Contract protests: a growing cancer on the space industryby Taylor Dinerman

|

| Contract protests are slowly but surely wrecking the defense industry, turing it from an collection of firms whose purpose was to build hardware into a giant jobs program for contract lawyers, litigators, and lobbyists. |

As Dan Quayle once said, “There’s something wrong with an economy that employs 70 percent of the world’s lawyers.” Our government procurement system is so big and so complex that, for a program such as CRS, not to mention a larger one, any competent team of lawyers can find flaws in the tens of thousands of documents, emails, and other evidence. It now seems that once a contract has been awarded its fulfillment relies on the goodwill or a calculated decision by the loser not to contest. This effective veto power will eventually strangle the entire system and force through a set of reforms—possibly on an emergency basis—and the results will not be pretty.

A typical example of this from the non-space world is the Combat Search and Rescue (CSAR) helicopter saga. In November 2006 a firestorm was set off when the Air Force picked the Boeing Chinook (HH-47) as the basis for the next generation of CSAR helicopters, replacing the Sikorsky Blackhawk (HH-60). The main reason, or so we were given to understand, was the ability of the Chinook to operate at high altitudes in places like Afghanistan. That’s a seemingly sensible requirement, but somewhere along the line the Air Force failed to file enough paperwork of the right kind and also did not make an effective case to Congress. As a result, the program is now in limbo while the old Blackhawks have to undergo an expensive refurbishment to keep them flying until a replacement is eventually found.

There are lots of other examples, notably the KC-X tanker contract. The problem extends throughout the government: it will be interesting to see which parts of the stimulus bill now moving through Congress will still be under litigation when the 2012 election rolls around.

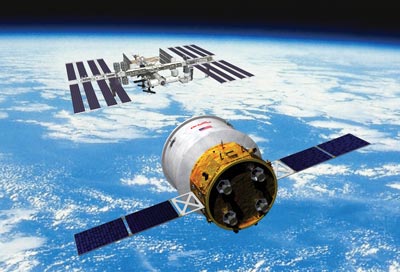

While the aviation sector may be healthy enough to withstand the harm caused to the industry by the protest litigation explosion, the space industry is not in anywhere near as good condition. If protests such as the one from PlanetSpace, or the ones surrounding the BASIC contract, continue, the US space industry will shrink and America will become dangerously dependent on foreign sources for its essential space assets.

Competing on the basis of product quality and price helps raise the level of the space industry for everyone; competing on the basis of who has the most lawyers drags all the players into the ditch. At their best lawyers are enablers, bringing skill sets to companies that allow them to maximize their effectiveness with both the law and societal norms. Unfortunately, when they completely dominate a company or an industry they stifle creativity and cripple the drive to excel.

As more and more attention is paid to fighting and preparing to fight these legal battles, the emphasis on original, high quality products may be lost. In the highly competitive international space and aviation industries these protests will be at least as damaging to America as the ITAR (International Trade in Arms) regulations have been. In a time of economic trouble we cannot afford any more self-generated friction.

| Protests may be deadly to the prospects of the NewSpace industry, but in the medium and long term they will eviscerate the big aerospace firms as well. |

The first level of the protest process is to appeal to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), formerly the General Accounting Office. This alone should set off alarms. The GAO has a terrible record evaluating technology. In the 1980s their reports on the military systems involved in the Reagan buildup were supposed to show that items such as the M-1 tank and the B-1 bomber would fall apart at the first shot in a real war. Indeed, US military hardware was supposedly so “baroque” that if the GAO had been right Saddam Hussein would not only have easily won the 1991 Gulf War, but would probably now be occupying Des Moines, Iowa.

As long as the number of major aerospace contacts are few and far between and as long as the government lacks the will or the vision to preserve intellectual capacity—that is to say the design teams that are the core of the “industrial base”—these protests will continue. They may be deadly to the prospects of the NewSpace industry, but in the medium and long term they will eviscerate the big aerospace firms as well.

Handing over near total control of the industry to the lawyers and sequestering the engineers, managers, and scientists in a penalty box is a recipe for oblivion. GM and Chrysler went down that road and if they don’t watch out, Boeing and Lockheed Martin could end up in the same hole.