The (not so) big switchby Jeff Foust

|

| The conventional wisdom coming out of the speech was that Obama had made a 180-degree shift in his space policy: the Orlando Sentinel called it a “dramatic reversal”. |

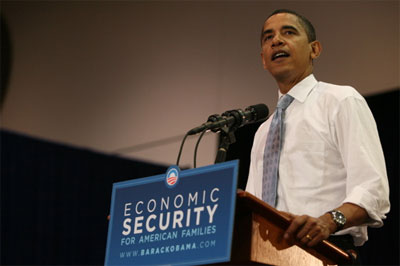

Sure enough, Obama did talk about space, and made some waves in the process. He devoted a few paragraphs of his speech to space policy, then, in response to a question, overturned a controversial statement his campaign made in November, where, tucked away at the end of a 15-page education white paper, he proposed to pay for part of his educational initiatives by delaying NASA’s Constellation program by five years. “I know it’s still being reported that we were talking about delaying some aspects of the Constellation program to pay for our early-education program,” the Orlando Sentinel quoted Obama as saying. “I told my staff we’re going to find an entirely different offset, because we’ve got to make sure that the money going into NASA for basic research and development continues to go there. That has been a top priority for us.”

The conventional wisdom coming out of the speech was that Obama had made a 180-degree shift in his space policy. The Sentinel called it a “dramatic reversal” while Florida Today acknowledged that Obama had “changed an earlier position”. The campaign of his opponent in the general election, Republican John McCain, seized on the apparent reversal in a statement of its own. “Barack Obama once again demonstrated that his words really don't matter,” the statement read. Regarding delaying Constellation, “that is what he proposed and has been saying for months.”

But is that really the case? Did Obama have a sudden change of heart regarding Constellation in particular and space policy in general, which he chose to reveal in Florida this month? A closer look at the records suggests something else: a much earlier, and more gradual, shift in policy by the Obama campaign, which arguably started backtracking from the initial plan to delay Constellation as little as a month after the release of the white paper. The Titusville speech, then, became an opportunity to reconcile the inconsistencies in the campaign’s statements on the issue, although his statements still leave plenty of unanswered questions about what a President Obama would do in the realm of civil space.

Anatomy of a policy change

The Obama statement that first created angst in the space policy community was tucked away at the end of a white paper on education policy released last November. “The early education plan will be paid for by delaying the NASA Constellation Program for five years,” among other ways, the statement read. This was widely interpreted to mean that Obama would freeze all Constellation-related work, including the Ares 1 launch vehicle and Orion spacecraft, for five years, which, in turn, would appear to extend the post-shuttle gap beyond the five years currently projected. McCain alluded to that in a statement he issued on July 29th, the 50th anniversary of the enactment of the National Aeronautics and Space Act, the legislation that created NASA: “While my opponent seems content to retreat from American exploration of space for a decade, I am not.”

However, by late December, about a month after the release of the education policy, some Obama campaign officials were putting a different spin on that claim. “Obama believes we should continue developing the next generation of space vehicles, and complete the international space station,” Linda Ellman, the campaign’s policy director in New Hampshire, said in a email to a resident there shortly before the state held its first-in-the-nation primaries. “While Obama would delay plans to return to moon and push on to mars, Obama would continue unmanned missions,” she added.

| “Obama believes we should continue developing the next generation of space vehicles, and complete the international space station,” an Obama official said in an email in late December, a month after the original campaign statement about Constellation. |

A quasi-official space policy statement from the Obama campaign in January (which appeared on campaign letterhead but was never formally released nor published on the campaign’s web site) made that point clearer, while also addressing the shuttle-Constellation gap. “The retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2010 will leave the United States without manned spaceflight capability until the introduction of the Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV) carried by the Ares I Launch Vehicle,” the statement read. “As president, Obama will support the development of this vital new platform to ensure that the United States’ reliance on foreign space capabilities is limited to the minimum possible time period.” This was in direct contradiction with the November statement, since Ares 1 and Orion are the initial major programs of Constellation, a conflict that puzzled many space advocates.

Obama’s Titusville speech this month also wasn’t the first time that he spoke out on the issue in Florida. Speaking at a town hall meeting in central Florida in May, Obama said he would continue to fund the development of Orion, among other NASA programs, if elected president. “Other countries are in position to leapfrog us if we don't continue to make this investment,” Florida Today quoted him as saying.

The change in position attracted the attention, and support, of Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL), a major supporter of NASA in Congress. “You will see he made a different statement, and I thanked him for that this morning, and he said, ‘I’ve been listening to you,’” Nelson recounted at a Washington Space Business Roundtable luncheon speech on May 22.

Inspiration and commission

While most of the media attention about Obama’s space policy comments in Titusville were limited to his apparent reversal on Constellation, it was not the only statement he made on the topic there. During his prepared remarks, he devoted three paragraphs to NASA, talking about concrete issues, like supporting Constellation and closing the gap between Shuttle and Constellation, as well as some more abstract topics, like inspiration. “When I was growing up, NASA inspired the world with achievements we are still proud of. Today, we have an administration that has set ambitious goals for NASA without giving NASA the support it needs to reach them,” he said.

This theme of inspiration, or lack thereof, is not new to the Obama campaign. On several occasions on the campaign trail this year, Obama has complained that while the agency’s past accomplishments were inspirational—he talked about, as a child, seeing astronauts in Hawaii after returning from Apollo-era missions—the current suite of programs, including the shuttle, lacked that inspiration. “NASA has lost focus and is no longer associated with inspiration,” he said in a Wyoming campaign stop in March (see “Obama’s modest proposal: no hue, no cry?”, The Space Review, April 7, 2008). In April, in a town hall meeting in Indiana, Obama called himself a “big supporter” of the space program but noted that the Apollo program “inspired a whole generation of people to get engaged in math and science in a way that we haven’t – that we need to renew.”

| The proposal to recreate the National Aeronautics and Space Council suggests that the Obama campaign is either listening to the space advocates among its supporters, or is at least thinking along the same lines. |

Later in the response to the same question about the space program, Obama suggested that some kind of review of what NASA was doing was necessary. “I think that we’ve gotta make some big decisions about whether or not, are we going to try to send manned, you know, space launches, or are we better off in terms of what we’re learning sending unmanned probes which oftentimes are cheaper and less dangerous, but yield more information,” he said. “And that's a major debate I’m going to want to convene when I'm president of the United States.” In his central Florida appearance in May, Obama made a similar statement: “I want us to understand what it is we want to accomplish, so we can continue to build this program.”

In his Titusville speech, Obama added some details to that concept of a review of NASA programs. “More broadly, we need a real vision for space exploration. To help formulate this vision, I'll reestablish the National Aeronautics and Space Council so that we can develop a plan to explore the solar system – a plan that involves both human and robotic missions, and enlists both international partners and the private sector.” (see “Senator Obama and re-establishing the National Aeronautics and Space Council”, The Space Review, this issue.)

That particular proposal—invoking the name of the National Aeronautics and Space Council—suggests that the Obama campaign is either listening to the space advocates among its supporters, or is at least thinking along the same lines. In late May a group of Obama supporters met during the International Space Development Conference in Washington to talk about space policy and the campaign. One idea that got virtually universal acceptance was the idea of proposing to re-establish the National Space Council (as it was known the last time it existed, during the administration of President George H.W. Bush) as a mechanism for carrying out a review of the national space efforts.

Unanswered issues

While Obama’s speech went a long way towards clarifying his position on space policy, there are still plenty of questions about what he would do as president, including some questions created by the speech itself. For example, Obama pledged to “help close the gap” between the shuttle program and Constellation by “speeding the development of the Shuttle’s successor”, but didn’t say how he would do it, and by how much he would close the gap.

Tied into that is the future of the shuttle program. Obama said in Titusville that he would work with Senator Nelson for “at least one additional Space Shuttle flight beyond 2010”; as with the statement about closing the gap, he didn’t offer any details, including whether this would be a shuttle flight for launching the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a priority for many in Congress, or a mission or missions on top of that. Obama also claimed that he would make sure “all those who work in the space industry in Florida do not lose their jobs when the Shuttle is retired”, a potentially expensive proposition given the current plans call for laying off at least 3,000 KSC workers once the shuttle is retired.

| Glenn, cited as one of Obama’s space policy advisors, called the Vision for Space Exploration an “unfunded mandate” in a House hearing last month. |

Asked about budget figures by Florida Today after his speech, Obama said he would not commit to adding $2 billion to NASA’s budget (although the report was vague about whether this was a one-time increase, as some in Congress have sought in the last couple of years, or a permanent increase in NASA’s annual budget). He also declined to say whether he would change any long-term aspects of the Vision for Space Exploration, including plans to return humans to the Moon or mount human missions to Mars.

However, the same article reported that Obama said he would rely on both Nelson and former senator and astronaut John Glenn to help form his space policy. The inclusion of Glenn is interesting, given testimony he provided earlier that week to the House Science and Technology Committee during a hearing commemorating the 50th anniversary of NASA. Glenn said that while he was originally supportive of the Vision, he now considered it an “unfunded mandate” since the Bush Administration had not backed up the plan with sufficient budgets. He suggested that more money and effort be put into utilizing the ISS.

While many questions remain unanswered, Obama has at the very least eliminated the apparent contradiction between the statement in his education policy paper and more recent statements by the campaign—to the relief, no doubt, of many space advocates. There will be opportunities between now and November 4 to try and flesh out those details (including a debate Thursday evening at the Mars Society Convention in Boulder, Colorado; Lori Garver will represent the Obama campaign and former Apollo astronaut Walt Cunningham will represent the McCain campaign). However, it’s quite likely that many of those questions won’t be answered until—and unless—Obama wins the election.