into privately-funded expeditions to the Moon and beyond. Such efforts, he argued, would be more willing to accept the higher levels of risk associated with them than government missions ever could. “If high-tech billionaires like Bill Gates or Larry Ellison seek challenges that won’t make their later life seem like an anticlimax, they could sponsor the first lunar base or even an expedition to Mars,” he wrote.

Although Lord Rees is well known in the scientific community, particularly in astronomy, his fame pales in comparison to fellow Cambridge University professor Stephen Hawking. While Hawking is arguably the most famous scientist alive today, few people would be able to discuss exactly what Hawking studied or the discoveries he has made. Instead, he is best known for suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)—aka Lou Gerhig’s Disease—that has paralyzed his body but left his mind intact.

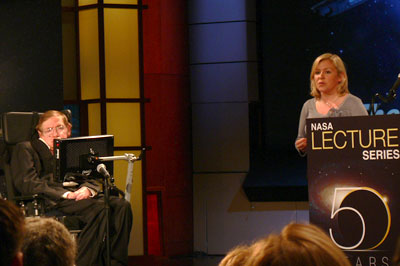

Hawking has also, in recent years, become a more vocal proponent of human spaceflight, government or commercial (he has expressed an interest in flying into space himself on a Virgin Galactic suborbital flight, and last year experienced weightlessness on a Zero-G airplane flight.) The importance of, and need for, humanity to venture into space was the subject of a speech he gave April 21 at George Washington University in honor of NASA’s 50th anniversary.

The speech, titled “Why We Should Go Into Space”, was billed as a brand new lecture that was being given for the first time that day, but it actually contained many elements and concepts that Hawking had previously discussed in books or lectures. The speech was something of a triptych: three parts, covering three different areas, all loosely organized around the theme of the importance of human spaceflight.

| Hawking: “Spreading out into space… will completely change the future of the human race and maybe determine whether we have any future at all.” |

The first part tackled the subject head-on, and addressed the opposition to human spaceflight by Lord Rees and others. “Robotic missions are much cheaper and may provide more scientific information, but they don’t catch the public’s imagination the same way, and they don’t spread the human race into space, which I am arguing should be our long-term strategy,” Hawking said. He advocated some goals that were a bit more ambitious than what NASA is currently pursuing. “A goal of a base on the Moon by 2020 and of a man landing on Mars by 2025 would reignite the space program and give it a sense of purpose in the same way that President Kennedy’s Moon target did in the 1960s.”

In the second part of the lecture, Harking turned the stage over to his daughter Lucy, an author, to discuss the importance of space exploration as a tool for enhancing education and scientific literacy. While many in America have wrung their hands over the low levels of interest in and knowledge of science, she noted it is also a problem in the UK: according to one survey, she claimed, a third of British students thought Winston Churchill was the first man to walk on the Moon. “Sorry about that, NASA and Neil Armstrong,” she said.

She argued that astronomy and space, including human spaceflight, can have a major influence on getting students interested in not just those subjects but science in general. “We are not saying that all children need to grow up and go into space, but we are saying that the work done by NASA has a profound and lasting impact on the way that children view their life on Earth, their cosmic environment,” she said.

Stephen Hawking spent the final third of the speech addressing the issue of life beyond Earth, comments that got the biggest play in the media immediately after his talk. Hawking said he believed that primitive life was “relatively common” in the universe, but that intelligent life, by contrast, was rare. He than advocated for human exploration of not just the solar system, but solar systems around other stars that might contain Earth-like planets. “We should make interstellar [flight] a long-term aim,” he said. “By long term, I mean over the next 200 to 500 years.”

Hawking was warmly received by the audience in Washington, treating him with a level of reverence like that shown for the Pope during his visit to the city a week earlier. When Hawking first appeared on the stage with an assistant who got him ready to deliver his remarks—a process that took a couple of minutes—there was nary a murmur in the auditorium. At the end of his remarks, he was greeted with an extended ovation that spontaneously became a standing ovation. Yet, the practical impact of his address was uncertain. At one point in his speech he argued for spending a quarter of a percent of world GDP on space exploration: “isn’t our future worth a quarter of a percent?” he asked. With world GDP in 2007 estimated to be $54.4 trillion by the International Monetary Fund, a quarter of a percent would work out to $136 billion, or about eight times the current budget for NASA, the space agency that far and away spends the most money. How to radically increase that amount was not something Hawking addressed.

Instead, he focused on the big picture. Human exploration of space, he argued, “won’t solve any of our immediate problems on planet Earth, but it will give us a new perspective on them and cause us to look outwards and inwards.” He added: “Spreading out into space… will completely change the future of the human race and maybe determine whether we have any future at all.”