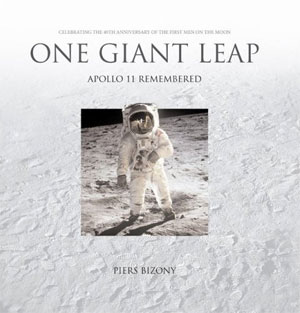

Review: One Giant Leapby Jeff Foust

|

| “Many shots, and especially those taken inside the spacecraft,” Bizony writes, “are blurry, under-exposed, or so random in the choice of subject matter that they can only have resulted from the shutter button being pressed by accident.” |

As a result, only a handful of images taken by the Apollo 11 have been used in books and other accounts of the mission. That’s not the case in One Giant Leap, which Bizony claims to have more images from the mission than any other “mass-market publication”. And, as he warned, some of dozens of pictures in the book are blurry or poorly composed. Yet the images are fascinating and remarkable nonetheless: those technical imperfections make them all the more vivid and real, a reminder that they are documentation by astronauts who were only secondarily—at best—photographers.

Those images make up half of One Giant Leap. The other half is a series of essays about Apollo 11, the broader Space Race that culminated with the historic mission, and a look to the future and the planned return to the Moon by NASA. Much of these cover familiar ground, and in some cases constitute something of a defense of the mission. While the Apollo spacecraft may look old and crude by modern standards (or the expectations of popular science fiction), “Apollo was futuristic and then some” for its time, Bizony argues. “By the standards of the 1960s this was the most advanced machine in history.”

Elsewhere in the book, he compares the effort to send humans to the Moon 40 years ago to the medieval construction of cathedrals: an analogy he admits is clichéd, but one with some element of truth to it. Both cathedrals and spacecraft pressed the limits of technology, and both were the products of large-scale projects. They are also achievements that have been revered long after they were completed. That reverence is on full display in One Giant Leap, and perhaps justifiably so. It’s the images here, though, that remind us that while Apollo featured the development of new rockets, new spacecraft, and new ways of managing such a massive effort, it was ultimately a very human venture.